On February 8, 1964, eleven clergymen, six physicians, and one economist gathered in an unheated conference room overlooking Rome. It had been almost a year since Pope John XXIII had set the group its task: preparing a response from the Catholic Church to the UN’s decision to instigate programmes of active population control. As discussions raged on, it seemed the Commission was moving further away from achieving its brief. When a Belgian Canon named Pierre de Locht suggested that marital sex could entail something more than just procreative purposes, papal theologian Fr. Bernhard Häring retorted, “But you are talking about questions of fundamental theology!” A pensive de Locht replied, “I suppose I am.” After a hushed pause, the Commission’s secretariat suggested they should break for coffee. The Commission members separated into groups to discuss the implications of what had been said; de Locht paced the balcony clutching his rosary.

Häring had understated, in fact, the significance of de Locht’s challenge, which called into question not only the content of Catholic moral theology, but also the processes through which the Church constructed this theology. The implications were clear: the Commission had the potential to challenge the very nature of Catholic epistemology. The opportunity for an unprecedented change in the Church’s doctrine was at stake.

Throughout its history, the Catholic Church had always considered the meaning and function of sex to be trans-historical, prescribed by the strictures of Natural Law. That the Church’s definition of sexuality could be shaped by human intervention represented an unprecedented shift in itself. The Commission therefore sat at the intersection of a number of significant post-war trends in the histories of sex and religion. Amidst widespread decline in church attendance across Western Europe, the monolithic maxims of Christian doctrine were being challenged like never before. Sexual fulfilment was increasingly seen by society to be central to not only a good marriage, but also a healthy sense of “self,” and sex was no longer considered to be a self-evident mechanism, but an intellectual topic to be studied and understood. The very existence of the Commission seemingly embodied many of the facets of a Sixties “cultural revolution.”

As the Catholic Church attempted to “modernise” its understanding of sex during the 1960s, certain ideas and assumptions underpinned those attempts and shaped the outcome. As this article shows, the Church recognised the historiocity of sexuality for the first time, but refused to engage with the personal, subjective dimensions of sexual experience. In not speaking to women about their own bodies, progressive Catholic authorities missed the historic opportunity to bring about meaningful theological change. It was this tension, beyond any other, that left the “modernising” processes of the 1960s stunted and unrealised. Ultimately, the story of the Commission is a tale of “what could have been.”

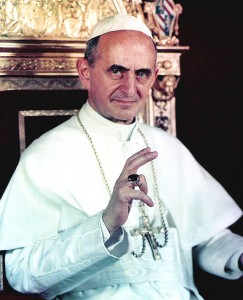

In response to de Locht’s entreaty in that marbled conference room, Pope Paul VI extended the Commission’s brief and membership. Initially, the Catholic hierarchy had expected the Commission to simply reiterate the Church’s existing stance on birth control: the primary purpose of sex was procreation and the use of any “artificial” means to prevent conception was deemed “intrinsically evil.” However, Pope Paul VI now gave the Commission full licence to scrutinise the Church’s doctrine on contraception and, if necessary, reformulate the Catholic understanding of human sexuality. To this end, the Commission expanded to sixty-four members, calling in leading experts from established fields like biology, medicine, and theology. Alongside these specialists, the Commission placed a particular emphasis on engaging with the “new sciences of man” as the Pope referred to them: sociology, anthropology, psychology, and psychoanalysis. At the height of an apparent “sexual revolution”, the Church was opening its doors to secular, scientific thought in an attempt to combat its outmoded, anti-modern, and sexually repressive image.

Two years after its expansion, the Commission signed off on a majority report that suggested the Pope should change the Church’s teaching on artificial contraception. Leaked to the press in the spring of 1968, the report engendered an air of expectant optimism amongst much of the Catholic community. Infamously, Pope Paul rejected the Commission’s recommendation outright in his Encyclical letter, Humanae Vitae, published later that summer. The Pope’s pronouncement met widespread dismay and outrage both within and beyond the Catholic world. Many priests and laypeople left the Church altogether; many that remained chose simply to disregard the teaching. The Pope’s rejection, coupled with the limited source material available, has meant that the Commission’s internal workings have received little to no attention from historians of sex or Catholicism. However, the previously unpublished papers of this secretive body offer a valuable insight into changing Catholic understandings of human sexuality.

Central to the “liberal” Commission members’ case for change was a fluid, historically-contingent concept of sexuality. English theologian Rev. Charles Davis argued in a paper to the Commission that the meaning of sexuality was determined by cultural change rather than being a condition of nature:

“Sexuality cannot be understood as an isolated function or separate problem … It has a dynamic evolution, in other words a history.”

In accordance with this, the first line of the Commission’s final report read:

The Commission grounded its case for change in the same constructionist impetuses that were directing intellectual thinking in linguistics and the social sciences. It should be noted that this was ten years before Michel Foucault published his seminal work The History of Sexuality, which was to spawn a bevy of works contesting the historical specificity of “modern” sexual identities. Recognising the changing historical meaning of sexuality was a potentially groundbreaking moment for the Catholic Church, with consequences stretching well beyond the question of birth control.

If the Commission members established that sex was a subject to be studied and understood, what tools and apparatus did they use to measure it? Socio-scientific survey data and biological research were at the heart of how both female sexuality and contraceptive morality were constructed. British medical representatives Prof. John Marshall and Prof. John Cavanah carried out statistical surveys into “female sexual response,” contesting the virtues and limitations of various contraceptive methods. The newly introduced oral contraceptive pill and natural family planning, the only method of birth control approved by the Vatican, were two methods that particularly came under the microscope. Throughout all the Commission’s deliberations, female sexual pleasure was analysed within a coldly “empirical” framework of quantitative investigation. The complexities and contingencies of intimate sexual experiences were gauged by a series of yes/no questionnaire responses. Invariably, male intellectual “experts” interpreted these responses. What is notable by its absence from the papers of the Commission is a qualitative account of women’s everyday experience of sex. At no point were the women at the centre of this debate asked to talk about their own contraceptive choices, sexual sensibilities, or personal experiences.

In this sense, the Commission’s approach to sex was indicative of a broader intellectual climate in the middle of the 1960s. Following popular works of sex research like that of Masters and Johnson, sex became thought of as a biological phenomenon that could be measured in purely behaviourist terms. It was not until the start of the 1970s that intellectual approaches to sex underwent a paradigmatic shift, as social constructionists such as John Gagnon and William Simon began to show that sex was not simply driven by innate urges, but shaped by a complex set of social and cultural meanings. The Commission’s final case for contraceptive change was based on abstract theological argumentation, supported by “empirical” scientific evidence. There was no place for assessing the complex social and cultural meanings that constituted personal, sexual experiences. In this context, it is hardly surprising that the Pope responded in kind in Humanae Vitae – a rigidly intellectualised reiteration of doctrinal authority.

In the autumn of 2015, the Catholic Church’s teachings on sex, marriage, and the body came into focus once again with the gathering of The Bishop’s Synod on the Family. Real doctrinal change on contraceptive morality was not a major point of discussion, as indeed it has not been throughout Pope Francis’ apparently progressive premiership. The extent to which contemporary Catholic discussions about sex have been framed by the events of the 1960s continues to be a point of debate. Unlike the Commission, the Synod was not a secretive body, and this open approach is a testament to the Church’s recent efforts to distance itself from a poisonous tradition of sexual concealment. Once again, though, the embodied experiences of women were picked over by a collection of celibate men. While the Catholic Church has steadily begun to embrace the changing historical meaning of sexuality in the last sixty years, it remains reluctant to engage with the topic as a matter of subjective, personal experience. The full consequences of this approach remain to be seen. What is clear is that the relationship between the Church and contemporary sexual thought looks set to define the future of Catholicism, just as it did in the decades following Humanae Vitae.

David Geiringer has recently submitted his Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded PhD thesis on the sexual experiences of Catholic women in post-war Britain. He is an Associate Tutor at the University of Sussex. His teaching and research interests include the social and cultural histories of modern Britain, particularly the histories or religion and sexuality. He tweets from @DavidGeiringer

David Geiringer has recently submitted his Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded PhD thesis on the sexual experiences of Catholic women in post-war Britain. He is an Associate Tutor at the University of Sussex. His teaching and research interests include the social and cultural histories of modern Britain, particularly the histories or religion and sexuality. He tweets from @DavidGeiringer

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com