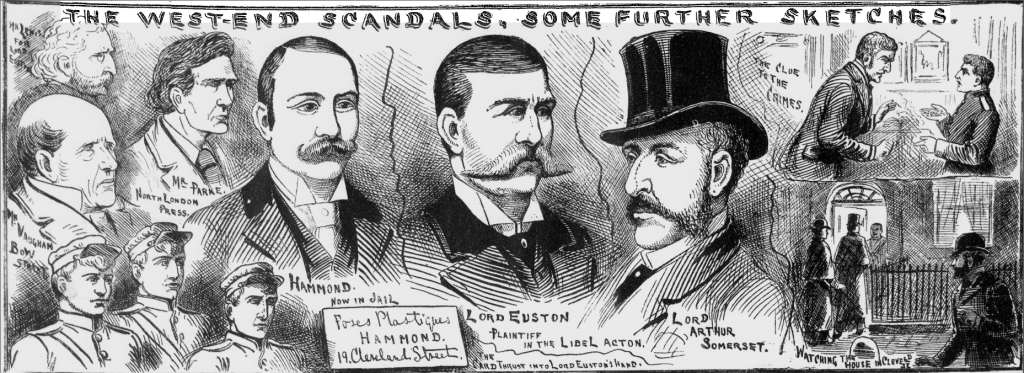

In the summer of 1889 a 15-year-old London telegraph boy named Charles Swinscow had a monumental encounter with his inspector. Charles had eighteen shillings in his pockets, more than twice his weekly salary. Postal Constable Luke Hanks, after discovering this suspicious amount, extracted a statement from Charles that would eventually lead to three different trials, the imprisonment of four men (two for gross indecency, one for libel, and one for obstruction of justice), the lifelong exile of a noted aristocrat, and an international manhunt for a pimp. Charles, a messenger who delivered telegrams between departments at London’s Central Telegraph Office, St Martins Le Grand, had revealed the existence of a house of assignation at 19 Cleveland Street in Fitzrovia, which offered, among other services, sexual encounters between elite men and telegraph boys.

The subsequent paper trail left by Cleveland Street’s exposure intrigued pioneering historians of the 1970s out to uncover homosexual lives and cultures. Since then, scholars have tended to focus on the elite men who patronized Cleveland Street and on the byzantine twists and turns of the related legal proceedings. The Cleveland Street Scandal also fueled months of sensational headlines and illustrations in London’s tabloid press and has consequently been studied as an example of the era’s journalistic innovations. These days Cleveland Street is a relatively well-known late-Victorian scandal, a prequel to Oscar Wilde’s own disastrous encounters with the law six years later. Cleveland Street has even re-emerged as a London Musical, and there’s an online forum thread devoted to pinning down the former building’s exact location.

Cleveland Street is an acknowledged milestone of London’s sexual past, but it has broader significance to historical developments of the late nineteenth century: what has thus far been missing from discussions about the scandal’s notoriety is that it is as much a revelation about new clandestine information monitoring practices as it is of London’s subcultures. The Cleveland Street Scandal is not only a classic Victorian queer sex scandal; it was the first widely-publicized manifestation of a large, well-coordinated and well-funded postal surveillance system that came into being precisely because of telegraph boys’ prior involvement in London’s pederastic prostitution networks.

Previously, in 1877, an internal post office investigation revealed widespread prostitution among its young messengers. The Post Office (then known as the General Post Office or GPO) immediately increased its numbers of uniformed and plainclothes investigators, and over the course of the following year added clerks and inspectors to the small GPO policing department known as the “Missing Letter Branch,” bringing its total staff to twenty. In 1883, it was renamed the Confidential Enquiry Branch. The expansive new name coincided with burgeoning numbers of clerks and inspectors. By 1889, the Confidential Enquiry Branch had over eighty staff members, including fifteen plainclothes detectives and numerous uniformed constables, including PC Luke Hanks. The expansion of other GPO services and the Fenian bombing campaigns in the 1880s also fueled the growth of postal policing. Throughout, telegraph boys’ associations with urban underworlds remained a focus and concern of the increasingly vigilant GPO.

It was post office police who uncovered the Cleveland Street prostitution network, who monitored the comings and goings of the telegraph boys, and who ensured that Charles Swinscow and his fellow telegraph/rent boys did not succumb to their former sexual client’s bribes and abscond to Australia. The Head of the GPO Confidential Enquiry Branch chased the brothel’s proprietor Charles Hammond across France and Belgium, eventually tracing him to Seattle, Washington. By distinguishing the GPO police from the metropolitan police and other security forces involved to various degrees in the Cleveland Street investigation, we can discern a sophisticated network of GPO administrators, constables, and undercover agents that had barely existed a decade before the scandal erupted. This recently expanded and empowered postal monitoring network exposed the brothel and its patrons.

Aristocratic privileges vied against bureaucratic interests in the newspapers and the legal proceedings swirling around 19 Cleveland Street, but it was the latter’s new powers which brought the brothel’s existence to light and shaped the outcome of the scandal. Much of its moral furor was directed at Cleveland Street’s elite patrons: they had corrupted innocents, and aspiring civil servants to boot. The telegraph boys received very little public or legal censure. Those involved were fired from the post office, but they were not arrested or imprisoned for gross indecency.

Postal telegraph administrators at St Martins le Grand, though relieved that Cleveland Street’s revelations did little damage to their institution’s reputation in the eyes of the public, were not so forgiving of their young working-class employees’ involvement in clandestine homoerotic networks and markets. They were well aware of what the press had downplayed: that Charles and three of his fellow telegraph boys had been recruited by a former telegraph boy who had been promoted to clerk (a very rare occurrence only offered to exemplary messengers). This procurer, the aptly named Henry Newlove, had enticed Charles and other messengers with clandestine hook-ups in the basement toilets of the Central Telegraph Office, afterwards revealing that there was money to be made by committing the same acts with wealthy men at 19 Cleveland Street. Where the press saw innocents corrupted, the post office saw the manifestation of a longstanding problem inherent to its London telegram delivery staff. It was yet more justification for the expansion of internal policing powers at the GPO, and in the years that followed the scandal political dissidents, sexual entrepreneurs, and indiscreet aristocrats would join post office employees as often unknowing targets of surveillance and censorship.

Cleveland Street’s revelations coincided with a decade of renegotiations about the role government played in the monitoring of public and private spaces and communications. The post office, that seemingly benign juggernaut, had a crucial role to play in this development. In one sense the discovery of the brothel and the exposure of its clientele was a victory of the vigilant bureaucratic state working for the “public good” over elite privilege built out of subcultures, silences, and discretion. It is a milestone of the British state’s quiet renegotiation of acceptable barriers between public interest and private transactions. By looking at the Cleveland Street Scandal from the perspective of telegraph boys and GPO administrators, it is clear that the history of sexuality is both applicable and vital to the history of governance, particularly to the development of communications surveillance.

As for the telegraph boys at St Martins le Grand, they faced increased disciplinary measures and continued to work for meagre wages. But they still took advantage of the mobility afforded them by their profession, incorporating the thrills, dangers, and opportunities of city life into their daily routines, getting into trouble, and drawing administrative attention for many decades to come.

Katie Hindmarch-Watson is an Assistant Professor of Modern British History at Colorado State University. She is interested in the entangled histories of work, gender, sexuality, political culture, and urban life. She is currently working on a book titled Dispatches from the Underground: telecommunications workers and the making of an Information Capital, 1870-1916.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com