Nell Haynes and David Aruquipa Pérez

In the mid-1990s, David Aruquipa Pérez attended the opening of a new gay bar in La Paz, Bolivia. But before the festivities could begin, police raided the bar with the excuse that there had been reports of drug use. Aruquipa knew that many Bolivians saw non-heteronormative individuals as representatives of a seedy subculture, awash in drugs, defying all religious and community norms, and wholly unlike anyone in their families or circles of friends. After this incident Aruquipa decided, “we cannot continue to be victims of this kind of repression,” and began his life as an activist. He and other Bolivian activists have focused their efforts on bringing visibility to sexual and gender diversity in Bolivia, hoping this visibility will lead to increased social acceptance and political representation.

Recent commentaries and scholarship, particularly among queers of color and LGBT immigrants in U.S. contexts, has problematized the increased visibility associated with “coming out.” But this reluctance toward visibility does not carry equal weight among activists in such post-colonial contexts as Bolivia. Gender and sexual diversity activists in Bolivia instead suggest that visibility grants them a social positioning from which to contest public imaginaries of LGBTI people (Locally Gay, Lesbiana, Bisexual, Transexual, Transgénero e Intersexual; though at times written as TLGB referring to Trans, Lésbico, Gay y Bisexual) as monstrous deviants who are Satanists and drug addicts that are actively destroying society. By promoting a public presence, they hope to change societal norms and gain access to resources and rights.

In Bolivia today, race, class, education, religion, urban/rural residence, citizenship, and political affiliation inflect the diversity of identities related to gender and sexuality. Of course, these different strands of identification are not entirely independent, but are correlated so that upper-class individuals are often more “white,” well educated, and support political parties aligned with neoliberal policies. Those of the popular classes are understood to be mestizo or indigenous and, particularly in the last decade, are more closely aligned with socialist political parties. As we see in much of the world, the acceptability and visibility of different identities of the LGBTI spectrum are conditioned by these other racial/classed formations. While upper class individuals who occupy forms of sexual diversity usually categorize themselves as “gay” or “lesbiana,” and often connect this identity to a sense of being “moderno” (modern) and cosmopolitan, popular-class individuals more often understand gender non-normativity as central to their identities. Though specific categories and forms of identifying have changed over time, Bolivians have always understood their gender and sexuality in ways that articulate with class, race, and rural or urban lifestyles, political affiliations, and other social categories.

Prior to the 1950s, the very names by which individuals outside of normative sexual practices and gender presentation were known relied on an intersectional understanding of race, class, urban/rural location, and other factors. Mestizo men from prominent families who fell outside of heteronormative expectations were most often referred to as maricas (sissies or fags) or mariposas (butterflies). These ways of naming highlighted their gender presentation rather than making explicit their sexual preferences or practices. Indigenous men, who were most often non-citizen peon hacienda workers, also expressed non-normative identities through gender non-conformity, and were often called q’iwa (Quechua, two spirit people). At this time, women’s sexual diversity received very little public acknowledgement and was assumed by many to be nonexistent. So even the categories through which an individual’s gender or sexual diversity might become visible were highly structured by their gender, race, ethnicity, class, and other social positions.

The Agricultural Revolution of 1952 brought about a massive restructuring of Bolivian society. Indigenous people gained full citizenship, but at the same time official discourses erased their ethnic affiliation by shifting them from the racialized category of “Indio” (Indian) to the class-based category of “campesino” (peasant). Chicharias, localities for drinking chicha, a beer made from fermented corn, became important politicized spaces aligned with social mobilization of marginal populations, combining the popular classes (including campesinos), organized labor advocates, immigrants, and cholas (urban indigenous market women known for being politically active), gender diverse people, and even progressive government officials. Through the space of the chicharia, understandings of gender diversity were closely tied to other forms of progressive politics.

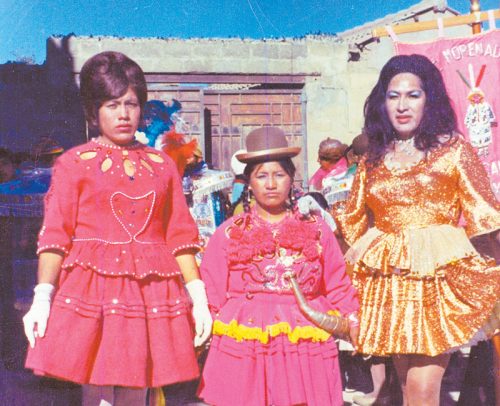

But chicharías were somewhat private spaces, and many gender-diverse Bolivians hoped for more public visibility. Men often sought out involvement in the arts, and became involved in music and popular festivals where they danced in women’s roles. They began dancing in the role of “China Morena”—a flirty feminine character in the Morenada festival dance—as a form of institutionalizing and giving public visibility to cross-gendered and cross-dressing practices. They also saw this as an important way of connecting with international movements such as those that grew out of the Stonewall riots of 1969 in the United States, and similar movements in Mexico and Argentina. But rather than fomenting a movement through protest and violence, they did so through popular culture and the arts. In common Bolivian parlance, “they waited for the festival to make a revolution.”

The growing HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s shifted global attention to sexual practices between men, including in Bolivia. The first case of HIV in the world was recognized in 1984, and in 1986 the first case was diagnosed in Bolivia. In the early 1990s, Bolivian activists formed groups dedicated to issues related to HIV/AIDS and human rights: Cochabamba’s Grupo Dignidad in 1992; Santa Cruz’s Unidos en la Lucha por la Dignidad y la Salud (UNELDYS) in 1993; and La Paz’s Movimiento Gay La Paz (MGLP) in 1994. HIV advocacy marked a new course for sexual diversity activists and oriented the collective view more toward public health than political rights or ideological views on gender diversity. These were the first steps toward participating in institutional structures specifically as sexually diverse people, and many groups in Bolivia still maintain this institutional framework of public health.

These approaches were not without critique, as many Bolivian groups aligned with international agendas focusing on gay men’s health rather than including other forms of sexual diversity. Mujeres Creando (Women Creating), a leading feminist voice in La Paz since 1992, decried the invisibility of lesbians in the HIV/AIDS focus. They pointed out that this invisibility continued the legacy of erasing same-sex-identified women from public discussion since before the 1950s. They set their own agenda, envisioning an alliance between “indias, putas, y lesbianas” (Indians, whores, and lesbians), terms whose incendiary nature is employed intentionally and strategically, in revolting against patriarchy.

Other groups focusing on transgender, travesti, and cross-dressing individuals were formed in Santa Cruz (1996), La Paz (1997), and Cochabamba (1999). These groups were especially concerned with forms of violence against travestis, including violence perpetrated by police. Public visibility was an important point of organizing across many of these groups, including the Familia Galán (Galan Family) in La Paz, a group who began putting on drag performances in public spaces in 1997 in order to increase the visibility of gender diversity in La Paz. Most of these nascent groups supported the first “transformista” (transgender) beauty pageants in the late nineties, which worked toward claiming public space and political rights for sexually and gender diverse Bolivians. The late nineties was also a transformational moment as meetings in Santa Cruz (1995), Yacuiba (1996), Cochabamba (1997), and finally a national congress in La Paz in 1998 helped consolidate a national movement for gender and sexual diversity rights.

The beginning of the Twenty-First Century was a time of great political turmoil in Bolivia, during which TLGB Bolivians stood alongside working class and indigenous individuals in protesting against the neoliberal policies of President Sánchez de Lozada. Sánchez de Lozada resigned in 2003, and shortly thereafter, Bolivians elected their first indigenous-identified president, Evo Morales. Though Morales has been known to disparage gays, gender non-conforming individuals, and even women in his public remarks, many LGBTI Bolivians were involved in the assembly convened to write a more inclusive constitution, and attempts to widen the Morales government’s political agenda.

Most recently, Bolivia has made news with a May 2016 law allowing individuals to more easily change the gender with which they are identified in official documents. The bill was supported by Morales’s vice president, Álvaro Garcia Linera, who suggested it rectified previous lack of acknowledgement for TLGB individuals. Yet Paris Galán, a prominent member of Familia Galán, spoke out suggesting that Congress only approved the law to quell activists’ ire over Morales’s derogatory remark implying that the health minister, a single woman, must be a lesbian. In the year during which the law has been in effect, religious organizations and other conservative groups have connected the law to what they call ideología de genero (gender ideology), which is associated with atheism and framed as a “rebellion of the created against its condition of creation [by God].” The rhetoric against “gender ideology” has been strong throughout Latin America, and demonstrates the need for continued activism aimed at greater understanding and visibility for sexual and gender diverse individuals in the region.

This history belies the ways that, like in all contexts, political allegiances and competing priorities—often among visibility, legislation, and health—have shaped movements for equality for LGBTI Bolivians, and thus, their histories. To be sure, factions and criticisms still exist among different groups advocating for equality among people with diverse identities related to gender and sexuality. However, visibility provides a point of convergence, as Mujeres Creando has sought to combat the erasure of lesbians, the Familia Galán brings gender play into public spaces, current legislative activists make visible individuals’ preferred gender identity on government documents, and the very publishing of books such as Memorias Colectivas and La Virgen de los Deseos advance a radical politics of visibility in a country often invisible to the rest of the world.

Nell Haynes is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Linguistic Anthropology at Northwestern University. Her research addresses themes of performance, authenticity, globalization, and gendered and ethnic identification in Latin America. She earned her Ph.D. in Anthropology at American University in 2013 with a concentration in Race, Gender, and Social Justice. Nell is author of Social Media in Northern Chile (2016), and has published on gender, sexuality, and race in Bolivia in a number of journals, edited volumes, and co-authored books. Nell is currently working on a book project titled Chola in a Choke Hold: Remaking Indigeneity through Bolivian Lucha Libre.

Nell Haynes is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Linguistic Anthropology at Northwestern University. Her research addresses themes of performance, authenticity, globalization, and gendered and ethnic identification in Latin America. She earned her Ph.D. in Anthropology at American University in 2013 with a concentration in Race, Gender, and Social Justice. Nell is author of Social Media in Northern Chile (2016), and has published on gender, sexuality, and race in Bolivia in a number of journals, edited volumes, and co-authored books. Nell is currently working on a book project titled Chola in a Choke Hold: Remaking Indigeneity through Bolivian Lucha Libre.

David Aruquipa Pérez is a human rights activist, Familia Galán member, current president of Colectivo TLGB of Bolivia, and president of the Board of Directors of Comunidad Diversidad. David is also author of several books, including La China Morena: Memoria Hístorica Travesti, and co-authored Memorias Colectivas: Miradas a la historia del Movimiento TLGB en Bolivia [Collective Memories: A Look at the History of the TLGB Movement in Bolivia], with Paula Estenssoro Velaochaga, and Pablo C. Vargas.

David Aruquipa Pérez is a human rights activist, Familia Galán member, current president of Colectivo TLGB of Bolivia, and president of the Board of Directors of Comunidad Diversidad. David is also author of several books, including La China Morena: Memoria Hístorica Travesti, and co-authored Memorias Colectivas: Miradas a la historia del Movimiento TLGB en Bolivia [Collective Memories: A Look at the History of the TLGB Movement in Bolivia], with Paula Estenssoro Velaochaga, and Pablo C. Vargas.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com