Interview by Marc Stein

In May 1988, when I was working as the coordinating editor of Gay Community News in Boston, Massachusetts, I interviewed Jeffrey Weeks, the influential British sociologist and historian who had written Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present (1977), Sex, Politics, and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality Since 1800 (1981), and Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths, and Modern Sexualities (1985). The interview took place in Boston and edited excerpts were published in the 30 October 1988 issue of Gay Community News (pages 8-9). What follows is the complete transcript, with minor changes recommended by Weeks in 1988 and 2014 (the latter indicated with brackets) and minor editorial corrections. Weeks later published many more books and articles on the history and sociology of sexuality. He is now Emeritus Professor of Sociology at London South Bank University. His most recent books are The Languages of Sexuality (2011) and a fully revised 3rd edition of Sex, Politics and Society (2012). He is currently working on a book entitled What Is Sexual History? to be published by Polity Press in 2015/16.

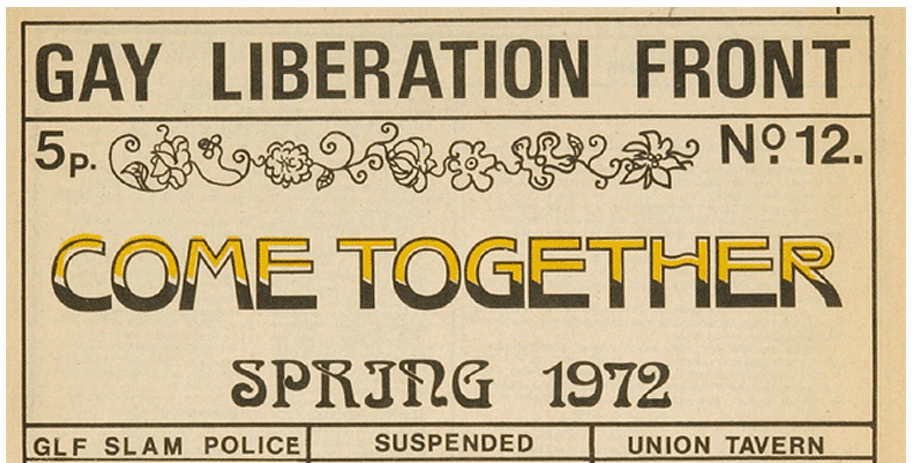

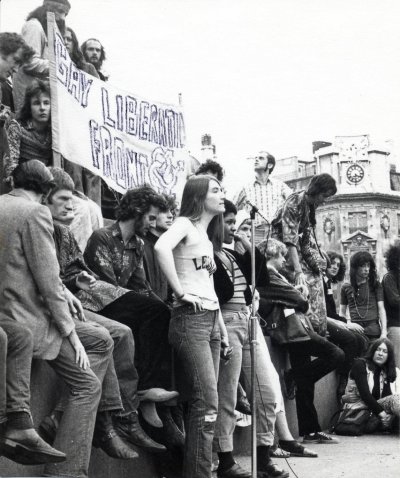

Marc Stein: I thought we would first talk about the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), then talk about your views on the differences and similarities between the U.S. and the British lesbian/gay movement, then talk about your role in the emergence hypothesis, and then finish up with AIDS. My first question is about the Gay Liberation Front, which I understand formally existed in Britain from 1970 to 1972. In Coming Out, you describe yourself as a participant in the GLF and as a historian of the movement.

Jeffrey Weeks: Yes, I got involved in British gay liberation in 1970, a coincidence of several events really. One was a sense of personal crisis in my own life, in my emotional involvements. Although I had been actively gay for about five years, it was very much a sort of individualized gay life, with one or two gay friends. No involvement in a subculture or anything like that. I had just had a relationship which came to an end and was feeling rather isolated. Another element was that in 1970 I started work at the London School of Economics (LSE) at the very moment when the GLF started meeting there in October 1970. Two students who had been over here and had been inspired by the American GLF came back and just called a meeting. So I missed the first couple of meetings but went to the third and fourth. The third factor was that for some time I had been on the left politically but felt acutely displaced from mainstream leftism. This is not just retrospective; it is what I felt at the time. I felt that because I was a gay person there was no way that I could integrate into that sort of politics.

What gay liberation offered at the beginning was a sense of the bringing together of the various strands of my life: the personal need, the fact that I was working there, and a wider political framework. The three came together very explosively in my own life and in the life of many other people. And it also transformed my personal life immediately. Within the first couple of weeks I met the person who was to become my lover for the next ten years and I met most of the close friends I am still close to. It brought together the political, personal, social, and career in an immediately explosive culmination. And there’s been no looking back since then. In one way or another, I’ve been involved in lesbian and gay politics ever since, in the beginning working in activist groups and then increasingly in gay journalism and subsequently in gay history and then broadening out into the history of sexuality more generally. I’ve been marked by that experience. It’s still in many ways the mainspring of my social and political activity.

MS: I wonder if that will come to be true of me as well. I got involved with organizing the 1987 March on Washington in New England. And it has transformed my life. My personal life and political work have been radically changed.

JW: Edmund White’s latest novel [The Beautiful Room is Empty] ends with Stonewall. The last lines of the novel refer to this as “the turning point of our lives.” And that’s absolutely true for hundreds and thousands of us. It’s certainly true for me. But it was not so much Stonewall as the events a year later in London, which echoed the emergence of gay liberation over here, that spoke to me. I draw a more general experience from this. My experience in gay politics transformed my life. But I think it’s a more general phenomenon that’s happening. Involvement in similar movements—that is, the women’s movement, the black movement, the peace movement in the U.S. and Britain—has a similar effect on people, a transformative effect. And that tells us something very profound about what’s happening in the politics of the West in the last twenty years. Increasingly people come to radical politics not through any abstract acceptance of theory learned in the classroom or from traditional modes of mobilization like class. Class still exists, but because of the vast changes in industry, technology, and social structure that are shifting all our lives, class identities are no longer fixed or unchanging. Increasingly people are moved into politics from a sense of identification with what seems like local struggles, but in working through them you get a much wider perspective about the nature of social reality in advanced industrial society. So I think our experience twenty years ago is sort of emblematic of an experience increasing numbers of people have been going through in the last twenty years. Politics that is both intimately connected with one’s sense of self but can be generalized into a greater awareness of the way in which social structures and power structures shape identities, shape the space in which we live our lives, and therefore offer an opportunity for challenging those power structures at local points and generalizing them into wider political struggle.

MS: Do you think that sort of identification has replaced another sort of identification?

JW: I put it in a slightly different way. I think that one of the most characteristic features of advanced [industrial] societies in the last generation has been the increasing fluidity of identities and the multiplication of subject positions from which one can view the world. And this is an effect of the most rapid period of social transformation the West has ever seen. The experience of both the right and the left in the last twenty years can be explained by attempts to grasp hold of, understand, or resist in the case of the New Right, this new fluidity of social identifications. All this means that the traditional subject positions—working class, say, which in Britain was a very solid basis for political mobilization—have been fragmented in all sorts of ways over the last twenty years. As far as the left is concerned, this has not been replaced by a single alternative focus of identification, which is why the traditional left parties in Britain are hopelessly split both between one another and within each other. This is why Thatcherism is able to triumph on a minority of public support, which has nonetheless seized hold of a part of the electorate, especially the more affluent and skilled manual working class, that was traditionally Labour-supporting. So there’s a new political geography emerging over the last twenty years, which I think we still don’t fully understand. Most traditional political commentators still talk in the traditional terms of political mobilization and coalition formation. I think the scene has changed absolutely fundamentally. We’re still trying to find our bearings.

MS: So for now we’re really going to see a more divided politics, rather than unifying themes?

JW: Yes and no. One has to hold together both unifying themes, which in Britain can be themes like democracy and social justice and so on, traditional themes which can hold together very diverse social struggles—gay, feminist, black, and so on—while at the same time recognizing the autonomy and separate histories of these different struggles. What one can’t do is subsume these different struggles into one mass force, which would be equivalent to the mass force offered by the working class-led democratic and socialist movements of the immediate postwar years. That is gone forever. One needs to combine unity and diversity, hold it together. I think the reason the left has failed in most western countries is that they are unable to (a) see what the problem is, and (b) maintain this sleight of hand, to hold together disparate forces at the same time as finding universal themes.

MS: Back to the GLF, you’ve written that one of the things that tore apart the GLF was conflicts over feminism. That sounds like what you’re describing here. Has this changed since that time in the liberation movement in Britain?

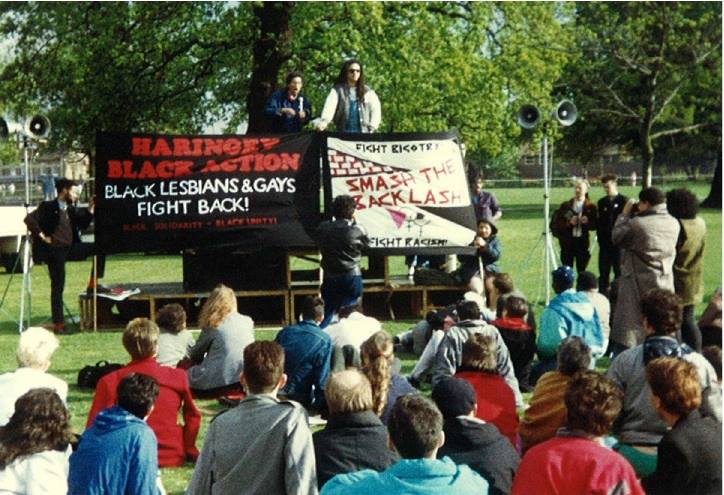

JW: Well relations between men and women in the lesbian and gay movement have waxed and waned over the last eighteen years. We’re now finding a high point of cooperation. The reasons are very instructive. It’s because of the British Government’s attempt to limit what it calls the promotion of homosexuality through Section 28 of the Local Government Act. Essentially, Section 28 is an attempt by the Government to halt the public affirmation of homosexuality. It’s not an attempt, as such, to thrust lesbians and gay men back into the closet. It’s not an attempt to wipe out homosexuality at all. It’s not even an attempt to illegalize homosexuality. What it does do is say that homosexuality cannot ever be seen as a valid alternative to heterosexual family relationships. The key phrase in Section 28 is the one which says that it is intended to prevent the promotion of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship. That’s absolutely at the center of what Section 28 is trying to do. The interesting thing is that the immediate impact of introducing the clause was to bring lesbians and gay men together to an unprecedented degree and to cause a tremendous mobilization of common purpose, more successful than anything else could possibly have done. That’s very instructive. All the evidence of the history of the lesbian and gay identities is that the identity emerges most strongly when it is being threatened and challenged. In a sense the identity emerges as a reflex against the social efforts to inhibit relations between homosexual people. So the Government has first of all managed to mobilize gay and lesbian people to an unprecedented degree. It’s been counterproductive.

The second thing it has managed to do is to offend liberal opinion much more generally. In the immediate aftermath of the introduction of Section 28 in December, there was a total embarrassed silence from the left intelligentsia. They didn’t quite know how to react. That suggested to me at the time that the Thatcherite moral agenda had bitten very deeply. But within a couple of months the mobilization of liberal opinion around the censorship issue produced a tremendous wave of support for lesbians and gays. That suggests to me the way in which our hand can be strengthened when we’re able to generalize our cause into a much wider cause. On this issue it was censorship. But there are other issues that can equally effect a wider mobilization—AIDS is an obvious one—where you can leap beyond your particular concerns to more widely appreciated concerns, which other people who are not gay can identify with. So the Government has achieved two things, which are completely counter to its intentions.

A third point I want to make is that there is now evidence that the section is inoperable anyway. Legal opinion being given to the Government apparently suggests that Section 28 is in contradiction with other legislation that the Government introduced the previous year. Section 28 was designed to prevent the promotion of homosexuality in schools by local authorities, who control most local education. The previous year, however, they’d introduced an act on sex education which took powers away from local authorities to give sex education and put that power into governors of schools or trustees. So local authorities legally don’t have the power to promote homosexuality in schools through sex education even before Section 28. Section 28 makes no reference to schools not being able to give sex education to promote homosexuality. So the main focus for sex education is outside the remit of Section 28.

MS: So this will then depend on the good will of school governors?

JW: If school governors wanted to allow school teachers to promote homosexuality, there’s nothing in Section 28 that inhibits them. That’s the paradox. They’ve taken powers away from local authorities, which it turns out by a reading of their own legislation they didn’t have anyway. So from that point of view, Section 28 was a dead letter from the start, which no one realized, including the Government’s own legal advisors. That doesn’t mean that Section 28 isn’t important. It could still color the whole climate of attitudes toward homosexuality and still be very dangerous.

MS: I imagine the governors would be hard-pressed to do this even if the local councils were not involved.

JW: That’s right. But local councils were never intending to promote homosexuality anyway. What does promote homosexuality mean? The most that has been attempted by certain leftwing Labour councils has been to encourage schools to develop policies which allow positive images of homosexuality to be presented to children, which isn’t the same thing as promotion of homosexuality. Promotion suggests that schools are being encouraged to tell kids that you must be homosexual because this is the only way to live, but no one’s ever suggested that.

MS: So then it seems that Section 28 also cuts into the historical divisions between gay rights privacy advocates and liberation advocates? Because if the whole issue is public promotion, that seems to be more an item on the liberation agenda. I can imagine privacy advocates, or liberals in general, saying that Section 28 is O.K., that we’re just asking for the right to do what we want to do behind bedroom doors.

JW: Well the argument in those terms has never been central in Britain anyway. The privacy argument has been the classical liberal argument that predated the emergence of an active gay politics. Sex legislation is Britain since the ‘60s has been shaped by what I call the Wolfenden strategy, named after Sir John Wolfenden, who produced a classic report on homosexuality in 1957. Basically what that does is make a classic distinction between what is allowed in public, which should come within the scope of the law to prevent “indecency” in public, and what is allowed in private, which is a matter of individual choice. So homosexuality was decriminalized in 1967 precisely on the grounds that if it happened in the streets or in public places it should be illegal because it offended public decency. But if it happened in private, whatever public opinion thought about it, it should be allowed to happen, as long as you’ve very narrowly defined what is private. That formulation has been the one that’s governed all legislation on sexuality, not just homosexuality, since the late ‘60s. Now gay liberation of course fundamentally challenged that and argued essentially that homosexuals had as much right to display their affection in public as heterosexuals and that homosexuality should be publicly affirmed as a valid lifestyle.

What’s going on with Section 28 is very much a feeling on the part of the Government that the compromise of the ‘60s, the division between public and private, has been breaking down, that homosexuals have gone too far, beyond this compromise. They’ve breached the boundaries of what is private and not private. Section 28, read in this way, can be seen as an attempt to say, “We want you to go back to 1967.” It’s not yet saying, “We want to go back before ’67. We don’t want to make homosexuality illegal again. We want to fall back to the position that was agreed in the historic compromise of 1967.” That’s what the Government is saying. And I think to some extent that is what it is doing. Because I don’t think there’s any strong head of steam to make homosexuality illegal as such, but there certainly is an attempt to privatize it again.

MS: It seems to me, then, that that calls for the movement to respond in a very publicly confrontational way.

JW: Which it has done. There have been several national demonstrations against Section 28 (two held in London, one in Manchester), which were larger mobilizations of lesbians and gays than ever before in British history. The last one, at the end of April, had 30,000 people. That’s small by American standards, but it’s huge by British standards. The largest previous march was about 15,000 at the gay pride march the year before. This brought out many people who in no sense regarded themselves as political at any period before. It’s had a tremendous impact in that sense. Also particularly interesting is that some of the militant people organizing the march, campaigning against Section 28, have been lesbians. A large number of young lesbians have been incredibly active, working with gay men, which I think is a very exciting development, completely unprecedented over the last fifteen years.

MS: That’s certainly the case with the more political AIDS activist groups in the United States, too.

JW: I’m not sure that it’s as true in AIDS work in Britain, although there are large numbers of women, including lesbians, involved. It’s over Section 28 that the political mobilization has taken place, rather than AIDS, because AIDS is still relatively small in Britain compared to the United States.

MS: Going back to the 1967 compromise you described before, the situation of course is different in the United States, where there are still anti-sodomy laws in state statutes.

JW: Well I should say that anti-sodomy laws are still on the statute books in Britain for heterosexuals. Buggery is illegal between heterosexuals in theory, although in practice it’s never operated. Homosexuality was not made legal in 1967. Certain forms of homosexual acts between consenting adults in private aged over 21 were decriminalized. And that’s an important distinction. Because judges have since made clear that homosexuality is not technically legal in Britain. But nevertheless what you say is true. This modest reform in 1967 has decriminalized homosexuality in a way that isn’t true in the United States. There’s an interesting paradox, because it was in the United States in the 1970s that there was a huge explosion of public forms of gay activity, like the bathhouses. Because the British law of 1967 so sharply and clearly defined what was allowable and what was not, there was never any possibility in Britain of the development of a similar sort of public sexual activity. Privacy was very narrowly defined as being two people, behind locked doors. So we didn’t see in the ‘70s in Britain the same sort of explosion of sexual social facilities for gay men, although we did see the emergence of clubs and discos, similar to the United States.

MS: What aspect of the GLF’s work were you involved in?

JW: Well I wasn’t very good at organizing discos or demonstrations. The work I was involved in at the beginning was the sort that involved my particular skills. So I got involved very early on in collective writings. I was involved in the Counter-Psychiatry Group, which attempted to challenge orthodox psychology. And I was involved in producing one of the first pamphlets that came out of the British gay movement, called “Psychiatry and the Homosexual,” published in 1972. In addition to that I organized a gay society at the London School of Economics, which became a focus for discussion about cultural aspects of gay politics. And then I got involved in gay socialist groups, from about 1972 onwards. From 1974 I was involved in producing Gay Left with a collective of six or seven other men, which was an attempt to develop a synthesis of gay and left politics, the last of which came out in 1979, and produced a book, which came out in 1980. That was really most of my activities for the ‘70s. During the ‘80s, I’ve been much less involved in day-to-day activity and much more involved in writing. And I’ve produced three books and also gay journalism and increasingly in broader political writing, so less actively involved in movement things, although giving occasional talks. Not so much grassroots activism.

MS: You’ve been credited with fully developing the emergence hypothesis, which was originally formulated by Mary McIntosh and argues that while homosexual behaviors have always existed, the homosexual and the homosexual identity are particular historical phenomena that emerged during a specific historical period. What intellectual stage is that idea at now? What does it play in the movement and gay activism?

JW: I think it’s been the most important theoretical breakthrough in writing not just about homosexuality but about sexuality in general over the last twenty years. What it’s put on the agenda is the fact that sexual identities are culturally specific. If we take that seriously, then we can begin to explore the social forces that actually shape sexuality at any particular period.

In relation to the emergence of the homosexual identity in the nineteenth century, what all of the work shows to me is that we can only understand gay history if we see it as the culmination of two processes: a process of social definition and a process of self-definition. The social definition comes from a variety of sources—legal, medical, psychological, sexological, and so on—all of which, in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, have attempted to rigidly demarcate what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior by classifying types of people. People are classified as sick, for example, deserving of medical attention, or psychologically unbalanced or perverted.

Sexology has been absolutely central in this process. If you look at the history of sexology, you actually see this whole debate very clearly, an attempt to put on a scientific basis the idea that there is a particular type of person different from other types of people. These social definitions didn’t create the homosexual identity as such; what they did was attempt to make sense of, demarcate the limits of, struggles for self-identification, which were going on on the ground. In a sense, the whole sexological, psychiatric, and medical/legal attempts to define the homosexual person were a response to the fact that homosexual people were themselves attempting to define themselves during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. So you find a dialogue going on between, on the one hand, these hostile labelings of people as sick and perverted, and, on the other, an attempt by people thus defined to make sense of themselves in terms of these inherited labels, but, as far as possible, reversing them, so that a term like homosexual has a dual meaning. It’s a hostile labelling, but at the same time it’s an attempt at an affirmative identity, used by gay and lesbian people themselves.

We can see this clearly if we look at certain key moments. In the late nineteenth century, we see the rapid emergence of terms for homosexual people, terms like the third sex, the intermediate sex, the uranian, or the urning, which were attempts, often by homosexual people themselves, to say that there is something there that is a distinctive identity. A second moment was in the ‘60s and ‘70s, with the rapid emergence of terms like gay to describe ourselves. What you see there is not the invention from nothing or the imposition of an identity, on people, of homosexuality, but actually an attempt to make sense of a sense of difference from other people. So during the course of the twentieth century, you do actually see very clearly the emergence of a separate categorization of people, on the grounds of their sexuality. And that is part of a much broader process, not confined to lesbian and gay people. It’s a much wider process of the growing centrality of sexual identity in people’s sense of self over the last two to three hundred years.

The argument has never said that people were not homosexual in the broader sense before the nineteenth or eighteenth century. It doesn’t say that people didn’t have a sense of being different. What it does say is that the idea that you can base your identity, your place in the world, on your sexuality, and specifically on your gay sexuality, is something very new to western civilization. The gay identities that have emerged over the last hundred years are distinct from the homosexually-defined identities that may or may not have existed at different periods in the past.

What I call the social constructionist argument says that sexual identities are very culturally specific. And if you try to trace the evolution of an identity which we inhabit today from the year zero, ten thousand or ten million years ago, then you are learning almost nothing, because you don’t actually discover what is specific about the identities we now live. My belief is that the identities we now live have been shaped by historical forces and self activity in a distinct historical period. If we understand the forces that shaped our identity, including our own involvement in shaping them, then we begin to understand something about the culture in which homosexuality has been disapproved of.

MS: It seems that there’s a paradox in that as a gay identity has been constructed, there a process by which people become so much less aware of that construction. This leads people to believe that there has always been a gay identity and that seems to present problems in the gay movement, that lack of consciousness about that process.

JW: Social movements notoriously have a poor sense of their own history, because what’s important to social movements is their sense of today. Because gay people feel so strongly that we are what we are now, then we must always have been like this. But if we just look back on our own lives, we are aware that we have not always been as we are now. Our own consciousness has changed dramatically over the last twenty years and is changing now in the wake of AIDS and government repression. It constantly changes. It’s quite conceivable that it will change quite dramatically in the future. We need a better sense of our history, not simply for its own sake, but so we are aware of the forces that we are combatting and the constant need to keep ahead of those forces.

The analytical position that says that the homosexual identity is a historical identity doesn’t in any way deny the importance of gay and lesbian struggles. On the contrary, because it understands why these identities have emerged, it actually underlines the importance of those identities. They’ve emerged because they have a historic function. They haven’t emerged out of the heads of academics. They’ve emerged out of the struggles of gay and lesbian people themselves against the forces which have been attempting to deny the validity of their sexual feelings. And I think it’s very important that we recognize this. I know many activists over the years have said that the social constructionist argument denies us our history. On the contrary, it gives us our history. It shows why we are where we are today. We don’t need to strengthen our hands by saying that we are the descendants of people who existed ten thousand years ago. We are placed today in real struggles.

I would go broader than that, though. What I’m saying about the lesbian and gay identity can be paralleled on all sorts of other identities as well. The one I always parallel it with is the idea of the working class identity. Again, it’s very tempting when looking at working class history to suggest that there have always been workers, always been employers, always been a wage-capital relationship. But in fact we know from very excellent work by Edward Thompson that the working class has formed itself in a relatively recent history.

MS: So that would be true of identities based on race and sex?

JW: Yes. People have always been demarcated by skin color in western cultures and yet the idea of a distinctive black identity, with a history of its own, is actually a very recent historic phenomenon. In Britain, we see the parameters of a black identity shifting all the time. In left discourse in Britain at the moment, black means people of Afro-Caribbean and Asian descent. It’s a general label for people involved in struggle. It’s a political label rather than simply a description of skin color. In the same way the lesbian and gay identity is a political identity. I know we feel it deeply personally. But it’s essentially an oppositional identity that’s emerged in historical circumstances to defend the rights of homosexual peoples to define their own sexualities.

MS: Many believe that the social constructionist argument is more relevant for sexual and class identity, but more problematic for race and sex, because people seem to take these as much more natural categories.

JW: Well I think all social identities are based on distinctions that are more than simply social, either differences in sexual feelings or gendered feelings or skin color. The important thing isn’t what the biological origins of an identity are, but the social meanings given to those biological or other differences. That’s what’s historically important.

MS: Would you say that social constructionism is more accepted among gay scholars working in gay studies than people working on race and sex?

JW: Well I think many gay academics, especially those influenced by sociobiology, wouldn’t necessary agree with the social constructionist view either. But by and large the social constructionist view has hegemonized gay and lesbian studies in a way which it hasn’t in feminist studies or black studies, although there is a very important strand within feminism which does recognize the importance of social constructionism.

I think the problem is that of cultural nationalism, an attempt to define yourself against others by tracing your roots back into the mists of time. It’s probably emotionally necessary at certain moments in the evolution of any identity, especially identities related to political struggle. But there’s a limit to that. In the end all you get is separate histories, unconnected with one another. What is particularly interesting to me is the way in which these distinctive identities emerge and are felt as distinctive and are in fact all part of a common process. So for instance you can’t understand lesbian and gay identity unless you understand the changing balances between the genders over the last two to three hundred years. It’s quite clear that one of the roots of hostility to homosexuality was that it disrupted the expectations of what it was to be an appropriate man or woman in an evolution of distinctive gender identities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. So there’s a need to make connection between gender differences and sexual differences. In the same way you can see a close interconnection between racial categorization and sexual categorization over the last ten to twenty years, with the emergence of distinctive black lesbian and gay voices arguing that the lesbian and gay identities which have emerged are culturally specific white identities. And you see the reformation of lesbian and gay identities along racially specific lines.

The point is that social identities are gendered, racialized, and sexualized. As individuals, we hold various identities together. There’s no such thing as a simple heterosexual who’s different from a black person who’s different from a woman. Simultaneously we can be black or white, gay or straight, male or female. Identities are complex. We negotiate the hazards of identity through a whole range of possible subject positions. These negotiations are taking place increasingly in a world where identities are not given because of the rapidity of social change. It’s no longer possible to say that I come from Middletown and I’m a white person and I’m a man and I’m straight and all these things mean the same thing. They don’t. You can be black, gay, geographically mobile, a Mormon. And you hold them together, often in contradictory positions. It’s that contradictory nexus that makes our social identities so complex, which at the same time makes it so politically important that we see the centrality of identity and social location in the world today.

MS: Would you say that AIDS is a watershed in the evolution of gay identity? Does AIDS complete one project that you are describing, since there can be little doubt now in the public eye that there are homosexual people with homosexual identities?

JW: The gay community has been able to survive AIDS because of what happened in the previous fifteen years: the emergence of strong lesbian and gay identity. There’s a sense in which gay people may survive AIDS better than nongay people because we already have the social support network that other communities lack. There’s a paradox in that. Those social support networks, particularly the sexual networks that so many gay men have, have been the reason that AIDS has spread so rapidly in our community. The history of the last fifteen years is both the locale for the spread of AIDS but also the strong concrete base on which our survival has been predicated. That’s the real historical and tragic irony. Although in western countries gay people have suffered most so far from AIDS, I think we are likely to survive it better than other communities and groups that are affected by AIDS. What it’s done is actually strengthen lesbian and gay identity because it’s seen as and experienced as a tragedy that affects the whole community and not just individuals within that community. A post-AIDS identity will exist because of the strength of the gay identity as it developed over the previous fifteen years. In a strange sort of way, AIDS has ensured the survival of the gay identity.

I think people realize that this is something that’s on their agenda as well as other people’s agenda. It’s not seen as something that happens to other people and I can escape it. People realize that they might get it themselves, or even if they don’t, because they’ve grown up in a culture of safer sex activity, it might affect people they know and love and therefore it involves them more deeply.

This is one of the paradoxes of the situation. Despite AIDS, and despite what in Britain is increased hostility toward gay people on an individual level, at the same time there is public knowledge of homosexuality and acceptance of certain representations of homosexuality.

Marc Stein is the Jamie and Phyllis Pasker Professor of History at San Francisco State University. He is the author of Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (2012), Sexual Injustice: Supreme Court Decisions from Griswold to Roe (2010), and City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972 (2000).

Jeffrey Weeks is a Research Professor in the Weeks Centre for Social and Policy Studies at London South Bank University. Following teaching and research posts at the London School of Economics, Universities of Essex, Kent, Southampton and the West of England, he was appointed as Professor of Sociology at LSBU in 1994. Having written extensively about gay and lesbian history over the last four decades, his most recent books are The Languages of Sexuality (2011) and a fully revised 3rd edition of Sex, Politics and Society (2012). He is currently working on a book entitled What Is Sexual History? to be published by Polity Press in 2015/16.

Jeffrey Weeks is a Research Professor in the Weeks Centre for Social and Policy Studies at London South Bank University. Following teaching and research posts at the London School of Economics, Universities of Essex, Kent, Southampton and the West of England, he was appointed as Professor of Sociology at LSBU in 1994. Having written extensively about gay and lesbian history over the last four decades, his most recent books are The Languages of Sexuality (2011) and a fully revised 3rd edition of Sex, Politics and Society (2012). He is currently working on a book entitled What Is Sexual History? to be published by Polity Press in 2015/16.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com