In early August, 1900, the trustees of the British Museum (which housed the British Library until 1997) received extremely exciting news. One of the leading businessmen of London, who had just passed away, had left the library an incredibly generous bequest. The donation was rumoured to number hundreds or thousands of books, including the world’s largest collection of Don Quixote manuscripts and Cervantes material. The collection included first editions, unique imprints, and original Cervantalia. But the material came with a catch.

The British Museum would only be awarded possession of the priceless collection if it also agreed to take another of more … specialist interest. Over the course of the day, the trustees’ eagerness would have turned first to foreboding and then absolute horror as they reviewed the other material they had to accept. Hardly high literature, it included such suggestive paragraphs as,

The sight of our red smarting bottoms and bursting pricks was too much for Annie and Rosa, and they were inflamed by lust, so throwing themselves backward on the bed, with their legs wide open and feet resting on the floor, the two dear girls presented their quims to our charge, as with both hands they held open the lips of their delicious cunts, inviting our eager cocks to come on.

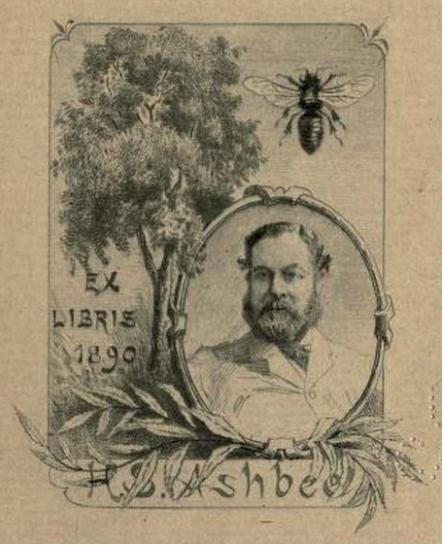

The remarkable owner of this priceless and obscene material was none other than Henry Spencer Ashbee. He was, on the surface, a reputable and successful Victorian gentleman. On further examination, however, he emerges as the stereotypical Victorian gentleman with a dirty secret in his closet. Born in 1834, Ashbee married into the somewhat successful textile manufacturing company Charles Lavy & Co., and went on to make his fortune in the booming pre-war Victorian economy. He quickly made a name for himself with his fluency in Greek, Latin, several other modern languages, and his absolute mastery of Spanish. Indeed, he later became a prominent Spanish literary critic. By the middle of his life, however, he began to use his skills for a secretive and obsessive hobby—book collecting, specifically, erotic book collecting.

Ashbee fixated on creating one of the most extensive erotic book collections in England, if not the Western world. Moreover, as Ian Gibson argues, there is a good chance that Ashbee was the author of the infamous multi-volume pornographic autobiography, My Secret Life. The Obscene Publications Act of 1847 had failed to have any measurable impact on the trade in illicit writings. Only a decade later the Saturday Review reported that “the situation was as bad as ever”, and that “the dunghill is in full heat, seething and steaming with all its old pestilence.” Indeed, there was a veritable explosion of pornography in England and the United States. Visitors to the usual book-buying neighbourhoods or behind-the-counter newsstands could select from such titles as; Intrigues in a Boarding School (1860), Confessions of a Lady’s Maid (1860), How to Raise Love or The Art of Making Love, in more ways than one (1863), Lucretia or the Delights of Cunnyland (1864), and many other variations on these themes.

By the 1870s and 1880s discriminating buyers could even buy material from pornographic subgenres: boarding school, virgin confessions, incest, nunneries, sex guides, flagellation—each with their own standard plots and tropes. Something about this proliferation of material held a spell over a certain cast of characters in British society. Men like Ashbee gathered into secret clubs and associations such as the Cannibal Club to read, love and collect this material. Like many other rich businessmen, Ashbee went so far as to maintain a private apartment in London, but this apartment wasn’t for his mistresses, it was filled with bookshelves creaking under the weight of his illicit books.

Looking around, in his early 40s, Ashbee decided to contribute his own pen to the preservation and glorification of his obsession and decided to write a trilogy of Indexes of erotic literature. In his first Index, Index Librorum Prohibitorum, published in 1877, he described his reasons for doing so:

That English erotic literature should never have had its bibliographer is not difficult to understand. First and foremost the English nation possesses an ultra-squeamishness and hyper-prudery peculiar to itself, sufficient alone to deter any author of position and talent from taking in hand so tabooed a subject.

Ashbee was profoundly disturbed by what he saw as the backwards sexual morality and ‘hyper-prudishness’ of English and American society at the time. As a result, many of his excerpts are the only surviving record of some books. For example, the entry for Intrigues in a Boarding School provides bibliographical details about the book, summarized it, and concluded that “these dialogues are put together without any art, and the volume is valueless from a literary point of view.”

Even though Ashbee had managed to squirrel away a massive library, he wrung his hands at how so many erotic novels had been lost to “hyperprudishness,” and was well aware that even his own collection might be lost to history. This fear of loss led him to a clever plan: when he died, he offered both the erotica and the world’s largest collection of Cervantes materials, manuscripts, and Don Quixote engravings, on the condition that the British Museum take all of it (excepting duplicates) or none of it. The museum, trapped in this way, decided there was nothing to be done, and that their desire for the Cervantes material outweighed their squeamishness at the pornography.

The Ashbee collection went on to form what was called the Private Case of the British Library for a number of years until it was opened up to the general public and researchers in the late 1960s, and the more ‘offensive’ ones not until the 1990s. Both Ashbee’s bibliography and his private collection have proved a tremendous boon to researchers of material that is too often missing. In a strange way, one man’s monomania has become everyman’s resource. Undoubtedly Ashbee would be immensely pleased to know that his catalogues are still being used today, despite every indication that they too would be lost.

Brian Watson is a historian of pornography and obscenity and is especially interested in the interactions of private and public sexuality. He is the author of Annals of Pornographie: How Porn Became Bad and upcoming chapters on the history of obscenity. Brian has taught at New England College and elsewhere. He has appeared on Conan O’Brien among other locations, and he is the co-host and editor of the AskHistorians podcast. He is a graduate of Drew University’s Caspersen School. He tweets from @HistoryOfPorn.

Brian Watson is a historian of pornography and obscenity and is especially interested in the interactions of private and public sexuality. He is the author of Annals of Pornographie: How Porn Became Bad and upcoming chapters on the history of obscenity. Brian has taught at New England College and elsewhere. He has appeared on Conan O’Brien among other locations, and he is the co-host and editor of the AskHistorians podcast. He is a graduate of Drew University’s Caspersen School. He tweets from @HistoryOfPorn.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com