“Having sex on your period is absolutely safe,” reassures OB-GYN and talk-show regular Dr. Laura Berman. Like most sex experts in the past half-century, Berman is ready to demolish old menstrual taboos and usher in a modern period. And like many educators, physicians, and cultural critics who have written about menstruation, she frames her recommendations within a historical narrative: in the old days, religious proscriptions and folk traditions labeled menstruating women as “dirty” or “unclean” and therefore unfit for intercourse; now, in the light of modern science, we know better.

When it comes to menstruation, this sweeping narrative arc can feel persuasive, since ancient attitudes have in fact been strikingly persistent. And yet, the leap from the biblical book of Leviticus to the twenty-first century obscures as much history as it reveals. It turns out, when we listen to a range of voices, from natural philosophers to medical writers, to ordinary women and men discussing their experiences, the history of menstruation and sex is more complex. All of these parties gingerly navigated the shift to the modern period, with results that are perhaps less fully liberatory than advocates like Berman might acknowledge.

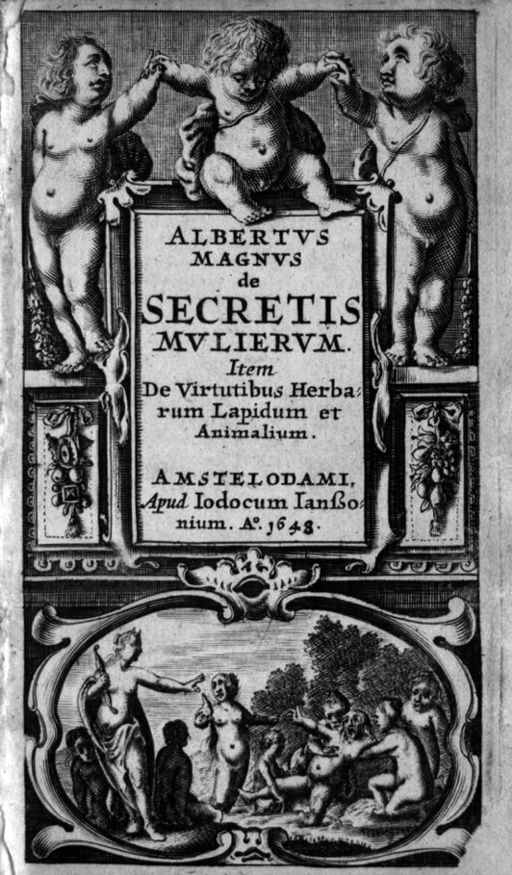

Ancient prejudice against sex during menstruation persisted for many centuries. Medieval authors elaborated upon biblical and classical opposition to intercourse during a woman’s menstrual period and argued that menstrual blood might either contribute bad material to the conceptus or endanger it, but either way, it could produce monstrous or damaged offspring. By the nineteenth century, German scientist Theodor Ludwig Wilhelm von Bischoff demonstrated that dogs ovulate spontaneously, and he and other scientists speculated that women did too. Scientists suspected that ovulation was related to the menstrual cycle and equated menstruation with “heat,” or estrus, in animals. Popular medical writers, who urged the white, middle-class audiences to have more children, seemed to implicitly advocate sex during menstruation.

Yet, longstanding cultural taboos continued to inflect ideas about sex during menstruation among medical writers. Charles Malchow declared in 1923, “It is not so much the want of desire on the part of the woman as it is the consciousness of being unfit, or the fear of contaminating or causing disgust, that prevents the proper mood for intercourse.” What a relief it must have been to Malchow when, a few years later, scientists Kyusaku Ogino and Hermann Knaus demonstrated that ovulation happened between menstrual periods and not during them. There was no need for men of science to advocate for sex during menstruation after all.

Women themselves, and their partners, wrestled with the question in their own lives, as they explained to me in interviews. These same interviews about menstruation also revealed a common experience of sexual coercion and intimate violence. For their part, older women I interviewed avoided intercourse during menstruation, but generally not out of fear of provoking male disgust. Mary Hanson*, a white New Englander born in the first decade of the twentieth century, came the closest to expressing her feelings in those terms. “[D]idn’t they tell us it was our bad blood? Why would a man want to have anything to do with it?” But Ida Smithson, an African-American born in the 1910s in the rural South, had a different way of explaining why sex during menstruation was inappropriate. She regarded menstruation as similar to lochial bleeding after childbirth. It was a delicate time for a woman, and her body needed healing and cleaning out. She thought that people who had sex during menstruation “don’t have no scruples,” but not in terms of sinfulness. She was bemoaning the bullying of men who said, “You are my wife, you’re my girlfriend, I tell you what to do.” Liza O’Malley, a white New Englander born in the 1930s, agreed. “I think the only time when I ever had it was when my husband was drinking and I couldn’t say no.” These statements, which reveal intimate partner violence, suggest that some men did not see menstruation as excusing women from meeting their sexual needs. Read slightly differently, women sought and sometimes failed to exert influence over their partners through adhering to this longstanding cultural taboo.

Many women a generation younger than Liza O’Malley who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s embraced the idea that it was safe for girls to do whatever they wanted during their periods. Menstruation was increasingly losing its status as a “gym excuse,” and physicians approved even the traditionally-suspect activity of swimming. And yet, sex during menstruation was still unappealing. As Roberta Cummings Brown explained, it was a lot of trouble afterwards. “We just take this linen off and put some more on… Rinse it all in the bathtub to make sure that I hadn’t ruined my linen and nightgown or whatever.” The cleanup job fell on women, who had trouble enjoying sex when they were worrying about the mess.

The next generation of women and men, who went to college in the 1970s and 1980s, described to me a new way of thinking about sex during menstruation. As Peter Jefferson recounted, “I was dating a woman who was the last reincarnation of Earth Mother… it was like, ‘I’m having my period, but it’s OK’… And so we went ahead and made love and it was like, ‘wow! It was OK. OK! All those things those guys had told me about, you know, ‘It’s gonna fall off.’” Some young women described taking offence if their boyfriends shied away from having sex during menstrual periods. This generation grew up in the aftermath of the sexual and feminist upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s.

Several generations of American women and men moved gradually and unevenly toward a view of sexuality in which menstruation would no longer serve as a constraint. Stripping periods of stigma rendered sex during menstruation like any other activity—gym class, swimming, school, and work—something that could be done by a modern woman with the right attitude all month long. The modern period promised pleasure but it also demanded that women be sexually available without fail. The modernization of menstrual sex, like sexual modernity itself, resulted in an emphasis on sexual availability and variety without fundamentally altering the gender hierarchies that made these relations both sites of pleasure and danger.

* All interviewees have been given pseudonyms to protect their privacy.

Lara Freidenfelds is the author of The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America, which was awarded the Emily Toth Prize for Best Book in Women’s Studies from the Popular Culture/American Culture Association. She blogs with the historian’s perspective on sex, reproduction, and women’s health in America at larafreidenfelds.com and tweets from @larafreidenfeld.

Lara Freidenfelds is the author of The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America, which was awarded the Emily Toth Prize for Best Book in Women’s Studies from the Popular Culture/American Culture Association. She blogs with the historian’s perspective on sex, reproduction, and women’s health in America at larafreidenfelds.com and tweets from @larafreidenfeld.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I think the history is more chequers in earlier times, too. Interesting that in the Hippocratic gynecological texts there is no advice against sex while menstruating. On the contrary it is seen as a good time for conception because the womb must be ‘open’ so the male seed can get in! They advise against sex during the heaviest flow on practical grounds – the seed will get washed out again – but while the flow is waning is an ideal time. Of course, it helps that at this time menstrual blood was seen simply as excess normal blood. I wrote a short piece on this on https://theconversation.com/four-weird-ideas-people-used-to-have-about-womens-periods-30623 which may be useful.

Thanks for your comment, Helen. Do you think the more matter-of-fact attitude in the medical sources was reflected in popular attitudes and practices? I know the sources are scarce, but are there any textual hints that might point one way or the other?

Really hard to tell, Lara – I don’t know of any jokes, for example, suggesting popular unease, and there’s no sign of any menstrual seclusion practices. There are taboos in religious cults about excluding from the sanctuary those who have had contact with menstruation, sex or death, but they tend to be from slightly later than the Hippocratic gynaecological treatises anyway. Fascinating to speculate!

Sorry, should be ‘chequered’ not ‘chequers’ – autocorrect moment!!