Saniya Lee Ghanoui

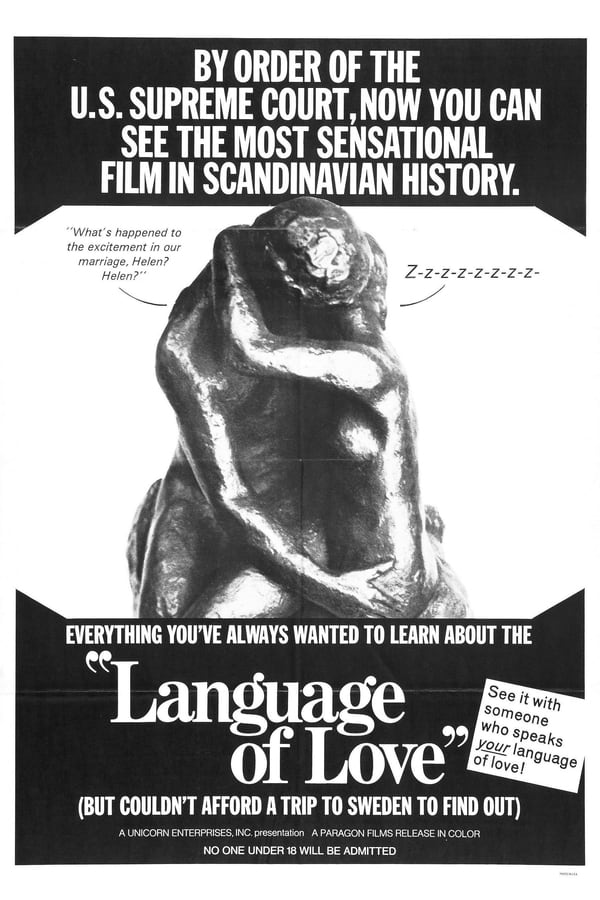

In the autumn of 1969, U.S. Customs seized the recently imported Swedish film Language of Love (Ur kärlekens språk). On October 31, the New York Times put forward its own definition of the film and called it “a new, Swedish-made sex education film.” The Times interviewed an attorney for Unicorn Enterprises, the U.S. distributor of the film, who also disputed the government’s claims of obscenity, and maintained that the film was “neither obscene nor immoral and is of social and educational value.” Nonetheless, a legal battle ensued before the court authorized the film to enter the U.S. in 1971.

Language of Love focuses on sexual problems, pleasure, and couples’ desires to achieve a better sex life. A group of expert witnesses narrate the film and serve as authority voices. Sten Hegeler, a sex psychologist, and Inge Hegeler, a sex counselor, were themselves a married couple whose popular sex column, Inge and Sten, and a well-read sex dictionary, called An ABZ of Love (1961, English translation 1962), made them respected Swedish national authorities on all matters sexual. Sexologist Maj-Briht Bergström-Walan and gynecologist Sture Cullhed also join the Hegelers. These experts address sexuality openly, with Bergström-Walan decrying the current social problem of sexuality as “a wave of taboo” and Inge noting that it is “a whole complex of taboos.”

The film begins with a number of staged scenes where different couples act out sexual problems: “difficulty in communicating,” “intolerance,” “male vanity,” and “disparaging the man’s virility.” The experts all agree that there is no perfect sex life, but that their goal is to create “a film about being together.” After these opening vignettes the film turns to female satisfaction, a concept seemingly foreign to both sex education and pornographic films of the time. Inge asks the group about female sexual pleasure and why society does not focus on it as much as men’s; she states matter-of-factly that it is important for females to be sexually satisfied. The experts comment that they want to add female perspectives to sex education to counter the male-dominated instruction, and Language of Love achieves this by showing scenes of unsimulated sex, including a woman masturbating.

The film frequently mentions the Masters and Johnson four-stage human sexual response cycle. In one scene, a heterosexual couple copulates while a split screen shows a graph that documents the man’s progression as he goes through the four stages. By including Masters and Johnson’s study, the filmmakers position Language of Love as an authoritative voice grounded in scientific research. The Hegelers often refer to the Masters and Johnson study as they emphasize the joys and pleasures of sexuality while treating it as a serious topic of discussion.

Language of Love also mirrors the sex experiments that Masters and Johnson conducted. Throughout the film, audiences see a film set where couples have sex. Instead of using illusions or simulated sex acts, Language of Love depicts authentic sexual intercourse with a pedagogical intent. The sex scenes sought to communicate sex’s “natural” state as opposed to the constructed portrayals in pornographic films. Even though the set—a platform in the middle of a room that slowly spins in circles—is anything but natural, it allows the audience to see sex in tandem with the experts’ narration.

While the majority of the film shows heterosexual sex acts, one scene explores homosexual sex. The scene begins with the group of experts explaining the normality of having fantasies during sex, including same-sex acts. Inge explains that it is perfectly acceptable to fantasize about sex with someone of the same gender, and the audience sees a heterosexual couple having sex. As she talks, the woman dissolves into a man, and the two men kiss. The scene returns to the heterosexual couple having sex, except this time the man dissolves into a woman. Editing gimmicks and Inge’s narration make homosexual fantasies an accepted reality.

Due to the number of sex scenes, U.S. officials contended that the film was obscene, and the rhetoric from the court case shows how the court grappled with defining the nature of the film. In the ruling of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, Judge Moore wrote that Language of Love was “a movie version of the ‘marriage manual’—that ubiquitous panacea (in the view of some) for all that ails modern man-woman relations.” In this sense, the Court found that the film functioned as a self-help guide and not as pornography. The decision the court faced centered on “the manner in which sex is presented, not its frequency, variety or explicitness.” Here, the court concluded that the amount of sex meant little in comparison to its exhibition, thus showing that the presence of sex did not automatically relegate a film to the pornographic or obscene.

When the film finally premiered in the U.S. in 1971, film critics tended to identify the film as educational rather than pornographic. In a July 1, 1971 article from the New York Times one reviewer called the film a “Swedish-made color documentation of sex” that “leave[s] the impression of trying to inform without leering.” The critic noted that theaters were showing the English-language version as opposed to the original Swedish-language version, but that “educationally, it’s the same the world over.” Language of Love actively sought to destroy the taboos and misconceptions about sexuality. As in the U.S., Sweden went through a period of political, social, and sexual change during the 1960s, and, as film scholar Elisabet Björklund argues, this greatly impacted the ways filmmakers produced new sex education films. Whether Language of Love is pornographic or educational may still be up for debate, but the film was at the forefront of this conversation.

Saniya Lee Ghanoui is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an Editor for NOTCHES. Her research examines the histories of sexuality, media, and medicine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries United States and Scandinavia. She tweets from @Saniya1.

Saniya Lee Ghanoui is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an Editor for NOTCHES. Her research examines the histories of sexuality, media, and medicine in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries United States and Scandinavia. She tweets from @Saniya1.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com