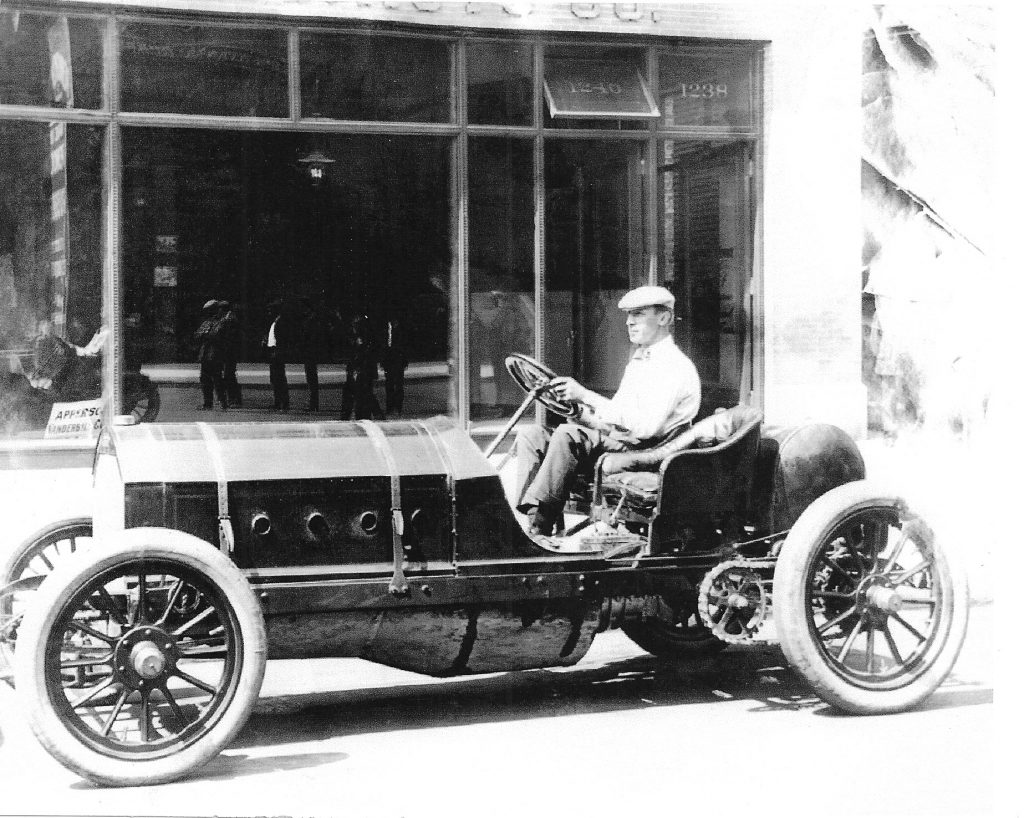

Before the option of same-sex marriage existed, some men in same-sex partnerships found that adult adoption proved a useful way to provide legal and financial cover for their partners. Elon Green, for example, reveals how some men adopted their partners during the 1970s and 1980s, a time which saw increasing homophobia amidst the AIDS epidemic. He describes the culture of secrecy surrounding the practice, noting that some men risked being charged for incest. In a more well known example, the pianist Liberace promised to adopt his younger male lover in the 1970s as a way to protect and care for him. The strategy of adopting an adult lover was not just a product of the later twentieth century. Evidence suggests that wealthy businessman Edgar Apperson, one of the first American automobile innovators, considered himself to have fostered and adopted two young men with whom he had formed long-term relationships.

Edgar Apperson’s first marriage ended in a contentious divorce. His wife had lived for extended periods in Colorado for her health, but he threatened divorce should she return home to Indiana. When she did, after years of “indifference amounting to abandonment,” as reported in the Kokomo Tribune on 5th August 1910, their 18-year marriage ended; there were no children. Apperson was, in fact, twice married, a fact which probably explains why his queer life, and possible homosexual relationships, has been overlooked. Scholars have, of course, accumulated ample evidence for instances of married men who enjoyed extramarital relationships with other men.

In June 1911, after Apperson’s divorce was finalized, a news article in Wisconsin newspaper The New North, reported that a male employee of his had sustained injuries in a dramatic boating accident. The injured, Ralph Polly, 25, was later described across different newspapers’ reports variously as: a caretaker for the Apperson home and farm in Rhinelander, Wisconsin; a “hunting and fishing guide”; a driver for Apperson on land and water; and as Apperson’s pilot. Certainly, they could have been just employer and employee, but Apperson himself suggested a close, intimate 17-year relationship, and he shared that sentiment with the public in his newspaper interviews.

When Polly was killed in a car accident in 1928, the Kokomo Daily Tribune revealed that he had long lived with and visited Apperson in Arizona and Indiana, and “was personally known to many of Mr. Apperson’s friends and to many of the employees of the Apperson factory.” In an article in the Rhinelander News, written the day of Polly’s funeral, Apperson sought to shift the blame away from Polly’s driving and claimed instead that the deadly accident was a result of a heart attack. The same article described Apperson as the “wealthy automobile manufacturer and foster father of the victim.” (emphasis added) With Polly’s death, Apperson sought to assert publicly their private, familial-level connection. When Apperson was himself “seriously injured” in a car accident in 1934, an article in Twin City News remembered the long-dead Ralph Polly, describing him as Apperson’s adopted son, once again suggesting their intimacy.

Apperson’s description of Polly as a son may have served as a subterfuge for an intergenerational homosexual relationship. Modifying language acknowledged this was not a biological relationship, but one of choice and care. Denied the ability to live openly as a couple, Apperson may have used adult adoption as a societally acceptable way to assert their intimacy, while perhaps simultaneously shielding elements of it. Their relationship lasted at least 17 years.

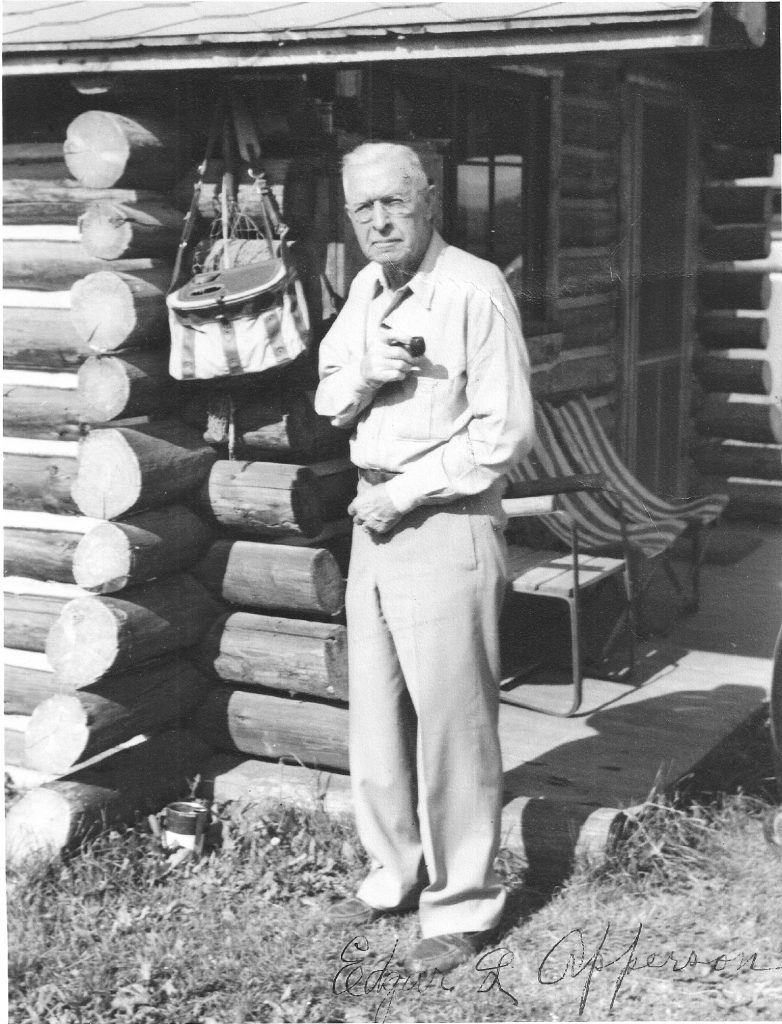

It seems that the language of foster son and adoption proved useful enough that Apperson employed it in another same-sex relationship after he had married his second wife Inez Marshall. Apperson had married Marshall in 1915 and in 1927, at the age of 57, he met 25-year-old Gilbert Alvord. Alvord went on to live with Apperson and his wife for decades. The 1930 census shows Edgar and Inez living with Alvord, who was listed as a servant. In 1940, he was still living with Edgar and Inez, having moved permanently from Indiana and Wisconsin to their ranch in Phoenix, Arizona. The census now described him as a secretary to a retired businessman.

After Inez’s death in 1942, Apperson and Alvord summered each year in Afton, Wyoming. In 1954, the local paper, Star Valley Independent, reported that Mr Apperson, along with his ‘companion and business associate’ had vacationed together in Afton, as they did every year.

Reports of Apperson and his male companions suggests intimate relationships of shared travel, work, and adventure. As Historian John Howard observed of male homosexuality in Mississippi in the mid-twentieth century, rural America abounded with opportunities for homosocial intimacy and sexual encounters. With the trappings of fishing and hunting, men escaped the watchful eyes of their communities and explained away their isolation from family and friends. As historian Rachel Hope Cleves likewise notes, “Small communities can maintain the fiction of ignorance in order to preserve social arrangements that work for the general benefit.” Apperson’s experiences, conditioned as they were by the acceptance of his ‘adopted’ and ‘foster’ sons in Rhinelander, Wisconsin; Phoenix, Arizona; and Afton, Wyoming emboldened him so that he could return to his hometown of Kokomo, Indiana and be photographed in the Kokomo Tribune with his adult ‘foster son’ and ‘close companion’ Gilbert Alvord.

When Edgar died in 1959, he left his entire estate to Alvord. An article in Afton Star Valley Independent commemorating Alvord’s death just two years later categorically referred to him as “a companion” of Apperson, but speculation about their connection persisted. A further article in the Arizona Republic in March 1962 noted, “Childless, the couple befriended Gilbert Alvord when he was in his early 20s.” Indeed, “Friends say they [the Appersons] had an unwritten agreement that if Alvord would remain with them and stay single, that they would leave their estate to him.” However, following Inez’s death, the two men had formalized their financial relationship, declaring themselves in their 1947 Realty Mortgage as “Joint Tenants with Full Rights of Survivorship.”

Apperson’s life may thus provide us with an early example of how men in intergenerational partnerships could, in some measure, publicly share their lives together through the ambiguity of familial roles and the use of adult fostering and adoption.

Katherine Parkin is Professor of History at Monmouth University. She is the author of the newly released Women at the Wheel: A Century of Buying, Driving, and Fixing Cars (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). Her first book, Food is Love: Food Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America won the Emily Toth Award for Best Book in Feminist Popular Culture.

Katherine Parkin is Professor of History at Monmouth University. She is the author of the newly released Women at the Wheel: A Century of Buying, Driving, and Fixing Cars (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). Her first book, Food is Love: Food Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America won the Emily Toth Award for Best Book in Feminist Popular Culture.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Well written Katherine.

Thank you, Plaserae!

Very interesting, thank you.

Thanks so much! Nicholas Syrett is also working on a couple with some interesting parallels. You might want to check it out, too! https://www.colorado.edu/gendersarchive1998-2013/

Very interesting article indeed. It demonstrates that intergenerational relationships, while seemingly frowned at by society, are historically not uncommon at all. There is hope!

Thanks, Mark! Intergenerational relationships certainly existed, but these various methods of hiding them seemed to be part of what makes them hard to see, then and now. In both my study and Nicholas Syrett’s, wealth (and fame) helped ease people’s acceptance/tolerance, or at least bought the men space to live as they wanted (far away from others).