Interview by Gillian Frank

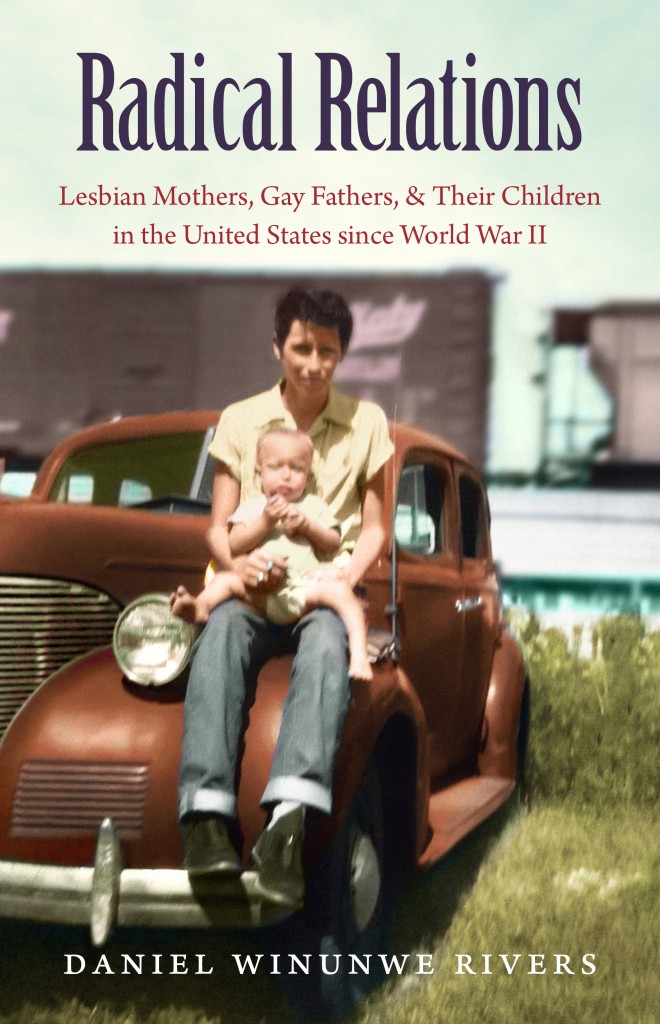

In keeping with Notches’ commitment to fostering a public and widespread discussion of the history of sexuality within and outside of the academy, we are introducing a regular feature that we are calling “Author Interviews.” Here, we publish critical conversations with authors of recent publications on the history of sexuality. Through this feature, we hope to keep you appraised of advances in scholarship, ongoing debates and general discussions on the history of sexuality. For our first author interview, Notches contributing editor Gillian Frank speaks with Daniel Winunwe Rivers, assistant professor of History at Ohio State University, and author of the acclaimed Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers and Their Children in the United States since WWII (University of North Carolina Press, 2013).

Since its publication, Radical Relations was a finalist for the 2014 Lambda Literary Award, LGBT Studies, winner of the 2014 Ohio Academy of History Book Prize and the winner of the 2014 Grace Abbott Prize, Society for the History of Children and Youth. In Radical Relations, Rivers offers a previously untold story of the American family: the first history of lesbian and gay parents and their children in the United States. Rivers argues that by forging new kinds of family and childrearing relations, gay and lesbian parents have successfully challenged legal and cultural definitions of family as heterosexual. These efforts have paved the way for the contemporary focus on family and domestic rights in lesbian and gay political movements.

Gillian Frank: All research projects have a backstory and an autobiographical component. What led you to write Radical Relations?

Daniel Rivers: I grew up in a lesbian feminist community in the San Francisco East Bay in the 1970s. My best friend, Shem, and I were raised in a women’s community that I would describe as lesbian nationalist in its separation from the heterosexual world around us and its critique of patriarchy. We were instructed to be careful who we told about our lesbian families, because of the danger that the state posed to poor, lesbian households like ours. Shem and I were proud to be a part of the struggle against homophobia and to grow up in lesbian communities. We saw our mothers struggle daily with misogyny and anti-lesbian animosity, and we believed them when they warned us about the depth of patriarchal woman-hatred and homophobia in the world around us. I think, though, that we both felt that our lives were without precedent, that we had no history; we felt as if we were at the forefront of a brave new world – that we were the first children to grow up in non-heterosexual households. So, in a sense, the questions that led me to my graduate work at Stanford came directly out of these early moments, together with the awareness that I later developed of the importance of knowing the history of one’s community. Immediately prior to coming to Stanford, I had been doing interdisciplinary graduate work in critical theory. These studies, particularly the work of Michel Foucault, led me to a genealogical framework that opened up questions for me about the intersections of family and sexuality. After beginning this inquiry, I came to believe it would be best pursued through the rigor of social history.

GF: In the book, you beautifully describe how lesbian and gay parents raised children and transformed a culture that deemed them antithetical to families. Your book thus troubles the historically “assumed heterosexuality of the American family” even as you call attention to the oppression, survival strategies, childrearing practices, and activism of lesbian and gay parents. Still, the title of your book insists that lesbian and gay families were by definition “radical.” Could you say more about the title and why the history of lesbian and gay families should be considered radical?

DR: The word radical has two definitions. The first, and the more commonly known, I think, is extreme, revolutionary, or politically progressive. The second, however – and this is the definition I’m working from in the title of my book – is foundational, or of the root or source. A central argument of my book is that one of the foundational notions in American culture is that of the family as by definition heterosexual, along with the inverse idea that queerness is by definition childless. This fundamental notion of the always-already heterosexual family is connected to an even broader tenet of American homophobia that sees children and same-sex relationships as antithetical. This perspective can be seen in anti-gay organizing and thought such as Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign, the 1978 Briggs Initiative, the homophobic assumption of homosexual pedophilia, and the custody cases fought by lesbian mothers and gay fathers. The histories that I trace, as diverse as they were in terms of political styles and the relative importance of activism, all challenged this dominant understanding of the family in the United States. The experiences of lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children ran contrary to the fundamental, root definition of the family as heterosexual. Whether politically avant-garde or assimilationist – and they have been both of these things in different moments across the last six decades – lesbian mothers, gay fathers and their children unsettled this deep assumption and injunction in American society. That is why so many lesbian mothers and gay fathers had their children taken away for decades and why lesbian and gay families with children are even now still so often perceived as something strange or at least novel. It is that genealogy, of the way that family has been defined as and presumed to be heterosexual and how lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children have challenged this definition and presumption, that I meant to capture in the book’s title.

GF: How does your project, which frames lesbian and gay parents and their children as undertaking a radical endeavor, complicate work by queer theorists and historians who might understand the family as a site that is hetero- or homo-normative and potentially depoliticizing?

DR: I think that current criticisms of the LGBT freedom struggle’s push for same-sex marriage and domestic rights as normative should give us all important food for thought. Same-sex marriage, which I support as a pragmatic way to ensure a myriad of rights for parents, immigrants, and persons struggling with disabilities, just to name a tiny fraction of the people who might potentially benefit from the struggle, will also almost certainly intensify the privileging of nuclear families and intimate relationships over non-nuclear ones. Let me give you an example from the history of lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children to illustrate this: in the 1980s and 1990s, as part of what has been dubbed the “lesbian and gay baby boom,” diverse, non-nuclear childrearing arrangements emerged in LGBT communities. These could include a lesbian having a child with her female partner and a gay man, a single lesbian having a child with a gay male couple, or two or more couples collectively raising children. As same-sex marriage codifies an American tradition of legitimizing only monogamous, nuclear intimate relationships between two partners, people in these other kinds of arrangements will find their rights and their families ignored by these changes. In addition, since same-sex marriage will be celebrated as a move toward a more fully inclusive society, these individuals will probably find themselves increasingly devalued by the codification of this definition of inclusion and may feel an increased pressure to conform.

I also believe that the criticisms of same-sex marriage struggles or campaigns for family rights that point to the way that those campaigns tend to portray LGBT families as white, affluent, and lesbian and gay as opposed to bisexual or transgender, are very important; we must be watchful for reductive, assimilationist political moves as our freedom struggle gains strength. However, the history in Radical Relations shows definitively that neither today nor historically has the family had one static character. It has never been monolithically heterosexual, queer, normalizing, nor progressive. The notion that the family is always normative misses the complexity of how the family has operated for the cultural code itself, the injunction that it always be heterosexual and opposed to queerness. Following Foucault, we must instead see the family as a discursively created concept that means many different things – it has been, in fact, a particularly productive site of both regulation and resistance in the United States and, as such, richly rewards our scholarly inquiries into its nature. I am enthusiastic for a new family history that is grounded in questions about how the family has operated as both regulatory regime and an embodied, intergenerational site of resistance to these regimes at the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality.

GF: The book’s seven chapters interweave more than a hundred oral histories with a wealth of archival documents in order to present a national history of lesbian and gay parenthood and activism. Tell us about the process of conducting oral histories. What were the challenges and rewards of finding, selecting and interviewing informants? How did your oral histories confirm, complicate or contradict your written sources and how did you navigate these tensions?

DR: Doing the oral histories for Radical Relations was among the most transformative experiences of my life. It is incredibly humbling to sit with people in their homes and have them share their most painful, intimate memories with you. The first interview I conducted was with Jeanne Jullion, a lesbian mother who fought one of the most famous lesbian mother custody cases of the 1970s, in the San Francisco Bay Area. I’ll never forget how we sat on her couch and she wept as she told me the story of having her children taken from her by a judge because of her love for women. I’ve come to think that all historical sources have their own unique strengths, and oral histories are incredibly powerful for getting at the affective, emotional complexities of the past. In a profound way, sitting with so many people, as they told me stories of their lives across the twentieth century, utterly changed me – it deepened my respect for the complicated richness of human experience and the way we experience sexuality, and it taught me how to listen better and more deeply. Of course, like all sources, oral histories also have their own unique difficulties. I did face issues with participants remembering things in a way that the manuscript sources contradicted. These instances usually had to do with dates or the specifics of the history of a certain group, which because organizations are made up of many people, are not always accurately reflected in the memories of one individual.

To deal with this, I made sure to corroborate details with multiple manuscript sources whenever possible. Finding participants is always a challenge – I drove all over the country, eager to sit with anyone who said yes to doing an interview. I do remember one woman who, whenever I contacted her, repeatedly expressed her willingness to talk with me but never seemed to have the time. She had gone through one of the most brutal lesbian mother custody cases in the state of New York, and eventually I realized that it was just too painful for her to go back through the experience of having her children taken away from her. After two years I stopped trying to set an interview up, seeing that sometimes ethics demand hearing beyond what is spoken.

GF: How do you see Radical Relations being used in the classroom and what range of courses might it be used in? What other book(s) would you assign to accompany Radical Relations?

DR: I see Radical Relations as part of a new history of sexuality that looks at the ways citizenship is mediated through categories of race, class, gender, and sexuality. I just taught a graduate course on the history of sexuality in the United States from the colonial era to the present and I taught my book in conjunction with Pablo Mitchell’s Coyote Nation, Margot Canaday’s The Straight State, and Elizabeth Pleck’s Not Just Roommates: Cohabitation after the Sexual Revolution. This combination of books worked well to give the graduate students a sense of new directions in the history of sexuality, as well as an understanding of how various scholars are conceiving of systems of regulation and resistance that have operated through gender, sexuality, race, and class. I think the book also works well as a text in an upper-level undergraduate or graduate class on the U.S. postwar history of sexuality, race, and the family, alongside work by scholars such as Rickie Solinger. And finally, it could be used in a course on modern LGBT history or a US history survey course with a significant component that dealt with sexual minority communities and/or the history of family and sexuality.

GF: The first two chapters of Radical Relations focus on the pre-Gay Liberation era and trace the experiences of “gay men” and “lesbians” who had children within heterosexual marriages. The chapters also call attention to the complexity of the institution of marriage by showing how many men and women did not “come out” of heterosexual marriages because they feared that their children would be taken away from them. Could you say more about your choice to describe these men and women as “gay” and “lesbian”? Are these terms shorthand or were these the ways in which these historical actors understood themselves?

DR: One of the challenges of doing histories of sexual and gender minority populations before the liberation era is the care we must take not to import our modern notions of sexual and gender identity into the historical narrative and erase more complex ways of being. So, for instance, in Radical Relations, I use terms like “gay” or lesbian” to describe individuals who were heterosexually married and had same-sex relationships clandestinely. This was an important part of the history of lesbian mothers and gay fathers, since the widespread cultural homophobia of the era often forced people to live double lives if they wanted to have a career or raise children. For the most part, the sources I used indicated a gay or lesbian identity – for instance a letter written into a homophile periodical celebrating the nascent civil rights movement or describing a longtime relationship with another married man in which the writer seemed to clearly indicate that this was their primary relationship and that their primary attraction was to other people of the same sex. It was also the case that many of these people did, in fact, refer to themselves as gay or lesbian.

Another abundant example of this kind of clear identification is in the large number of oral histories done by historians and preserved in LGBT archives. The parents I found through these records and whose stories I incorporated did identify themselves as gay and lesbian. Nonetheless, it was still important that I be careful not to erase bisexual history through an assumption of gay and lesbian identities. This was something I tried to do at every turn, but in the end, it is still the case that the documentary historical record itself may have codified some of this kind of erasure – as in the case of arrest records or other fragmentary evidence. When I conducted oral histories, however, especially in cases where participants spoke about their relationships with heterosexual spouses as ones that were fulfilling to them, I made sure to ask them whether they identified as gay or bi parents and then wrote about them accordingly. There is only one instance in the book, the case of A. Billy S. Jones, who identified early in his political career as a gay man but later came out as a bi activist, where I would correct the text to reflect that shift if I had the chance. In spite of the care I tried to take not to erase bisexual identified people’s experience, Radical Relations still remains the history of lesbian and gay parents, rather than queer parents or lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender parents. I initially intended to focus my doctoral work on the history of LGBT parents and their children, but the realities of what was possible and the specificity of bi and trans history eventually led me to limit my book to a history of lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children.

A history of bi and trans parents and their children would need to include a number of organizational and cultural contexts and histories that are not included in the book. These are very important histories, and I hope Radical Relations will serve as inspiration for them. Bisexual history is still a very new field, with room for many scholars to pursue a number of lines of inquiry, and the history of trans parents will be both similar and different from the history of lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children, as cisgender prejudice and trans activism has fundamentally shaped that history.

GF: Most of the gay and lesbian parents you interviewed came out of heterosexual marriages. Much of the book frames coming out of marriages as a liberating experience and the chapters follow a narrative arc that moves from repression to liberation. I’m curious to know if the issue of loss or regret about leaving heterosexual marriages came up in your interviews. Did men or women who had left their marriages and/or come out as gay or lesbian over the course of their lives ever regret their choices? Beyond the obvious heterosexual privileges, did any of the people you spoke with feel sad about choices they had made?

DR: That is an interesting question. I wouldn’t say loss or regret about the end of a marriage exactly, but in the case of some of the older gay men who had lived double lives in the 1950s, there was often a complex relationship to these earlier relationships. Men who had not told their spouses that they loved men and engaged in clandestine same-sex sexual relationships often expressed sadness at having misled their ex-wives. They also sometimes needed to say that they had experienced fulfilling and vital sexual and emotional relationships with their spouses. I would then ask at this point if they identified as “bisexual” or “gay” fathers, and they said that they identified as gay fathers. I think this points back to the complexity of sexual histories – people’s lives and intimate experiences do not always fit into our contemporary notions of identity and desire. However, my participants definitely expressed a sense of relief and joy in describing their coming out. I think that is an experience that strongly marks this era of LGBT history.

GF: In what ways did unequal economic resources among gay male and female parents affect their relationship to parental politics and the success of those politics? Did this add to tensions between lesbian parental activism and gay parental activism? In what ways did they collaborate most effectively?

DR: Lesbian mother groups and gay father groups were different in many ways, economic resources being one important distinction. This is not to say, however, that all gay fathers were or are economically privileged. It is a common assumption that gay men in general are better off economically than lesbians, but this is connected to the reductive perception that gay men are all white and middle or upper-class. But in regards to the parenting groups, lesbian mother groups emerged from lesbian feminist communities in an era where women who left heterosexual marriages to be a part of these communities were economically disadvantaged and faced sexism when seeking employment. In contrast, although there were some gay fathers organizing in the gay liberation groups of the early 1970s, most gay fathers groups formed a little bit later, in the early 1980s, and were made up of mostly white, middle or upper-class men. These men did have significant economic capital. The truth is that most lesbian mother groups and gay father groups remained separate throughout the 1980s. The change there is really one of different eras of lesbian and gay parenting. It was the families that were increasingly having children through insemination, surrogacy, and adoption that would form groups made up of both lesbian mothers and gay fathers and would begin to work and socialize together. The legacies of lesbian feminism and separate gay fathers groups remained a part of these new groups, but they also developed a fundamentally new character.

GF: In chapter 4, you emphasize how lesbian mothers’ groups focused resources on custody battles whereas chapter 5 reveals how gay fathers were unlikely to have custody or to leave their marriages. Gay men’s support groups, discussed in chapter 5, accordingly helped men develop strategies to maintain relationships with their current and former spouses and their children. In the latter chapter, we glean understanding of the emotional lives of heterosexual women whose husbands came out as gay and the economic and psychological upheaval they faced as a result. We don’t, however, get the same sense of what motivated heterosexual men. How did you recover the voices of the ex-spouses of lesbians and gay men? What are the possibilities and challenges of making their experiences legible and understandable?

DR: Both lesbian mothers and gay fathers fought for custody and visitation rights in the courts, and consequently, when their members were involved in these struggles, both lesbian mother and gay father groups helped them find attorneys, raise funds, and lent them support. However, it is true that members of gay father groups, when not involved in custody battles, tended to stay in contact with their ex-spouses (and even remained married in some cases), whereas members of lesbian mother groups did not. This happened as a result of a complex set of historical factors. Lesbian mother groups were lesbian feminist organizations, and members often saw their ex-husbands as patriarchs who would attack them as strong women. At the same time, gay fathers were men, and often came out in marriages where they had significant economic privilege compared to their spouses. In situations where their wives did not remarry, these women might still be dependent on their ex-husbands for survival and, in any case, gay fathers were not necessarily leaving these relationships behind as part of a political commitment that involved a criticism of their ex-spouses, the way that lesbian mothers who were involved in lesbian feminist communities were. In general, Radical Relations does not focus on the experiences of heterosexual partners of lesbians and gay men in any of the eras that are covered by the book.

Certainly, much more research needs to be done on intimate relationships and kinship formations that cross lines of sexual and gender identity, and hopefully some of this work will address the experiences of these heterosexual partners. However, as you note, there is more discussion in the book of the ex-wives and wives of gay father group members than the ex-husbands of lesbian mothers. This difference was essentially structured by the differences in these relationships discussed above; since the wives and ex-wives of gay fathers were active in these organizations, I felt that their story needed to be a part of my story of these organizations. Of particular importance, Amity Buxton, the ex-wife of a member of San Francisco Bay Area Gay Fathers, has been organizing on behalf of the heterosexual spouses and ex-spouses of gay men and lesbians for thirty years. She founded the Straight Spouse Network in 1986. Her books, The Other Side of the Closet and Unseen-Unheard: The Journey of Straight Spouses would be important starting points for anyone researching this topic.

GF: Over the past decade, images of lesbian mothers, gay fathers and their children have figured prominently in the political struggle for gay marriage and gay civil rights. Children in particular have testified before the courts and in state legislatures and humanized gay and lesbian relationships by portraying their parents as healthy and loving. This activism, on display in recent court and legislative victories, is discussed in your epilogue. The ways in which children of lesbians and gay men acted as “emissaries between their families and the heterosexual world” and helped “create space for their families in a cultural milieu that saw their families as an impossibility” is also a major theme of your book. We wonder if you could say more about the ways in which children were also enculturated into dominant sexual and gender norms. Did gay and lesbian adults in any way reproduce dominant gender and sexual norms in their own childrearing practices? Put another way, did gay parents teach their children how to pass in order to navigate outside of queer social situations? Did children import sexual and gender values that challenged their parents’ values or movement values?

DR: Because lesbian mothers, gay fathers, and their children challenge a fundamental discursive principle in American culture – that the family is by definition heterosexual – their relationships have often been imbued with political meaning for society at large. One of the core homophobic fears that they engender is the concern that the children of lesbian mothers or gay fathers will go on to have same-sex relationships themselves, which is a homophobic concern, because in the instances I am referring to, this is always seen as a bad thing. At times, this has led to pressure on the children of lesbians and gay men to declare their heterosexuality, or risk becoming a symbol of the worst fear of straight America. In 1991, when Dan Cherubin founded Second Generation, a group for LGBT children of LGBT parents, he faced animosity from gay fathers and lesbian mothers who perceived what he was doing as politically dangerously because it confirmed homophobic fears. But he also got support from activists who believed that pandering to these fears was counterproductive. In my research, I have definitely come upon examples of gay and lesbian parents attempting to protect their children by teaching them how to keep the realities of their families a secret from the outside world, but this isn’t exactly the same thing as teaching their children to “pass” in terms of sexuality or gender performance. Truthfully, one of the most interesting things that come to mind for me in response to this question, is the way that generations of children have now grown up in consciously anti-homophobic households that celebrate same-sex intimacy as beautiful and a fundamental civil right. They have also grown up in queer cultures and may define themselves as queer by culture of origin; this should not be surprising, as sexual and gender minorities do make up distinct cultures in the United States with histories going back throughout the twentieth century. Children who grow up primarily in these cultures are in many cases fundamentally a part of them and have distinct values and perspectives when compared to mainstream American culture. These notions — that an anti-homophobic familial environment and generational same-sex sexual orientation can be celebrated, and that one can be queer not based on erotic object-choice but based on culture of origin, are two of the ways that LGBT families with children challenge widely-held ideas of sexuality and gender in the United States.

Daniel Rivers is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History at The Ohio State University. He is a historian of LGBT communities in the twentieth century, Native American history, the family and sexuality, and U.S. social protest movements. His first book, Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since WWII, published by the University of North Carolina Press in September of 2013, won the 2014 Ohio Academy of History book prize and the 2014 Grace Abbott Prize for the best book on the history of childhood and youth. He is currently at work on a second book project entitled, Outsiders Within: LGBT and Two-Spirit Native Americans in the Liberation Era.

Daniel Rivers is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History at The Ohio State University. He is a historian of LGBT communities in the twentieth century, Native American history, the family and sexuality, and U.S. social protest movements. His first book, Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children in the United States since WWII, published by the University of North Carolina Press in September of 2013, won the 2014 Ohio Academy of History book prize and the 2014 Grace Abbott Prize for the best book on the history of childhood and youth. He is currently at work on a second book project entitled, Outsiders Within: LGBT and Two-Spirit Native Americans in the Liberation Era.

Gillian Frank is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion and a lecturer in the Department of Religion at Princeton University. Gillian’s research focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race, childhood and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently revising a book manuscript titled Save Our Children: Sexual Politics and Cultural Conservatism in the United States, 1965-1990. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1

Gillian Frank is a Visiting Fellow at Center for the Study of Religion and a lecturer in the Department of Religion at Princeton University. Gillian’s research focuses on the intersections of sexuality, race, childhood and religion in the twentieth-century United States. He is currently revising a book manuscript titled Save Our Children: Sexual Politics and Cultural Conservatism in the United States, 1965-1990. Gillian tweets from @1gillianfrank1

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Pingback: News and Announcements |

Pingback: What We’ve Been Reading | NOTCHES

Pingback: The migration of same-sex couples to the suburbs is shaping the fight for LGBT equality – Headlines

Pingback: Same-sex suburban couples are changing the equality fight – Uromi Voice