Interview by Dan Royles

Dagmawi Woubshet’s The Calendar of Loss (Johns Hopkins, 2015) examines the politics of mourning in the early years of the AIDS epidemic both in the United States and Ethiopia. The book details the ways in which early AIDS mourners used poetry, obituaries, visual art, and direct action protest both to commemorate loved ones and to challenge the apathy of a society that seemed all too willing to turn a blind eye to the epidemic. Throughout, Woubshet reads the work of black and white gay men alike through the lens of “black mourning” to draw out connections between AIDS activism and African-American culture, from the sorrow songs to Reagan-era hip hop. In this way, The Calendar of Loss places the experiences of black gay men, who have been hit hardest by the epidemic, at the center of the story of AIDS politics in the United States. For this contribution, The Public Archive recently named The Calendar of Loss one of its Top 10 Books of 2015.

Dan Royles: In The Calendar of Loss, you place black actors, some of whom may be unfamiliar to readers, at the center of the story, alongside more well-known figures like Keith Haring and groups like ACT UP. How is that different from other AIDS scholarship, and how does that change what we know about the early years of AIDS in the United States?

Dagmawi Woubshet: It is different from other literary and cultural studies of AIDS in that the experience of black gay men sits at the center of this book. In AIDS scholarship, and more generally in queer studies, black life is mentioned in passing or is an appendage or an exception to that of white gay people. The norm is to sum up the black gay experience in a paragraph or at most a chapter, a move I find suspect because it is a gesture really done out of pity and paternalism rather than serious intellectual engagement. My aim in this book was to tell the story of early AIDS art and activism without that kind of intellectual segregation and indeed, as you say, by centering black actors. In reconstructing the early years of AIDS, I already see a kind of whitewashing taking place, as if all the AIDS activists and artists were white, and that simply wasn’t the case. To give but two names, a group like ACT UP had among its rank and file key activists of color like Ortez Alderson, and the poetry of that era would be lacking without the elegies of Melvin Dixon. So, the book is both a way of centering the lives of black gay men who died of AIDS who shaped the era, and also a way of checking the impulse in AIDS and queer scholarship to render vanguards of the era as always and already white.

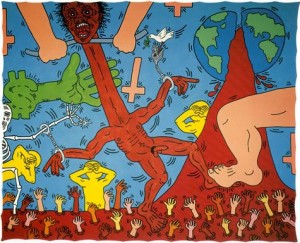

DR: You look at early AIDS mourning, including work by Paul Monette and Keith Haring, both of whom were white, through the lens of “black mourning.” What does black mourning illuminate about gay men’s experiences with AIDS in the United States across racial lines during the early years of the epidemic?

DW: The conceptual backbone of the book is a particular expression of loss that undergirds black life and cultural expression. Because of the modern invention of race, black people have had to contend with death that is both arbitrary and ubiquitous, and in response had to come up with a way of grasping in life and art the death-dealing character of America. From slave narratives to hip hop, there is the accounting of past deaths, as well as the anticipation of deaths that will come as early as tomorrow. So black art has developed a particular mechanism, a particular grammar and timeline of death, that reaches both backward and forward to express loss. That mechanism was also at work during the early era of AIDS when these young men—regardless of color—were witnessing the death of friends and lovers as well as their own impending death, and finding ways of expressing that kind of compounding loss. That’s why I look at the works of white artists like Paul Monette and Keith Haring through the lens of black mourning, since black mourning gives us the theoretical apparatus for thinking through compounding death. And why not? We apply, for instance, trauma theory to understand black life, even though trauma theory drew its examples and concepts initially from the Jewish holocaust. We also apply psychoanalytic theories of mourning and melancholia broadly to analyze loss across cultures, even though those theories were generated from a particularly European context. Given the insight and theoretical reach of black mourning, why not apply it widely to hail the experiences of those devastated by a mass catastrophe like AIDS? In many ways this conceptual move is in keeping with what I am doing by centering black actors to view the early era of AIDS: I am also centering a theory of loss generated within black life to theorize broadly early AIDS art and mourning.

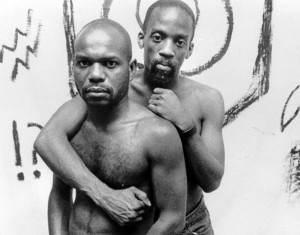

DR: You write about the “black queer counterpublic” forged by black gay artists and writers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including Essex Hemphill, Marlon Riggs, Melvin Dixon, Isaac Julien, Pomo Afro Homos, and Assotto Saint. What did that counterpublic look like? How was it different from the queer counterpublics created by ACT UP, Paul Monette, David Wojnarowicz, and others? (Or was it?)

DW: The story of a black gay renaissance in the 80s and 90s has yet to be fully told. It is only by way of the AIDS crisis that that story appears in The Calendar of Loss. I am astonished by the number of black gay collectives and publications that appeared during this period. What made that counterpublic different was that it addressed two different publics from which it was—and remains—excluded: a black public where queer life was and is marginal, and a white queer public where black gay life was and is marginal. In the papers of a collective like Other Countries, anthologies like In the Life and Brother to Brother, films like Tongues United and Looking for Langston, to name just a few, there is a three-fold imperative. One, to assert publicly a black gay identity, and show how race and sexuality are inextricable. Two, to reclaim the imbricated shame attached to blackness and queerness. And three—and most key—to cherish and relish in the riches of black gay culture born out of these margins. Snap! Snap! Snap! Of course, there are overlaps. For instance, Assotto Saint, a central figure of this renaissance, also participated in many an ACT UP demonstration, and Bill T. Jones collaborated not only with Marlon Riggs, but also Keith Haring on many occasions. So we have to be mindful of the collaborations and friendships, the flow of ideas, across the color line, while mindful of the particular prerogative of a black queer counterpublic that emerged at the time.

DR: How did you decide on the structure of the book and the subject of each chapter? Was there anything interesting that you had to cut, or couldn’t find a way to make fit?

DW: The book is loosely structured around the conventions of mourning. Funerals anchor the introduction; elegies, the first chapter; obituaries, the second; icons of the dead, the third; and epistles to the dead, the last chapter. Ultimately, my argument is that the body of mourning produced during the early era of AIDS has fundamentally altered these prized conventions of grief. There is a chapter that I had to cut out, which compared AIDS discourse in apartheid South Africa in the 1980s and post-AIDS discourse in the U.S. in mid-to-late 1990s. Hopefully, I will return to that comparison at some point because there is an uncanny similarity to how whiteness came to the rescue of white gay men in apartheid-era South Africa and post-HAART America. In both contexts, whiteness helped to remove the specter of AIDS away from the (white) gay community and place it on people of color. But that chapter was more of a critique of a discourse and not an analysis of the art of mourning, and interrupted the flow of the book structured around conventions of grief.

DR: You write in the preface to The Calendar of Loss about your personal connection to the stories within, whether as a black gay man in the United States, or as someone who lost childhood friends to the Ethiopian AIDS epidemic. How was the emotional experience of writing this book?

DW: That’s hard to sum up. I grew up in the shadow of the AIDS crisis and have lost friends dear to me. I also came of age reading people like Melvin Dixon and Paul Monette, who gave me the key to deal with my own sexuality. No doubt about it, this was a personal and emotionally charged project. In hindsight, more than the writing, it was the research that took its emotional toll, because it revealed to me how vast the devastation was, how gross the indifference and hatred directed towards gay people. I spent months at the New York Public Library reading the obituary columns of The New York Native and The Washington Blade, and weeks at the Schomburg library going to through the papers of Assotto Saint, which are brimming with so much loss. That was taxing. Emotionally, that kind of daily encounter with the archive was perhaps the most difficult. The writing was also difficult, but in a different way. It was more demanding than difficult because although it is a scholarly book, with some intricate theoretical claims, I have tried to use prose that has fidelity to the pathos of the grief I am examining. I didn’t want to diminish the sorrow of these works with lifeless academic jargon, so I had to go through many edits to get the language right. I am not sure if I have succeeded all the way, but I have tried very hard.

DR: The Calendar of Loss and the “poetics of compounding loss” that you describe call to mind Black Lives Matter and the shape that movement has taken over the last year and half. As someone who has thought a lot about black mourning, how do you read Black Lives Matter?

DW: I read Black Lives Matter both in its own time and in the broader context of black activism born out of death. One of the pivot points of the modern civil rights movement was the killing of Emmett Till and the photograph of his totally disfigured body lying in an open casket. That image exposed America for what it was: a country with an insatiable appetite to maim and kill black people, including children, and do so with impunity. That image galvanized the Civil Rights Movement. So, black death, whether in the age of slavery or Jim Crow lynching, has been a catalyst for activism, and the slogan “black lives matter” has been iterated in one way or another since we have had black people on these shores. And, along with black lives matter, the other clarion call is black death matters. When I think of the shooting of Michael Brown, I am outraged not only by the killing itself, but also the way his body was treated, allowed for hours to cook on the ground in the sun, without any care accorded to the corpse. I’m reminded of a line in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: “It was a common saying among little white boys that it is worth a half-cent to kill a nigger and a half-cent to bury one.” Over the arc of black history, the twin notions that black lives matter and that black death matters have been a conjoined cry and call for activism, even revolution. Even in the 1980s, as I discuss in the book, the barbaric killing of Michael Stewart in the hands of police echoes exactly what’s unfolding today. The difference is that the series of deaths are being captured on tape and the country—to be specific, white America—is made aware of how pervasive the arbitrary killing of black people remains to this day. I don’t mean to be cynical, but I doubt that this new awareness will fundamentally change the attitudes of white America. What matters, at least to me, is that Black Lives Matter has galvanized a new generation of Americans, of all colors, to reckon with the unjust ways in which black people are treated in this country. One must hope that this renewed energy will impact the structure of power somehow.

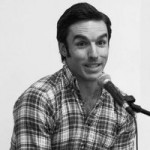

As a scholar of African American literature and culture, Dagmawi Woubshet works at two pivotal intersections, between African American and sexuality studies, and between African American and African studies. These overlapping areas of inquiry inform his scholarship and research, including his book, The Calendar of Loss: Race, Sexuality, and Mourning in the Early Era of AIDS (Johns Hopkins University Press, Spring 2015). Woubshet is the co-editor of Ethiopia: Literature, Art, and Culture, a special issue of Callaloo. His work has also appeared in Transition, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Art South Africa, and African Lives: An Anthology of Memoirs and Autobiographies. In 2010, he was named a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum, and his other honors include a faculty fellowship at the Institute of Ethiopia Studies at Addis Ababa University in 2010-11, and the Robert A. & Donna B. Paul Award for Excellence in Advising in 2012. In 2014, he was named one of “The 10 Best Professors at Cornell.” He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University and his B.A. from Duke University.

As a scholar of African American literature and culture, Dagmawi Woubshet works at two pivotal intersections, between African American and sexuality studies, and between African American and African studies. These overlapping areas of inquiry inform his scholarship and research, including his book, The Calendar of Loss: Race, Sexuality, and Mourning in the Early Era of AIDS (Johns Hopkins University Press, Spring 2015). Woubshet is the co-editor of Ethiopia: Literature, Art, and Culture, a special issue of Callaloo. His work has also appeared in Transition, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Art South Africa, and African Lives: An Anthology of Memoirs and Autobiographies. In 2010, he was named a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum, and his other honors include a faculty fellowship at the Institute of Ethiopia Studies at Addis Ababa University in 2010-11, and the Robert A. & Donna B. Paul Award for Excellence in Advising in 2012. In 2014, he was named one of “The 10 Best Professors at Cornell.” He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University and his B.A. from Duke University.

Dan Royles is a visiting assistant professor of history at Florida International University. His first book, To Make the Wounded Whole: African American Responses to HIV/AIDS, is under advance contract with the University of North Carolina Press. He is also working on an oral history project and digital archive dealing with the history of African American AIDS activism. Follow him on Twitter @danroyles.

Dan Royles is a visiting assistant professor of history at Florida International University. His first book, To Make the Wounded Whole: African American Responses to HIV/AIDS, is under advance contract with the University of North Carolina Press. He is also working on an oral history project and digital archive dealing with the history of African American AIDS activism. Follow him on Twitter @danroyles.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com