In the early 1930s, after attending a showing of This Nude World at the Castle Theater in Chicago, Alois Knapp and his wife Lorena decided to convert their 200-acre farm located in Roselawn, Indiana into a nudist camp. Although they had never dreamed that they would go into the “nakedness business,” the idyllic scenes that they had seen on screen—of nude men and women frolicking naked in Germany, France, and the United States—profoundly affected the couple, who had privately enjoyed “sunbaths for over ten years.” The couple thought that Lorena’s family farm, located fifty-five miles south of Chicago and surrounded by thick woods, could provide privacy and create the perfect weekend escape for men, women, and children to enjoy nature, sunbathing, and fresh air in the nude. The middle-aged couple gave “Zoro Nature Park,” founded on July 16th, 1933, a distinctly mom and pop character. In little more than a month, the small group grew to over fifty members. By October, Alois and Lorena limited the membership to two hundred in order to preserve the “community spirit among them.”

Until recently, migration into the cities in the twentieth century influenced historians of sexuality to focus primarily on the urban landscape as a key component of sexual liberalism. The history of nudism’s emergence in the United States reveals that sparsely populated rural areas proved more hospitable to the fledgling movement than did major cities. Nudists discovered that urban spaces, and the repressive movements and authorities there, accentuated the eroticism of the naked body while rural locations allowed for multiple and contradictory conceptions of nakedness that could be molded and constructed around health, family, and recreation. The American countryside—framed as a site of innocence—provided an ideal setting for the healthy, nature-oriented, and heteronormative principles of nudism and gave the movement the respectability necessary to develop and prosper in the United States.

Meeting at gymnasiums and private countryside retreats, small groups of men and women removed their clothes and participated in exercises that included tossing medicine balls, vigorous calisthenics, and swimming. Nudists believed that the experience of going naked was essential to maintaining physical and mental health. For many, the removal of clothing served as an important hygienic purpose since it freed the excretory functions of the skin from sweating garments that clung to the body and restricted free flowing movement. In addition, several early advocates wanted to reform what they considered to be a psychologically unhealthy conception of the body as shameful and erotic. American nudists contended that being naked with the opposite sex satisfied the “natural” curiosity to see and know about the body, promoted a “wholesome” way of thinking, and ultimately strengthened the relations between men and women.

The perceived eroticism of the naked body, however, remained a constant threat to the therapeutic character of nudism. Many social critics and moral reformers asserted that nudism’s therapeutic ideals and principles masked the movement’s effort to profit from the commercial appeal of the naked body. In cities like New York, local police, community leaders, politicians, and judges conflated nudist gatherings with a rapidly expanding sexual urban underworld. There, they believed, prostitutes used their scantily clad bodies to entice customers, while seedy bookstores, theaters, and newsstands brandished nudity for profit, and naked men met in bathhouses to engage in homosexual acts. Critics construed nudist activities as yet another form of commercial sexuality that needed to be removed from the city. The countryside had fewer regulations and nudist camps thrived there.

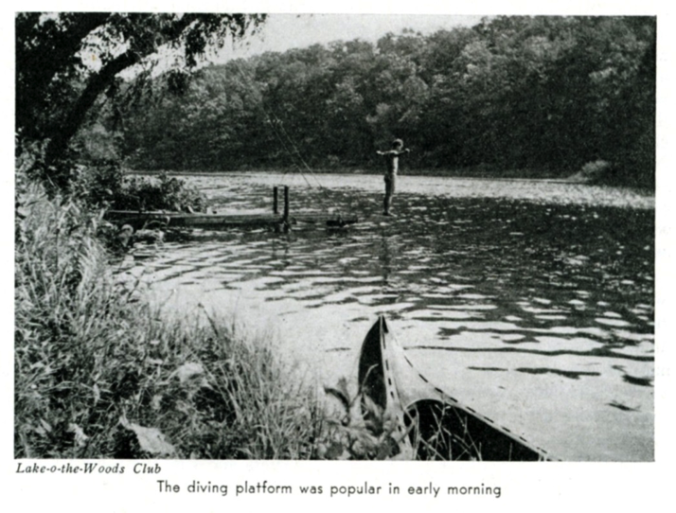

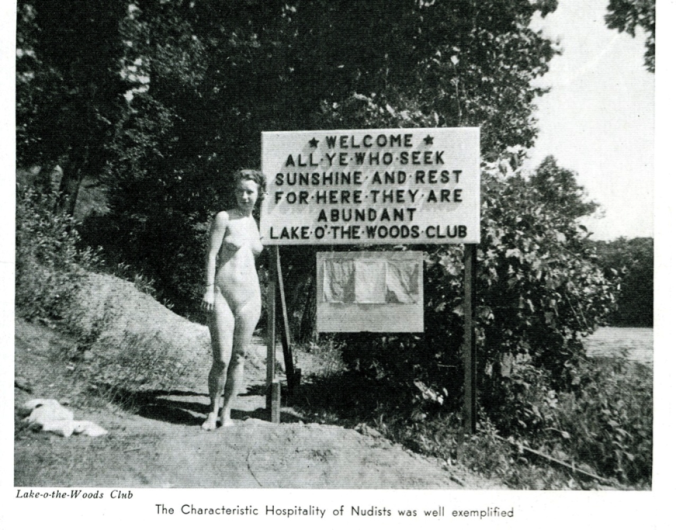

In the 1930s, a network of rural nudist camps that built on the idealized relationship between nature and nudity emerged in places like Indiana, New Jersey, and California and allowed urban residents to escape the noise, pollution, and stresses of the city and enjoy hiking, athletic competitions, swimming, rowing, and, of course, sunbathing.

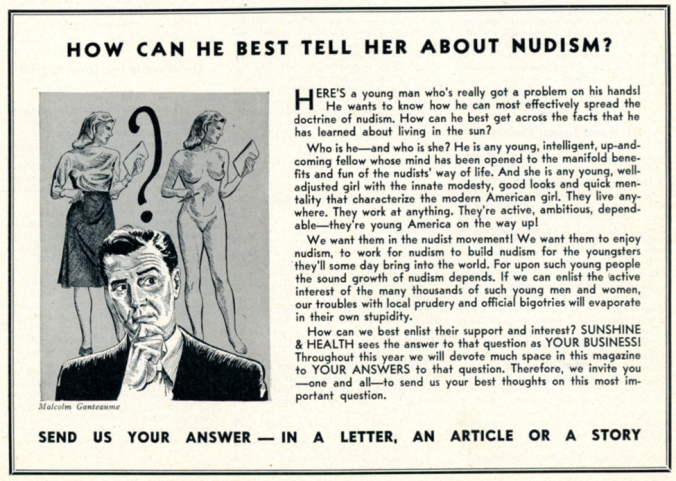

Although rural campsites offered urban dwellers a temporary reprieve from the close scrutiny they faced in cities, the nudist movement remained anxious to avoid criticism and legal trouble. Determining who posed a threat to the camps’ carefully managed atmosphere proved to be a continual source of struggle within the movement, revealing its heteronormative leanings. Without a wife or family to confirm their heterosexuality or moral integrity, single men elicited fears of homosexuality, posed a threat as potential voyeurs, and represented individuals who might pursue inter-generational sex. In the 1950s, the editors of Sunshine and Health (S&H), the nudist movement’s flagship magazine, explained that the “unlimited admission” of single men into a camp might “overbalance the membership of any group,” driving away families and defeating the very purpose of social nudism. The editorial reported that many nudists believed that the “motives of all single men who apply for nudist membership cannot be accurately known at the outset.”

During the Great Migration, white nudists feared the interaction of naked white and nonwhite bodies would negatively impact the image of the movement and “considered any discussion of this question as untimely.” One white man wrote to the editors of S&H, claiming that only a person with a “sinister object in mind” would want to bring other races into nudist camps. Urging members to “keep the nudist camps free from scandals,” he suggested that “separate camps for Negro and separate camps for white can [sic] hurt no one.” One camp in Jamal, California, explained its policy of exclusion with the statement: “Double prejudice is a long row to hoe.” Nudists felt that they had to “bend over backwards” to comply with the “rules and morals of a community.” While they might not have wanted to exclude people of color, many nudists believed that the “presence of Negroes would jeopardize the very existence of their camps because of pressure from prejudiced neighbors.”

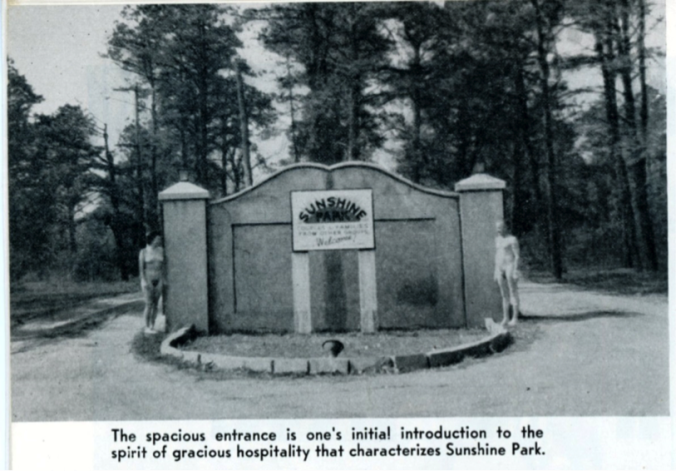

Amidst sexual and racial fears of the post-WWII period, the American nudist movement transformed its fledgling network of isolated rustic camps into well-equipped resorts ready to cater to young middle-class white families in search of leisure and recreation. Numerous articles in S&H advised prospective camp managers to identify grounds with large lakes, flowing streams, and bountiful vegetation if they wished to establish a successful club that would attract members and visitors. The movement was very much in step with the mainstream of consumer culture by creating a resort atmosphere that revolved around family, domesticity, and traditional gender ideals. In other words, nudists carefully created a space for its camps within the post-war vacationing experience.

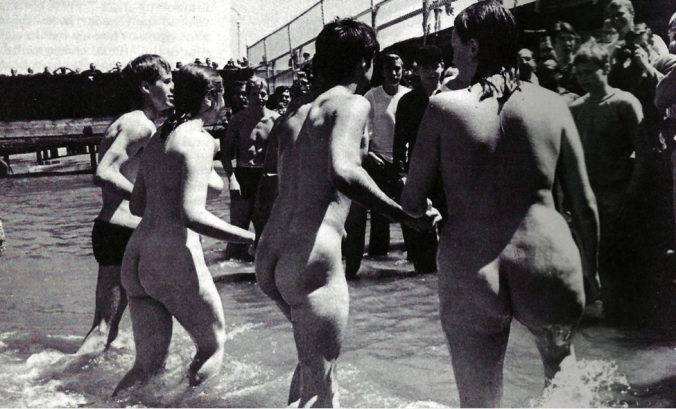

The respectable character of nudism at mid-century—with its emphasis on domesticity, racial homogeneity, and heterosexuality—clashed with the sexual revolution. The counterculture that emerged in the late 1960s saw public nudity as a way to challenge what they considered to be the hypocritical values and social customs of mainstream society. Yet, an aging nudist membership preferred their private, secluded, and rustic clubs and clung to rules restricting sexual behavior, while club owners maintained exclusionary policies based on race and gender. The rural spaces that had long provided refuge to so many nudist clubs came under attack from a generation seeking sexual liberation. Nudism at mid-century—revolting to many in the respectable middle classes—had its own politics of respectability that was hardly revolutionary.

Brian Hoffman received a PhD in history from the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. He is the author of Naked: A Cultural History of American Nudism (NYU Press, 2015). Brian has taught the history of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and American Studies at Wesleyan University. He currently teaches AP United States History in New Haven, CT. Brian tweets from @bshoffma.

Brian Hoffman received a PhD in history from the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. He is the author of Naked: A Cultural History of American Nudism (NYU Press, 2015). Brian has taught the history of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and American Studies at Wesleyan University. He currently teaches AP United States History in New Haven, CT. Brian tweets from @bshoffma.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Great post.

I take it there was little (any) participation in this rural nudism by the people who lived in the countryside? The picture I got from this was definitely one of middle-class urban vacationers, but it would be interesting to know if the rural middle classes took any interest, for instance. And were workers (whether urban or rural) threatening in similar ways to other racial groups?

@Pooley Thank you for your interest in my project and your excellent question. More than likely, it is safe to assume that the number of rural middle class or working class nudists would be quite small. Yet, it is almost impossible to say for certain since privacy and anonymity were so highly valued at nudist clubs/resorts. Nevertheless, there were many examples of nudists who lived in rural areas. The Sun Sports League in Allegan, Michigan was run by a music teacher from Kalamazoo in the 1930s and the camp had a few other members from nearby rural areas. Edith Church, one of early advocates of nudism in the United States, ran a nudist camp in rural Ohio for a number of years and lived nearby (although her home was fire bombed as a result). While they may not have been a majority of the visitors, I think it’s safe to say the rural middle class was represented by at least a few cottontails. As for workers, they were welcomed into camps as long as they were not single men. In the 1950s, a raid on a nudist club in Michigan led to the arrest of several factory workers, automobile plant operators, and supermarket cashiers. Dating back to its German origins, nudism offered to rejuvenate and reinvigorate the proletarian body.

It is very interesting that people in our society is actually into getting naked in public to seek relaxation. This blog shows that some people are very confident in the way they look under all the garments that hides their nakedness. I think people should understand that it should be your free will whether to be naked in public. Is that really a crime? I feel that it is also very interesting that there are resorts that promotes you to get naked. Being free is a right.

@Campbell Nudist resorts and clubs push the ideal of American freedom to its limit. While the United States celebrates itself as one of the freest nations in the modern world, it often imposes seemingly arbitrary restrictions on personal behavior and morality. Over the decades, nudists have challenged these boundaries over and over again in complex and contradictory ways- as evidence by the nudist camps discussed in this blog. More recently, in response to the policies of Facebook and Instagram, the #freethenipple campaign has taken up this effort.