The fiftieth anniversary of the 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut Supreme Court decision, which struck down state laws that banned married people’s use of contraceptives, arrives in the midst of fraught contests across the United States over women’s access to reproductive healthcare. From last year’s Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Supreme Court decision, which allowed employers to opt out of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) reproductive healthcare mandate for health insurance plans if it violated the employer’s religious beliefs, to more recent Congressional proposals to prohibit abortion after 20 weeks, religious voices echo throughout American debates over reproductive choices and healthcare options. Religious institutions and individuals typically appear in histories of reproductive rights as foes of women’s reproductive choices. The Catholic Church was at the forefront of organized opposition to legal contraceptives in the twentieth century, and Catholics united with conservative Protestants to challenge legal abortion in the wake of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.

The loudest voices in these debates tend to be the conservative ones. But as three scholars showed at a panel on “Religious and Reproductive Politics” at the April 2015 meeting of the Organization of American Historians (the professional organization for scholars of North American history) in St. Louis, religious activism in defense of women’s reproductive rights has a crucial yet often overlooked history that demands our attention. More provocatively, these histories of religions and reproductive rights challenge the idea that either religious beliefs, leaders, or institutions are more likely to oppose women’s reproductive freedoms than support them. Instead, they show that many previously overlooked individuals, acting upon religious beliefs and asserting their religious authority, have been forceful, effective advocates for reproductive rights.

Starting in the 1960s, as Samira Mehta showed, liberal American Protestant ministers praised the benefits of the oral contraceptive pill. They did so by crafting a theology of “responsible parenthood” that was both intimate (improving relations between a wife and husband) and global (safeguarding the future of the planet through zero population growth). The reasons for liberal Protestant support for the contraceptive pill had little if anything to do with the sexual revolution or feminism. To the contrary, ministers praised the pill as a means of enabling women to bear only as many children as their husbands’ salaries could support, so families could maintain a middle-class standard of living and mothers could stay home to care for their children. This support for oral contraception was unambiguously religious, as Mehta showed:

Voices at every level of Protestant Mainline life endorsed the use of contraception, framing it as a Christian duty. It was a Christian responsibility to be good stewards of the earth by not taxing it with excess population, and Christian parents owed their children the attention and economic support made possible in planned families.

The point, Mehta makes clear, is not that mainline Protestants were sex radicals. Rather, they found ways to support women’s safe, legal access to contraceptives within a moral framework that upheld traditional ideas about family life and ethical stewardship of the earth’s resources.

Rachel Kranson brought to light the efforts the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism (WLCJ), a national group with thousands of members, which passed a unanimous resolution at its biennial conference in 1970 supporting “freedom of choice” with respect to a woman’s right to abortion. (The Conservative movement in Judaism follows Jewish law but tends to be socially progressive.) These women did not have any support from Conservative rabbis, an unusual exception for a group that typically consulted with the male rabbinic leadership on issues related to Jewish law. Rather, these women put abortion on the agenda for the Conservative movement. The WLCJ achieved mixed results. Kranson argues that had the group not issued its challenge to the Conservative movement in 1970, the rabbis might have avoided the issue entirely. By 1982, Kranson shows, the WLCJ had ceased to describe abortion as a woman’s right, instead describing it as matter of first amendment protections for religious practice. This shift represented a political compromise to reconcile the feminist goal of ensuring women’s reproductive freedoms with Jewish law, which understood abortion as a matter of emergency health care, not woman’s bodily self-determination. Within a year, the Conservative movement had become the first Jewish denomination to declare its support for women’s access to legal abortion. Kranson’s work thus highlights the paradox of Conservative Jewish support for abortion: it fulfilled a feminist goal of the WLCJ, yet did so by reframing the right to an abortion within the patriarchal institutional culture of the Conservative movement and by dropping claims to women’s sexual autonomy.

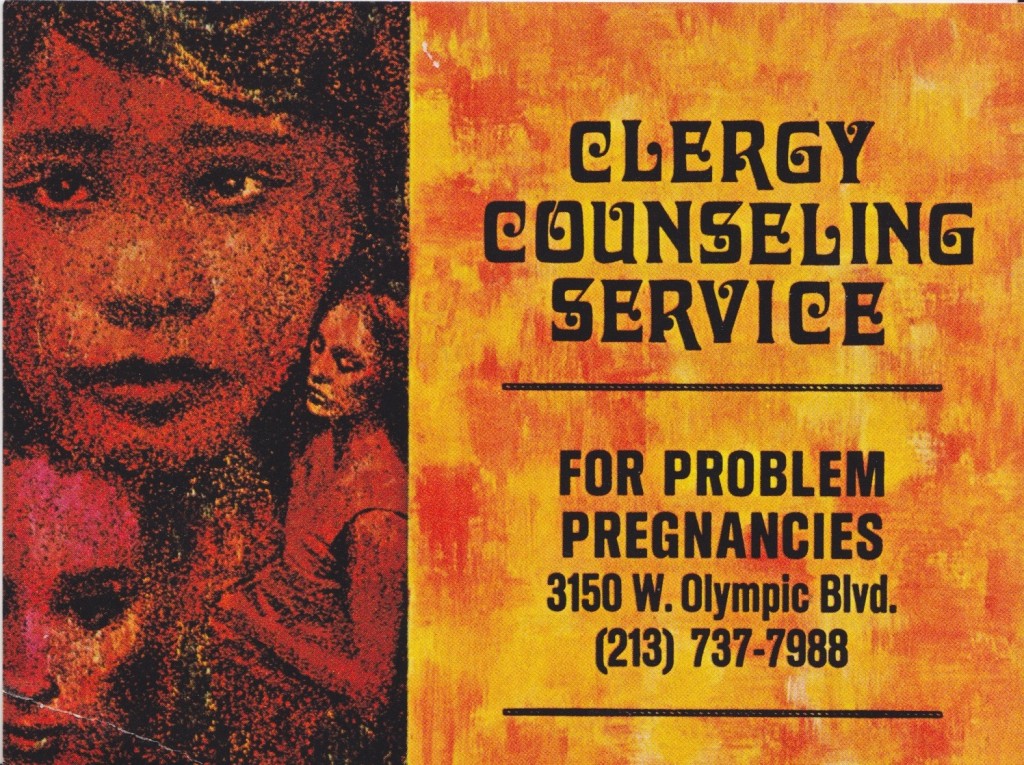

Perhaps the most surprising story to emerge from this panel was the remarkable history of the Clergy Consultation Service (CCS), the topic of Gillian Frank’s presentation. Starting in 1965, when it was illegal to provide or obtain an abortion in the United States, religious leaders created from scratch a massive abortion referral network. More than two thousand liberal Protestant ministers, Reform rabbis, and even some Catholic priests, together with their congregations and wealthy supporters, worked in forty states and more than fifty U.S. cities, with affiliates as far-flung as Tokyo and Montreal. They became conduits for information about how to access safe abortions and the funds to pay for them. As Frank explained:

In five years, the group helped somewhere between 250,000 to half a million women obtain legal and illegal abortions from providers in Canada, England, Japan, Mexico, Puerto Rico and the United States…. CCS, in other words, was one of the most significant means by which women accessed abortion in the years when it was illegal.

The CCS maintained lists of credible abortion providers, provided women with travel information when necessary, and raised funds to pay for women’s transportation to and from their abortionists. By collecting reports from the women about their experiences, the CCS also kept track of the quality of care that pregnant women received, blacklisting unethical or unsanitary providers. They also tracked the price of an abortion and helped women find quality healthcare at affordable prices, work that ultimately pushed down the cost of an abortion, from an average of $900 in 1965 to $125 by 1971. Frank is gathering oral histories from dozens of clergy who participated in the CCS, and his forthcoming book will undoubtedly reveal a sweeping, previously unknown history of how religious leaders built their activism around their faith and moral principles when they helped women break American laws against abortion.

What stands out from all three papers was the intensity of the spiritual commitments of the religious people who advocated for women’s reproductive health care and rights between the 1960s and 1980s. The clergy who participated in the CCS acted from a sense of moral and religious calling: “There are higher laws and moral obligations transcending legal codes,” they wrote, and stated that it was their “pastoral responsibility and religious duty to give aid and assistance to all women with problem pregnancies.” The Jewish women in the WLCJ were determined to build bridges between their feminist politics and their religious beliefs, forging a Jewish legal framework that understood women’s reproductive rights as a matter of religious concern. Liberal Protestant clergy celebrated the potential of the contraceptive pill to strengthen family bonds and safeguard the earth, thus forging a theology of reproductive rights that intersected with their social and spiritual commitments to family life and environmental responsibility.

These three papers, rich with insight and possibility, suggest that we are only beginning to understand the role of “religion” in American debates over reproductive rights. They show how progressive as well as conservative voices have shaped American women’s access to contraception and abortion. These preliminary findings already point to surprises and paradoxes—of conservative arguments marshaled for progressive causes, of the key roles played by male clergy to produce official statements in support of women’s reproductive healthcare, and of the hidden history of illicit religious philanthropy to enable women to evade restrictive abortion laws. The loudest religious voices in our debates over reproductive health care tend to be the most conservative, and in recent years, they have had an outsized influence on national and state reproductive health care policies in the United States. What these three scholars suggest is that we would be wise not to assume that “religion” necessarily leads to any particular set of beliefs about the morality of contraception or abortion. Religious actors have shaped the history of women’s reproductive rights in surprising ways.

Rebecca L. Davis is an Associate Professor of History and Women and Gender Studies at the University of Delaware. A scholar of marriage, sexuality, and religion in American culture, Davis is the author of More Perfect Unions: The American Search for Marital Bliss. Her article, “’My Homosexuality Is Getting Worse Every Day‘: Norman Vincent Peale, Psychiatry, and the Liberal Protestant Response to Same-Sex Desires in Mid-Twentieth-Century America,” received the 2011-2012 LGBT Religious History Award from the LGBT Religious Archives Network.

Rebecca L. Davis is an Associate Professor of History and Women and Gender Studies at the University of Delaware. A scholar of marriage, sexuality, and religion in American culture, Davis is the author of More Perfect Unions: The American Search for Marital Bliss. Her article, “’My Homosexuality Is Getting Worse Every Day‘: Norman Vincent Peale, Psychiatry, and the Liberal Protestant Response to Same-Sex Desires in Mid-Twentieth-Century America,” received the 2011-2012 LGBT Religious History Award from the LGBT Religious Archives Network.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com