Now that everyone is talking about fascism, let’s mull this over: the struggle against fascism gave the world its first openly gay politician. As I describe in Sex and the Weimar Republic, as the Nazi Party vied for power in Germany in 1932, an antifascist outed a top Nazi, Ernst Röhm, by publishing a series of letters Röhm had written about his own sexuality. The macho Röhm, a key early backer of Hitler, was then head of the Nazi Party militia, the Stormtroopers. In the letters, he described his desire for men, writing “I consider myself to be same-sex orientated [gleichgeschlechtlich].” The outcome of a subsequent libel suit forced Röhm to tacitly concede in public what he never denied in private – that the letters were not fakes and he was, indeed, same-sex orientated.

These days, the Right is in power in the United States, and people are remembering the first openly gay politician, that is, Ernst Röhm. 2017 brought a wave of new essays on what Röhm means for those of us living in the age of Trump. Commentators generally re-told Röhm’s story for one of two reasons: either as a way to note that – surprise! – there are queers on the far right or to recycle the very old, erroneous claim that fascism was queer. (I and others have critiqued that claim.)

Is there an Ernst Röhm for our moment? Yes, I’d submit, but the conclusions people are drawing are plagued by two problems. Both are problems that arise from the way we historians go about writing gay history.

#1. Queer Fascism

Almost one hundred years after antifascists outed Röhm, why are people still so shocked to find queers on the far right? The shock comes from the flawed assumption that queers by definition are liberal or left-of-center.

So, for example, when Trump nominated an arch conservative judge to the U.S.’s highest court, one widely circulated commentary suggested that despite his an anti-trans record, the judge, Neil Gorsuch, must be a moderate on gay rights because he had a close gay friend. (As it turns out, Gorsuch is not a moderate on gay rights.)

Yet some “gay friends” are right-wing extremists. They do not necessarily share the political goals of left-leaning queers. They see their broader, right-wing politics as compatible with their queerness. A queer far-right, anti-liberal, racist movement dates back to the nineteenth century. It is as old as other branches of what Germans called the “homosexual emancipation movement.”

Röhm was not a queer man who suddenly joined a homophobic political party in a fit of inexplicable, profound confusion. His views on sexual politics were, rather, comfortably within what in his day was a decades-old tradition of far-right queerness. Röhm’s queer fascism was identical to the Nazi Party’s ideology in almost all respects, save on questions of male-male eroticism. That was, however, a significant difference. Queer fascism was not synonymous with what one might call “mainstream” fascism – that is, fascism as articulated by big Nazi institutions, such as the Party. The Nazi Party’s position on homosexuality was that it was a dangerous, emasculating threat and ought to be eradicated. Jews supposedly promoted it in order to undermine the “Aryan” race. (Nazi thinkers had a number of other fears about homosexuality, too. See Geoffrey Giles on this.)

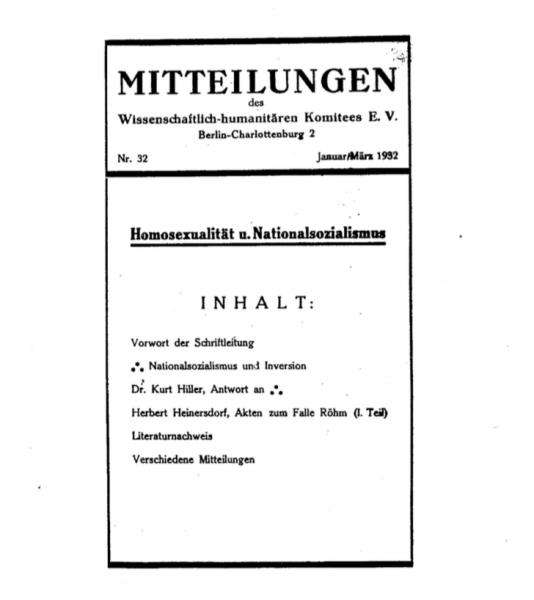

A long-forgotten essay called “National Socialism and Inversion” allows a close look at queer fascism. The essay is part of a public exchange that a man in Röhm’s circle had with the most famous of Germany’s homosexual emancipation groups, the center-left Scientific Humanitarian Committee (SHC). The author of “National Socialism and Inversion” was a member of the Stormtroopers; he is identified in the text only as “Anonymous.”

Anonymous did not exactly disagree with the mainstream Nazi Party’s position on male-male eroticism. He, too, hated homosexuality. To Anonymous, “homosexuality” meant male femininity, Marxism, and Judaism. Yet in his worldview, there were multiple queer subjectivities, or multiple ways to be a queer person. What he saw in himself was not “homosexuality” but something else entirely, a “manly Eros” that was spiritual rather than lustful, and was experienced discreetly among “healthy and respectable fellows” in the Nazi Party militia.

“Manly Eros” was, Anonymous wrote, “fundamentally” different from homosexuality as defined by the left-leaning SHC, a form of male-male eroticism he associated with feminine men, gender-crossing, and transvestitism. He hated the limited public queer culture that existed in Germany in the 1920s, the dance palaces, the magazines, and the moonlight cruises. The SHC’s advocacy of citizenship for homosexuals was steeped in “liberalism and Marxism,” he wrote, and “violate[s] the characteristics of our race.” But masculine, discreet, manly Eros was wholly compatible with a healthy “Aryan” racial consciousness.

Just to be clear: the male-male eroticism about which Anonymous waxed poetic was not incidental to his fascism. It was, rather, the foundation of it. (On this see also Andrew Wackerfuss’s recent book.) Anonymous wrote that the hand of a Nazi militia man “can strike a blow but also caress.” The blows being struck by those hands were against Jews, Social Democrats, Communists, and homosexuals. From the barracks where discreet, manly caresses took place under cover of night, in the morning militia men marched forth to beat anti-fascists to death.

What Anonymous wanted from other fascists was quiet accommodation, not public acceptance. He argued that most Nazis would overlook homoeroticism in the barracks as long as the men in question did their “duty.” Even as he celebrated queer fascism, he took pains to accommodate the anti-queer sentiments of most fascists.

As I have argued elsewhere, this is not “homonormativity”; to paraphrase Lisa Duggan – it did not seek a demobilized queer subject with a private sex live. Rather, it mobilized a certain kind of far right subject with a certain kind of sexual-political ideology. That ideology affirmed homoeroticism, albeit hidden homoeroticism, rejected “homosexuality,” and embraced violence and racism.

Anonymous’s vision of homoerotic fascism does not seem to have thrived within the Nazi Party. Though not all historians agree about this, my reading of the documentary evidence is that the Nazi State – which murdered more men for the “crime” of having sex with men than any other state – never got on board with Anonymous’s politics.

At the same time, far-right queer politics outlasted 1933. One of the leaders of Germany’s current far-right party, the Alternative for Germany, is an out lesbian who has two children with her partner. In Trump’s victory in the U.S. there were inklings of a queer right, one that is not so different from Anonymous’s vision. It sees same-sex eroticism as a valued part of a racist, far-right politics.

#2. Queer Liberalism and the End of Gay History

There is no natural political position for people who feel same-sex desires. There is, however, a political tradition that has most often been the home of queer activism in the twentieth century. It is liberalism. Represented in the U.S. by groups like the ACLU and the Human Rights Coalition, queer liberalism applied classical liberal theory to sexuality. It rallied against sodomy laws and for gay marriage.

Sometimes it seems like queer liberalism was the only gay politics that ever existed. Recent histories foreground liberal gay politics to the point where its successes appeared like a sort of queer “end of history.”

In Leigh Anne Wheeler’s How Sex Became a Civil Liberty and Lillian Faderman’s The Gay Revolution, both books on the sexual politics of the U.S. published shortly before Trump’s rise, liberal activism gradually achieves most of its goals. By the end of these books, queer history seems to have come to an end point. It is a happy endpoint, if one likes queer liberalism. Faderman wrote in the June 2015 epilogue to her book: “Despite occasional setbacks, it’s undeniable: the arc of the moral universe has been bending toward justice. Frank Kameny’s observation bears repeating: ‘We started with nothing, and look what we have wrought!’”

If one takes queer liberalism to be the only gay politics possible, not only does Röhm seem like an aberration, his political project seems like a thing of the past.

But it is not a thing of the past. The history of sexuality also shows that the passage of time can bring a dramatic reversal of liberal gains. The Weimar Republic, Germany’s first parliamentary democracy (1919-33), did far more to advance a liberal gay rights agenda than any other state had up to that point. It also did a lot for people who self-identified as “transvestites,” an identity category that was a forerunner of transgender. When they came to power in 1933, the Nazis promptly wrecked many of those gains.

After 1945, it took many decades for any other state to embrace a middle-of-the road, liberal gay political agenda to the extent that the Weimar Republic had. For example, the Republic nearly repealed its sodomy law in 1929. But harsh sodomy laws remained on the books in West Germany into the 1960s; the United States only scrapped its sodomy laws in 2003. It likewise took many decades for trans people to win the legal ability to change one’s legal first name to a gender-neutral name, something they could do in Germany prior to the First World War. New York City was still debating whether to allow such name changes in the early 2000s.

What existing histories of queer politics have left us unequipped to see – and would that there was no need to see this – is that liberal gains are fragile. Russia’s crackdown on the queer public sphere and the torture and murder of gay men by Chechen authorities are responses to queer politics in the twentieth century, and are very much of our own time, not throwbacks to the past that will vanish of their own accord. So was the (happily failed) American candidate for senate who wants to re-criminalize sodomy.

In addition, history shows that there are various flavors of queer politics. There are far-right queers who don’t support the goals of queer liberalism.

Röhm’s story is more relevant now than we thought.

Laurie Marhoefer is a historian at the University of Washington who writes on queer and trans history and the history of racism in twentieth-century Europe. Her book Sex and the Weimar Republic: German Homosexual Emancipation and the Rise of the Nazis chronicles the fate of the world’s first queer and trans political movements in jazz-age Germany, during the run-up to the Nazi seizure of power. She also occasionally writes in the mainstream press on contemporary American politics, fascism, and queer activism.

Laurie Marhoefer is a historian at the University of Washington who writes on queer and trans history and the history of racism in twentieth-century Europe. Her book Sex and the Weimar Republic: German Homosexual Emancipation and the Rise of the Nazis chronicles the fate of the world’s first queer and trans political movements in jazz-age Germany, during the run-up to the Nazi seizure of power. She also occasionally writes in the mainstream press on contemporary American politics, fascism, and queer activism.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I would argue that the fascist homoeroticism you describe is not queer at all, but rather an attempt to split certain types of homoeroticism away from queerness. To me queerness means embracing gender fluidity, trans identities, etc. as viable and valuable, to subvert the entire structure of patriarchal masculinity. Röhm wasn’t queer, and neither were ancient Greek and Roman pederasts, who saw their sexual use of male non-men (keep in mind that “man” in the sense of the Latin word “vir” was a very restricted category in the ancient Mediterranean world that excluded many, sometimes most adult cis males, and of course all boys) as perfectly in line with being a husband, father, and head of a patriarchal household.

I must take issue with two fundametal points in your thesis. Firstly, you appear to have intertwined two ideological concepts – Fascism and Nazism – and amalgamated them into one. However, the two theories were substantially quite different. Both were ultra-nationalist, but strictly speaking the origins of fascism as defined by Gentile and Mussolini lacked the racial nationalism that was to become so prevalent in Nazi Germany.

Secondly, you talk about ‘queer fascism’, but here I struggle because while I acknowledge an ageless history of gay oppression, I struggle with the use of the word fascism. We live in a world where intolerance is on the increase and throughout Europe people are waking up to the realisation that antisemitism, racism and oppression of Gay communities are on the increase. But what happens when we encounter genuine ‘fascist’ movements if we ‘water down’ the term to use it as a broad label to explain hatred and persecution. Sadly, fascism is more insidious and evil than that and we need consequently to be more cautious in our language.

It is a topic I hope to follow more fully in my own blog at tacitus-speaks.blogspot.com