Black inequality—inaugurated under slavery and maintained by protean forms of white supremacy—has been central to American society, through to the present day. But where does AIDS fit into this story?

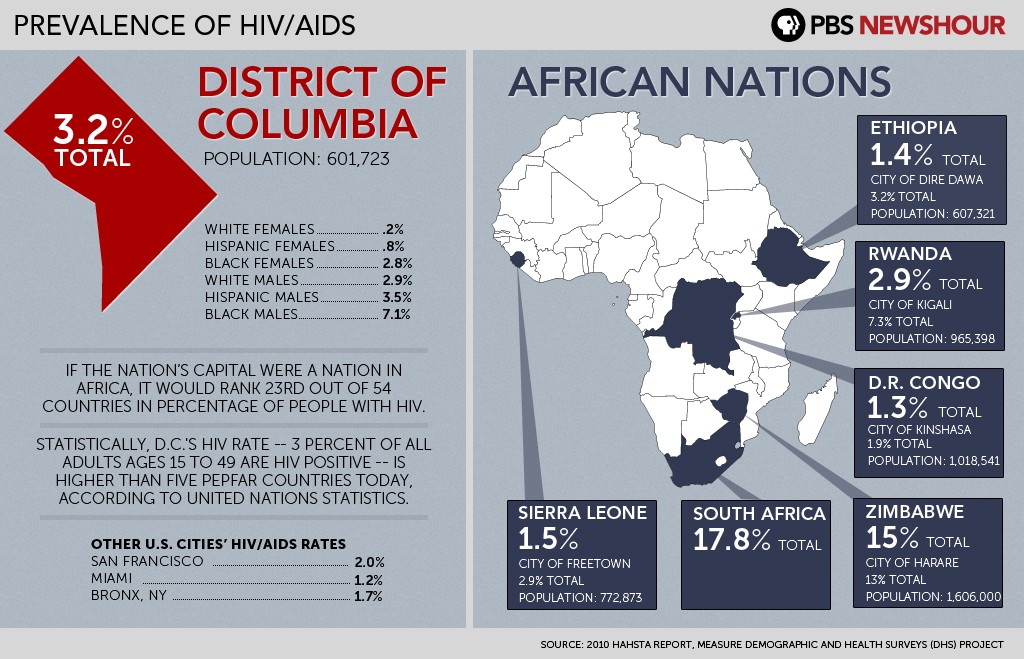

From the beginning of the recognized epidemic in the United States, communities of color—and African Americans in particular—have been disproportionately affected by AIDS. In 1985, four years after U.S. doctors first identified the new disease, African Americans accounted for around a quarter of AIDS diagnoses among adults and adolescents, about double their share of the total population. That disparity has continued throughout the course of the epidemic. In 2010, African Americans made up 44 percent of people living with HIV in the United States, 44 percent of new HIV diagnoses, and almost half of new AIDS diagnoses in 2011, although African Americans make up only around 12 percent of the U.S. population. By the end of 2011, an estimated 265,812 African Americans with AIDS had died in the United States. About twice that number are currently living with HIV. And whereas AIDS among whites has been mostly limited to gay and bisexual men, heterosexual transmission is much more common in African-American communities. In 2010, black women were twenty times more likely to contract HIV than their white counterparts. In sum, AIDS has devastated black America.

With this in mind, much historical research remains to be done on AIDS history in black communities. My own work focuses on African-American AIDS activism, and the ways that black communities organized grassroots AIDS education and prevention programs. Without an understanding of this history, black communities appear as passive, powerless victims of the epidemic, or as prejudiced people who failed to take “ownership” of a disease associated with gay men and drug users.

One key strategy of African-American AIDS activists has been to highlight the role that segregation, discrimination, and poverty play in exacerbating the AIDS epidemic among black Americans. The impact of AIDS on black communities certainly indexes racial inequities, but historians also need to consider the ways that AIDS has shaped the material reality and lived experience of black people in post-Civil Rights America. AIDS in black America is not only the result of poverty and inequality, but also reinforces racial inequities by constraining black opportunity. We might measure the impact of AIDS on black communities in terms of the work hours lost to opportunistic infections and caring for the sick, or in the sheer expense of treatment and hospitalization. Moreover, the psychological stress that AIDS places on loved ones and caretakers likely generates a ripple effect of other expensive health problems. Current research points to a link between trauma (particularly in childhood as with, say, the loss of a parent to AIDS) and chronic illness later in life. In this way, AIDS magnifies inequality by exacerbating the very inequities that render black communities particularly vulnerable in the first place.

Another index of the impact of the disease in black communities is the cost of caring for the ill. A 2006 study found the lifetime cost of HIV treatment in the United States to be around half a million dollars. That figure, multiplied by the half a million African Americans currently living with HIV, yields a total lifetime cost of treatment for AIDS in black America on the order of $250 billion. Even with the uneven expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, people with AIDS remain in a situation of permanent precarity. Notably, the Southern states that have rejected Medicaid expansion are those with black communities particularly affected by AIDS. The high cost of HIV treatment, combined with poverty, helps account for the fact that African Americans progress from HIV infection to AIDS diagnosis and then death more quickly than both whites and Hispanics.

AIDS has likely worked in other ways to constrain black opportunity, particularly around housing and mass incarceration. Sarah Schulman argues that the onset of AIDS in the 1980s accelerated gentrification in Manhattan. As gay men died in droves, their apartments turned over to market rental rate. In short order, the deceased were replaced by the relatively privileged, whose tastes remade the East and West Villages into the playgrounds of capital that they are today. But gentrification does not only bring displacement of racially and economically diverse communities. African Americans in gentrifying neighborhoods become ensnared in the criminal justice system through the “quality of life” policing that makes neighborhoods palatable to new, affluent, white residents. In turn, both incarceration and the lack of available affordable housing are linked to the spread of HIV in black communities.

If Schulman is correct, then AIDS has not only killed hundreds of thousands of African Americans, but has also redrawn the landscape of American cities so as to concentrate HIV in black communities. An argument as provocative as this one deserves to be validated—or complicated—by quantitative analysis. Can we correlate the epidemiology of HIV in American cities to historical data about rising rents and racial displacement? On this point, a large-scale digital mapping project, similar to the one that AIDSVu has put together using recent HIV data, could shed light on how AIDS has shaped the recent social history of black America, and of the United States as a whole.

Intertwined ideologies about race and governance have also ensured that African Americans benefit less from the gains made in the fight against AIDS. Although the availability of antiretroviral drugs beginning in the middle 1990s transformed HIV into a chronic manageable illness, the expense of those drugs meant that not everyone would benefit from the pharmaceutical innovation. The high price of drugs has been maintained by bipartisan support for intellectual property protections and free trade policies. These policies, pursued by Democrats and Republicans alike, have curtailed the possibility of treating the epidemic with inexpensive generics instead of expensive name-brand drugs. At the same time, the antipathy to government programs—especially but not only in the Deep South—such as the Affordable Care Act limits the amount of medical relief available to black communities struggling with AIDS. The disease thus manifests the violence of white supremacy and structural racism on black bodies.

There is a historical precedent for the thwarting of black freedom by epidemiological disaster. Historian Jim Downs has shown that the emancipation of millions of southern slaves after the Civil War was accompanied by a rash of diseases that killed tens of thousands and thwarted the promise of freedom. Here, deeply entrenched beliefs about racial hierarchy underwrote an indifference to the suffering of freed people. This racial ideology also fueled grassroots efforts among Southern whites to strip black men of the right to vote, and a waning enthusiasm among Republicans for using federal power to pursue racial equality. In the end, post-Civil War Reconstruction failed as white supremacy kept former slaves out of both polling places and hospital beds.

Similarly, over the past thirty-five years, AIDS has manifested and maintained racial hierarchy in American society. Through suffering and death, the epidemic in black America arises from and reinforces both structural racism and deep-seated ideologies of white supremacy. Historians of the United States—but historians of the African-American experience in particular, no less than historians of gay life—need to consider how stories about the recent past change when we put AIDS at the center. What does the epidemic mean for histories of black labor, as illness left many too sick to work? Some have noted the leadership of queer youth at the head of the Black Lives Matter movement; what does it mean for the history of black protest politics that AIDS has killed an outsized number of black gay men, across several generations? How does the last forty years of American urban history look different when we put the impact of the epidemic on black communities at the center of the story? And particularly for readers of this blog, what does AIDS mean for histories of love, sexuality, and courtship in black communities? Without a better accounting of this devastation, our histories of the recent African-American past will remain entirely incomplete.

Further reading:

Cathy Cohen, The Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics (Chicago, 1999).

Adam Geary, Antiblack Racism and the AIDS Epidemic: State Intimacies (Palgrave, 2014).

Dan Royles is a visiting assistant professor of history at Richard Stockton College of New Jersey. His research focuses on the politics of the body and social movements in recent American history. He is currently working on a book manuscript, oral history project, and digital archive dealing with the political culture of African American AIDS activism. Follow him on Twitter @danroyles.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Great article.

Good news, DC’s HIV rate is now 2.1%. Bad news, DC’s AA infection rate is 5.7%. Bad news, still exceeds WHO’s epidemic definition…

http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/city-officials-fewer-new-hiv-cases-in-dc-in-2012-but-infection-rate-still-epidemic/2014/07/02/cbce2be4-01f0-11e4-b8ff-89afd3fad6bd_story.html

keep up the good work.

Thanks for the link and the comment! Sadly, Washington DC has a high HIV prevalence (especially among African Americans) in common with a lot of other Southern cities. One thing that seems to be different is that in Southern states like Louisiana or Mississippi, we can point to a purposeful disinvestment from public services by Republican-dominated state governments to explain some of this. The case in Washington, DC may be different—it’s much more liberal, but I admit I’m not sure how their public funding works. I would guess that they’re eligible for Ryan White funds in the same way that states are, but I’m honestly not sure of that. Keep an eye out for Kwame Holmes’ forthcoming work—it deals in part with AIDS and black gay men in the District, and it’s sure to be very, very good.

Reblogged this on African American AIDS Activism Oral History Project and commented:

Considering the impact of the AIDS epidemic on African-American history.