Interview by Justin Bengry

Yorick Smaal’s recent book Sex, Soldiers and the South Pacific, 1939-45: Queer Identities in Australia in the Second World War (Palgrave, 2015) looks to the dynamics of wartime to consider how sex and sexuality was affected by global conflict. Massive influxes of American servicemen transformed sexual communities, and even language, in Australia. Sexual fluidities still characterised queer communities and male identities before a more rigid sexual binary emerged later in the century. Smaal’s work offers not only an exciting local study, but one inflected by global processes, challenging us to think of queer history in the most expansive of terms.

Justin Bengry: How would you characterize queer identities and communities in Australia before the Second World War?

Yorick Smaal: An urban queer lifestyle was only beginning to mature in Australia by the 1920s and 1930s. The mollies familiar to London’s streets during the eighteenth century did not migrate to the hostile environment of the colonies, even if we occasionally glimpse exceptional cases of flamboyancy in the early records. It is not until the 1890s that queer subcultures began to develop with any level of sophistication in larger Australian cities. By the interwar years, men were meeting for sex and sociability in working-class bars, cafés, cinemas and sometimes in social groups. Intimate parties brought men together in female dress, powder and paint. Others formed relationships on the job. Queer opportunities and possibilities for intimacy, romance and friendship were evident in large urban department stores, for example, especially among the window dressers, tailors and floorwalkers.

Things were less sophisticated beyond the confines of capital cities like Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. In regional towns and rural areas interaction was probably limited to intimate partners and perhaps the odd friend, although the circulation of men and ideas between the city and bush meant that regional Australians were not unfamiliar with queer ways of being and doing.

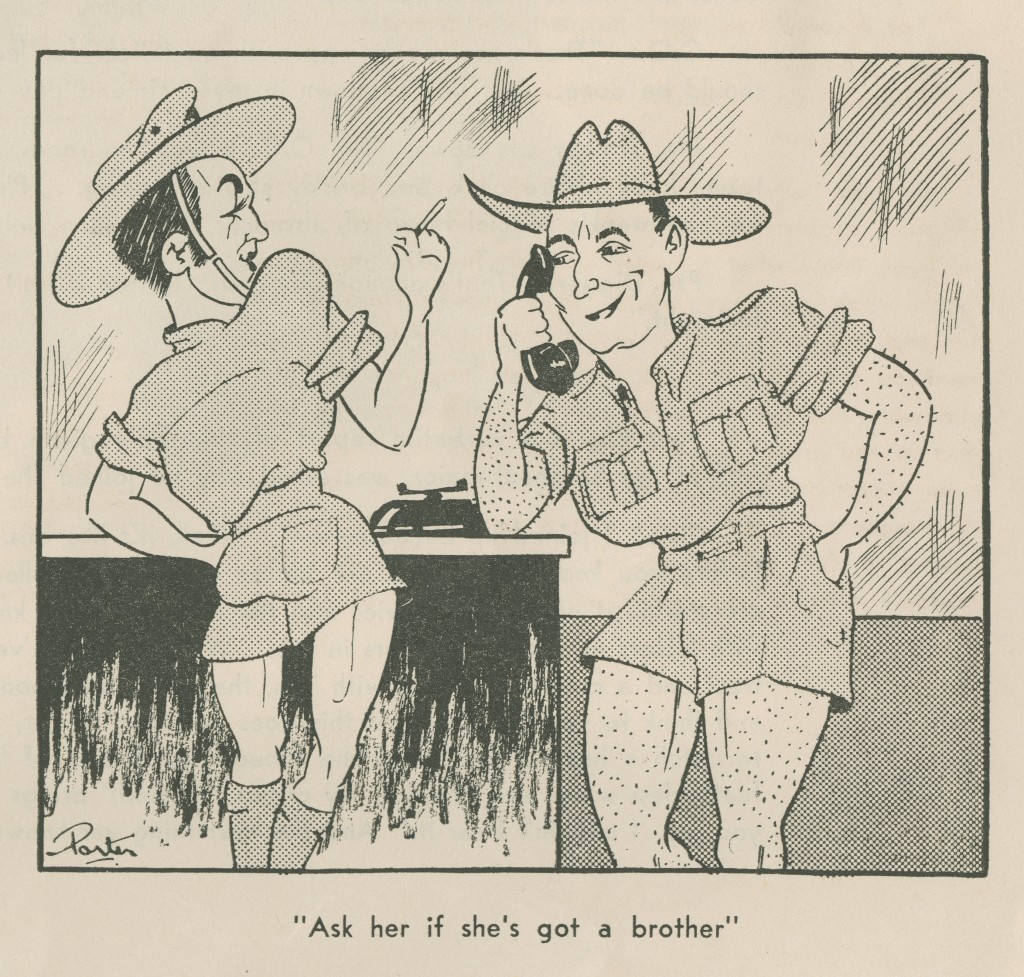

Gender inversion was the central thread in queer identities and self-presentation by the time the Second World War erupted, at least for working-class men (we know little of middle-class lives). Self-described cissies and queens adopted feminine traits and performed gendered cultural ceremonies. Some ‘carried on’ in the streets of Brisbane mocking each other in coded ways even in public. Others were married to each other in elaborate ceremonies of revelry, merriment and carnality. Sexual passivity usually accompanied ‘female’ identities, but not always. One of the points I’ve stressed in the book is that these gendered lives were self-generating and self-sustaining. Given that masculine ‘butch’ men in Australia were discreet, circumspect and only occasionally interested in homosex, queer men often relied on each other to adopt a ‘male role’ in intercourse even if their preferences lay elsewhere.

JB: How did American understandings or experiences of queer sexualities differ from Australians’ at this time?

YS: Australian and American lives shared similarities and differences during the Second World War. Queer men were subject to state interdiction and moral outcry regardless of nationality, and queerness varied across class, ethnicity and geography. Generally speaking, life in large US cities was richer than the Australian experience given the economies of scale. Exclusive gay bars, for instance, can’t be dated earlier than the 1960s in Australia, decades after they began in the US. Different terminologies point to different sexual economies. Non-gendered middle-class queer identities in the US (where some men began to dissociate their gender roles and sexual identities) prefigure Australian equivalents. Camp, or kamp, didn’t really even develop in Australia until the end of the 1930s.

There were also variations among the attitudes and practices of medical experts and military commanders during the war. Psychiatrists in the US had a head start on their Australian counterparts who struggled to find legitimacy in the local context, while the American forces focused on homosexuality in a way that Australian officers did not. The US army and navy set in place a range of policies to discharge queer personnel administratively; the Australian army buried its head in the sand and wished the whole thing would go away.

JB: What impact did the influx of American soldiers have on queer Australians?

YS: The arrival of Americans from late 1941 altered the lives of queer men as it did for other Australians, especially in Queensland, where much of my story is set. As a major staging and supply base Queensland felt the social and military effects of massive numbers of US personnel more than any other state. The capital, Brisbane, a garrison city, was tagged ‘the American village’. Visitors introduced new experiences to local populations. Novel styles of music and dance soon caught on.

Well-mannered, smartly dressed and affluent men in uniform attracted the attention of both sexes, and men and women competed for American affections. The sheer scale of the US presence affected the pace of local queer worlds – at parties, at bars and hotels, and at public cruising areas, there were many possibilities for rendezvous. That said, cultural exchange went in both directions. Life in Australia shaped the experiences of young US soldiers, too. Discovering romance with locals on distant shores provided comfort and support to homesick servicemen facing long deployments and the dangers of conflict.

Queer American visitors fitted into local worlds and shared information with new friends and lovers on life back home and in the US forces; a new language emerged with their arrival. Terms like ‘fruit’, ‘queer’ and ‘blowjob’ all appeared in the Australian lexicon in the 1940s, the latter reflecting an alleged fondness among GIs for fellatio.

Some men formed strong emotional bonds that cut across national borders. They stayed in touch when soldiers were redeployed as the war marched forward, communicating even after victory was declared. Lovers made plans to stay together after the war and others visited friends for decades. Still, I’ve been cautious not to underplay tensions or romanticise this encounter and exchange. Some Australians pointed out American visitors were only interested in sex rather than the relationships that they wanted, while US troops were not always enamoured of their antipodean comrades. Even different accents could be a turn-off for some individuals.

JB: Was Australia unique compared to other areas of wartime mixing and disruption?

YS: No, I don’t think so. Disruption, displacement, dislocation and war go hand-in-hand. Australia wasn’t distinctive in that regard. The American presence was felt in wartime France and around one and a half million GIs were stationed in, or passed through, the UK by the war’s end. In these places too, visitors were met with curiosity and resentment. Australia’s exceptionalism lay in the relative scale of the American influx compared to the size of the local population and the tyranny of distance that magnified that experience.

JB: Your book weaves references to significant incidents in New Guinea and Noumea, New Caledonia, throughout several chapters. Can you summarize the significance of these locations?

YS: Port Moresby and Noumea were important ports and forward bases in the battle against the Japanese. Port Moresby handled large volumes of shipping and supplies and staged and despatched Allied personnel. Noumea was a major naval base hosting the largest number of Americans in the region outside Australia. The eventual US force there numbered some 40,000 troops.

If we find a few closely knit networks of friendship and sociality in smaller military outposts, service personnel created vibrant cultural worlds in larger forward bases. Along with plenty of situational relief, gendered worlds rivalling those on the home-front emerged among in logistical staging zones. Soldiers managed to find like-minded companions amongst the jumble of men coming and going, the staging camps and military supplies and equipment. A group of Australian soldiers, who called themselves ‘girls’, operated among Allied soldiers in Port Moresby and in Noumea, some 1200 kilometres away, American sailors known by female names and pronouns formed discrete social groups.

Soldiers and sailors organised outrageous queer parties and intimate get-togethers, they formed dense networks of friends and lovers, and they cruised for sex among the throngs of ‘normal’ men. More experienced men, or ‘Aunties’, took initiates under their wings. Some men affirmed their sense of self in these all-male worlds while others discovered unrecognised or suppressed longing.

Bases like Port Moresby and Noumea formed part of a wider network of knowledge and practice, distributing attitudes, ideas and practices. Some men applied new behaviours in the civilian world, and the presence of gender inversion in the forces shouldn’t be underestimated. Queer life on these bases was important for commanders too, especially those in the Australian army. They reluctantly tackled the problem only after US colleagues in New Guinea advised them in late 1943 that a number of Australian men practiced ‘the female side of homo-sexual intercourse’.

JB: How does your story contribute to recent studies in queer history that challenge the stability of sexual identities before the 1960s, arguing that fluidity instead characterised many men’s sexual experiences, particularly working-class men?

YS: The war provided a massive boost to gendered identities in a way that would not have happened otherwise. Large numbers of dislocated young men created a ‘butch’ cohort willing to engage with ‘cissies’. This is especially important in Australia where ‘normal’ men were more circumspect and discreet in seeking out same-sex intimacy or accepting queer advances. Fluidity was prevalent in the forces, as is often the case with same-sex institutions. Military life brings with it degrees of emotional and sexual intimacy. Normally private functions were conducted publicly as men bathed, ate, slept, worked and fought together. The scale of the war – almost 1 million Australian men and 16 million Americans – meant that servicemen had a profound impact on the wider civil world as well.

There was also a certain amount of instability between queer lives and identities. Everyday realities mean that people’s experiences and interests didn’t neatly comport to one set of rules. Not all kamp men were respectable and private; not all queens and cissies were passive. The evidence reveals a complex mix of self-confidence and self-doubt, sexual behaviours and identities, languages and cultures that shifted as people encountered new experiences and ideas. These discoveries occurred in a range of settings where men made and remade the self in public and private.

JB: Whose stories were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

YS: It’s always difficult to choose case studies and examples, especially when you’re fortunate enough to strike a rich vein of evidence. My primary focus on Australia meant that I couldn’t include as many American stories as I wanted to. I’ve collected numerous life stories of US sailors that stretch back to the 1920s and 1930s, as well as courts-martial on queer experiences in the forces and the circumstances of policing and prosecution. Their exclusion has been serendipitous – these stories now form part of a new long-term project I am working on.

Other stories I wanted to tell were frustrated by the sources. A central homosexual discharge file for the army, the largest of the Australian forces, meant much of my attention and analysis focussed on that branch of service, with less comment on sailors and airmen although they occasionally appeared before the civil courts. Australian non-Anglo ethnicities and First Peoples were especially difficult to weave into the text because the records don’t reveal their experiences despite a legacy of racial difference in North Queensland and thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders serving in the forces.

The American files too are largely silent on the lives and loves of black men despite their richness elsewhere. Despite heavy surveillance of the black presence in a white Australia, most of the official concern was directed towards the protection of women and children, obscuring experiences of same-sex intimacy. The extant evidence suggests that they tended to keep to themselves or their own networks, although inter-racial relationships are occasionally recorded in diaries like those of the queer Australian soldier and official wartime artist, Donald Friend.

JB: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

YS: The book’s use in the classroom all depends on the topic and objective. It might be useful for a course on global sexualities and genders, providing different perspectives in an area often dominated by American and European experiences. Those teaching Australian history will probably find the military chapters (‘Men in uniform’ and ‘Confused Commanders’) especially useful given the paucity of work on queer experiences in the forces. On the complexities and patterns of male desire, the book could be read alongside George Chauncey’s Gay New York or Matt Houlbrook’s Queer London; for studies on war and society, with work by Emma Vickers, Allan Bérubé or Paul Jackson. Thematic chapters on sexual geographies, policing, and medicine might provide complementary perspectives to other work in these areas.

I wanted to emphasise the agency and expression of queer lives and queer worlds. Many men enjoyed a happy and contented existence despite social expectations, moral strictures and the looming threat of criminal law. Individuals lived their lives free from state interference and they rejected or modified dominant narratives that cast them as outlaw, mentally unwell and prey to vice. Of course, some individuals were more fortunate than others. Ironically it’s those men whose lives collided with the state that often provide us with the richest evidence of past experiences.

Yorick Smaal is an ARC DECRA Research Fellow at the Griffith Criminology Institute, Griffith University. He is a social historian with interests in sex and gender, war and society, and law and criminal justice. Yorick is book review editor of Queensland Review and is also author and editor with Graham Willett of Out Here: Gay and Lesbian Perspectives VI (Monash University, 2011) and Intimacy, Activism and Violence: Gay and Lesbian Perspectives on Australasian History and Society (Monash University, 2013).

Yorick Smaal is an ARC DECRA Research Fellow at the Griffith Criminology Institute, Griffith University. He is a social historian with interests in sex and gender, war and society, and law and criminal justice. Yorick is book review editor of Queensland Review and is also author and editor with Graham Willett of Out Here: Gay and Lesbian Perspectives VI (Monash University, 2011) and Intimacy, Activism and Violence: Gay and Lesbian Perspectives on Australasian History and Society (Monash University, 2013).

Justin Bengry is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow on the project Queer Beyond London at Birkbeck, University of London and researcher on the Historic England LGBTQ heritage and mapping project Pride of Place. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Queer Profits in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

Justin Bengry is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow on the project Queer Beyond London at Birkbeck, University of London and researcher on the Historic England LGBTQ heritage and mapping project Pride of Place. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Queer Profits in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com