In the 1950s and 1960s, the Supreme Court began relaxing pornography and censorship laws, while at the same time, cheap printing materials became increasingly available. This caused an explosion in pulp fiction, with publishers issuing salacious new books on a weekly basis. Exact numbers are currently impossible to determine, but pulp circulation was high, oversight was low, and titillating fringe themes sold well. Queer pulp authors used that state of affairs to their advantage, and the relative lack of editing for their work means their opinions arrived on the page nearly unfiltered.

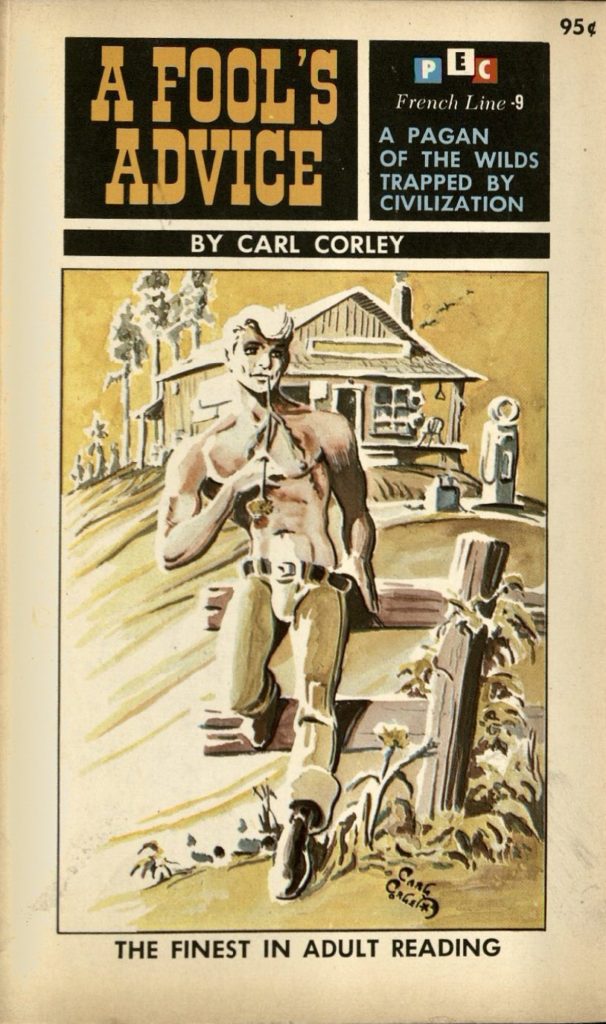

Carl Corley, an author and artist from Mississippi and Louisiana, is one example. Corley published 21 novels under his own name, mostly in the late 1960s, immediately before Stonewall. He illustrated most of their covers himself, and chose to use his own name as a literary rebellion, a statement of pride in his work and subjects. He was known for his country-boy protagonists, rural themes, and romantic turn of mind, and seems to have been an outlier representing not only gay pulp, but gay Southern pulp.

Corley used his platform to write semi-autobiographical novels exploring different aspects of his Southern background, and some of his most interesting content comes in his character descriptions and plots. He spent uncounted pages exploring ideas about queerness and preoccupation with terminology. Corley rarely used the words “homosexual” or “gay,” finding them too medical and too feminine-sounding respectively, although he was aware of both. “Queer” seemed to be a word serviceable in a variety of contexts, one he could expect to be understood, but it was not initially enough.

Many of his younger protagonists have absolutely no prior knowledge about queerness, and only discover the idea when they hear a derogatory term, usually “fairy.” These boys frequently narrate their first sexual experiences as teens and usually consider it quite natural, just happening to fall into sex after admiring another boy. Later, they discover the existence of queer subcultures from other men or by visiting a gay bar. More mature characters have often heard of queerness at school or during military service, but they typically do not identify with it because they associate words like “queer” and “fairy” with cross-dressing and effeminate behaviour.

Corley, too, probably grew up with “queer” as a gender-related slur, and his concept of queerness remained closely linked to gender expression. His protagonists are inevitably physically small, prefer to be the sexually penetrated partner, and even express desires to be “wives” for their partners and keep house for them. For most protagonists, receptive anal sex seems to be the most natural thing in the world, despite acute pain. (There is no mention of lubrication until Corley had already issued several books, making one wonder if he heard about the possibility from readers.)

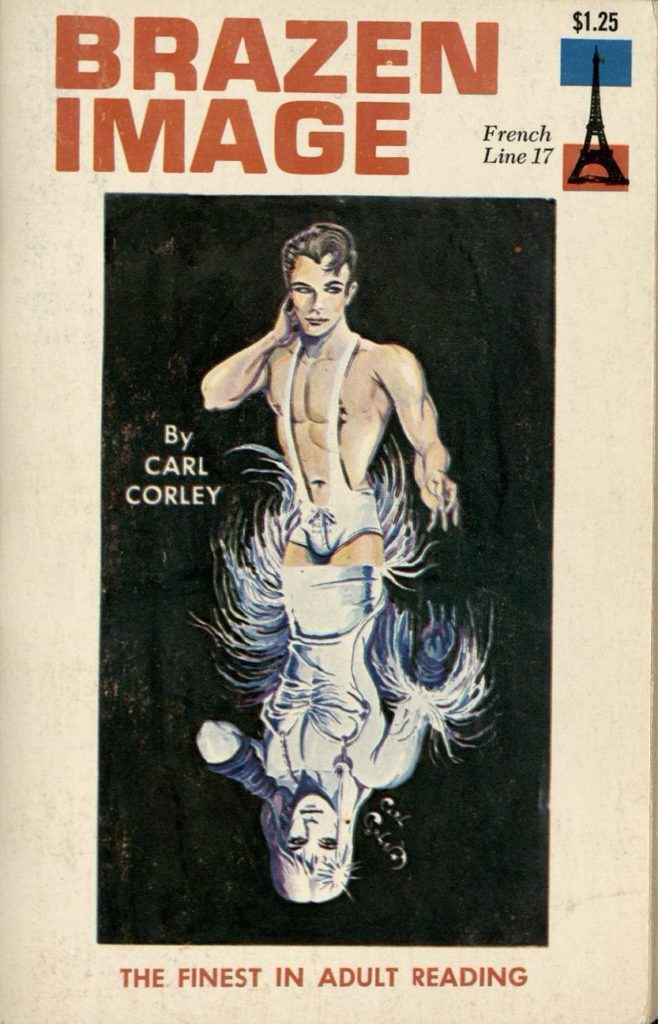

During his extensive descriptions, however, Corley constantly reassures readers that his protagonists are “all male” and “utterly masculine.” Their clothing, stance, and actions are entirely masculine, rejecting any sense of effeminacy in dress or of behaving in a girlish way. Yet he also wrote frequently about the practice of female impersonation, and his 1967 novel Brazen Image stars a young female impersonator named Dewy Bow. The young performer feels more conflicted about his queerness than other characters because of his family’s judgment, adding another dimension to Corley’s defensiveness about female-coded behavior. Corley draws a stark line between Dewy’s authentic femininity and that of the other drag performers who allegedly want to be women, perhaps indicating that he thought of Dewy as a trans woman but didn’t know any useful terminology for trans or nonbinary experiences.

In 1966, Corley published A Chosen World, his first and most autobiographical novel, in which he suggested his own naming system of “toros” and “mannequins.” “Mannequin” replaced “the gays, the faggots, the queens, the nellies—those of exaggerated femininity,” because they were “alive, yet not alive, more doll like than human, more life like than statues—yet glittering with that artificial glow which holds in its realm a fascination unequalled.” “Toro” replaced the term “masculine homosexual,” chosen because it was “the most masculine word in the human language today.” He continued, “I shall refer to these as Toro’s [sic], so that from my mind to the world, I hope, this therm [sic] will eventually stick and find its place among those unappropriate [sic] terms which will fade out completely and become forgotten.” Ironically, his invented naming convention has been completely eclipsed by others, and he stopped using them himself in later books.

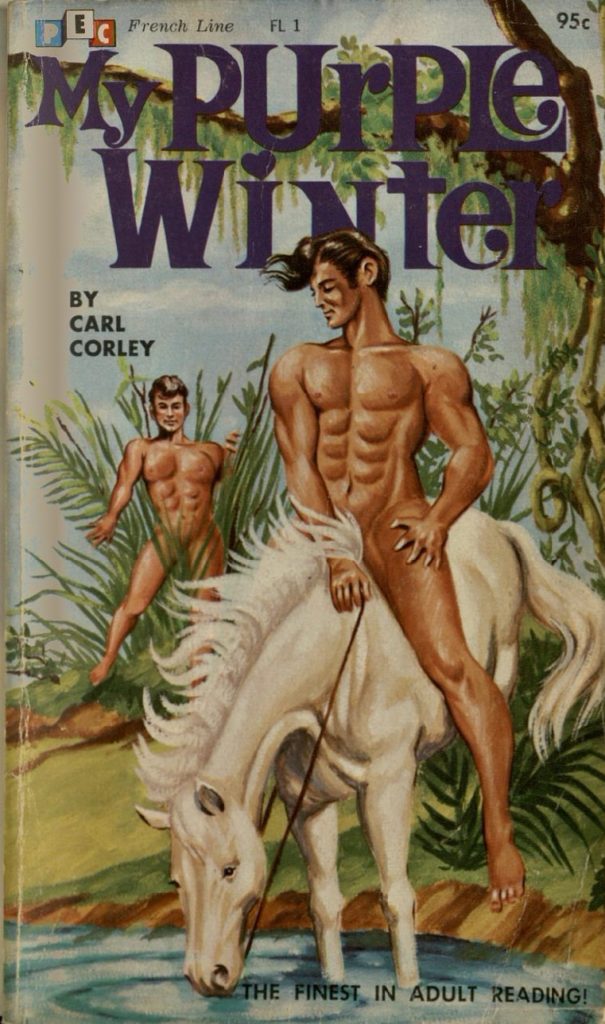

Still, even in the same year, Corley wrote in My Purple Winter: “A fairy is a man, like us, who loves only other men. Some are masculine in their personalities, others are more feminine.” Characters do not consistently embrace “fairy” as an identity word, but his explanation captures the idea that something connects gay men across gender expression, and gender presentation may not be as important as he originally thought.

No matter what the word, Corley was identifying subsets of queer men, whom he understood to be a separate type of man based on sexual and romantic attraction to other men. For Corley, queer men might be masculine or feminine, even potentially nonbinary, but were still part of one class. Straight men might engage in sex with a queer man but were not part of the classification, and although he did not seem to know the word “bisexual,” he seemed to harbour no ill will toward bisexual men and included them in his definition.

It is unclear if Corley’s idiosyncrasies were specific to him or if they were common attitudes at the time among rural Southerners. His opinions are often contradictory and unexamined, especially where gender is concerned, and his whole body of work is an attempt to examine them, but by the end of his life Corley had embraced the word “queer” to describe himself. In a short unpublished memoir, he wrote that he appreciated its connotations of oddness. Although he did not specify, perhaps “queer” also served to include gender nonconformance. In either case, his work contributed to a national dialogue about gay identity, open sexuality, and demand for respect. Even while he wrestled with classifications, he created a rare visibility for rural queer people within that debate, and his struggles with terminology and gender illuminate one stage in a dialogue that still continues.

All of Carl Corley’s novels, along with art and unpublished comics, can be read and viewed at www.carlcorley.com.

Hannah Givens is an independent historian in Georgia, focusing on queer Southern literary history. She received an MA in History with a concentration in Public History from the University of West Georgia in 2018.

Hannah Givens is an independent historian in Georgia, focusing on queer Southern literary history. She received an MA in History with a concentration in Public History from the University of West Georgia in 2018.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Brava! Your work is fabulous!