Ishita Pande

Sex, Law and the Politics of Age: Child Marriage in India, 1891-1937 is a microhistory of a law restraining child marriages passed in colonial India in 1929, and a critical account of the emergence of “age” as scientific and governmental object, crucial for upholding the rule of law, for governing intimate life, and for securing gender rights and social justice, in twentieth century India.

NOTCHES: In a few sentences, what is your book about? Why will people want to read your book?

Pande: My book recounts the history of a law regulating child marriages in India that was passed in 1929. Through a close reading of that law in its historical context, I show how the legal norms and moral codes regarding age in the governance of sexuality that are taken for granted around the world were created at the nexus of colonial history, bureaucratic procedures, and a narrowly juridical understanding of the human. My book relocates the history of child marriage in India into a wider terrain by asking “global” questions, such as: What makes a child legible to us as a child? At what ages has childhood been considered to end at various times in history, and why? Is age a suitable criteria for measuring consent, capacity, and responsibility? In other words, it uses the archives of child marriage in India to show how the logic of law, which presumes that age is a natural measure of capacity, makes possible – and also limits – our understandings of gender justice and human rights.

People will read this work for a quirky history of child marriage that leaves conventional framings of the issue behind, and for its querying of “age” as foundational to modern identity and morality. They will want to read this book, in other words, for what it tells us about the gendered human, about sexual mores, and about how the law circumscribes not only our universe of morality but also our scholarly categories of analysis.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic? What are the questions you still have?

Pande: I was drawn in by the tone of judgment that underlines historical scholarship on child marriages, and set myself the challenge of stepping beyond condemnation, to explore the problematization of child marriage, that is, to seek out not only its emergence as a moral and political concern, but also to understand the form the concern took at different periods of time. I was perplexed by how the contours of the historical writing on child marriage are almost entirely bound up with the idiom and logic of the very law that abolishes child marriages. Historians have written how the ages of marriage settled upon at various points of time were set “too low” in consideration of religious reservations, or they have talked about how and why the law “failed” in its central purpose. I tried to reimagine the history of child marriage by unpicking the language of the law from the terms of analysis, to write a history of a phenomenon that is not yet past.

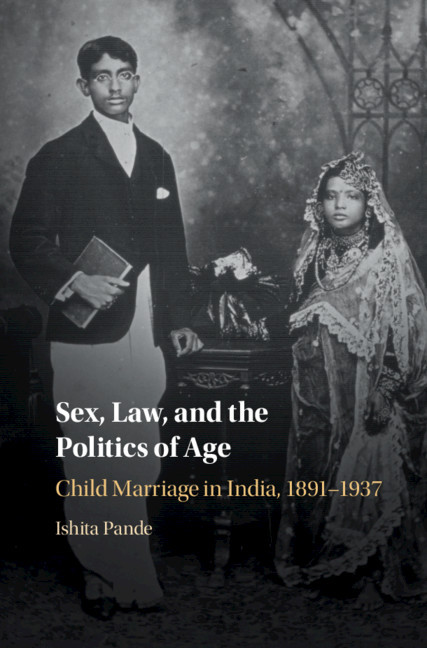

Second, as with most historians, the archives enticed me. As I was finishing up my previous book, I came across ignored sources such as the highly-specific Old Men’s Marriage with Young Girls Restraint Bill (1930), which clarified that for its purposes, “Old Man means a male of 45 years and over, and Young Girl means a girl below 18 years of age.” I found an entire novella in Hindi on the plight of a young boy forced into a child marriage who died of the sexual demands placed on him. My book is not concerned with retrieving weird-seeming and long-missing details from the archives of child marriage, but to ask when and why child marriage came to be understood as a problem in the way we understand it today, so that these other concerns were not only rendered bizarre, but became invisible to us. Third, there was an element of personal curiosity: The photograph I use on the cover of my book reminded me of others encountered in personal albums in my extended family. My maternal grandparents married in 1905, but the minimum ages prescribed by the law that came into effect in 1929 would have rendered the marriage illegal. How and why did my grandmother become a child wife? The pictures, once evidence of the strangeness of my family’s past, became a way to become estranged from the present way of seeing things.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book?

Pande: I started with a systematic reading of legislative debates over bills floated to tackle the problem of child marriage in India between 1891 (when a change to the age of consent sought to discourage marriages under the age of twelve for Hindu women) and 1929 (when the Child Marriage Restraint Bill that restricted the marriage of females below fourteen and males below eighteen passed into law). This legal archive is the bedrock, but I quickly began to see how child marriage was everywhere in the cultural and literary field of colonial north India. Tracts on sexology and eugenics – such as NS Phadke’s Sex Problem in India – were promoted as promising answers to that pressing question of the day: “Do you know at what age you should marry?” Rangila Rasul (The Colorful Prophet) – a notorious pamphlet controversial for stirring up hatred against Muslims in colonial India – appeared to be entirely pervaded by the contemporaneous debates on child marriage. The seemingly dull, dry tables on the age at marriage in the census, it became apparent, caused as much sensation as these provocative texts. I pored over census reports to figure out why the law became riddled with age-defined boundaries between child and adult, even as census officials were insistent that in India, “age is not a matter of fact as in England, but a very doubtful matter of opinion.” As I started asking how, then, was a child recognized as such in the courtroom, I moved on to forensic textbooks to understand how age was “proved.” This, in turn, led me to notice how child wives often appeared in courtrooms in unexpected ways- not necessarily, or even predominantly, as “victims” of child marriage, but as the accused in cases of bigamy. From here, I moved on to texts of “Muslim law” administered in colonial courts – the secular sharia – to understand how questions about age, childhood and sexuality were handled differently in distinct juridical perspectives.

So, my research proceeded without a fixed plan, and the archives expanded – from official records to Hindi pornography, from forensic texts to actuarial reports, from imperial propaganda to communal pamphlets. This is the way things proceed for most us, don’t they?

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time your conceptualized it?

Pande: Yes and no. While the book was about the regulation of child marriages in India from the start, it was always to be a history of childhood and law – or juridical childhood. It was revised in its scope as it became clearer how the story of juridical childhood was integral to understanding the history of colonial governance, national self-definition, feminist politics, and communal propaganda or the vilification of Muslims (in India), and the history of the liberal legal subject and the modern self (globally). It went from being a book about Indian child marriage and the instability of age in India to one about the history of using age to measure legal capacity and even “consent” elsewhere. It ended up arguing that “age” is a legal artifice shored up as a natural value by particular actuarial, forensic and classificatory technologies.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

Pande: I have a rather narrow and simple answer to this question: When I read Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality as a graduate student in India more than twenty years ago (along with The Order of Things and Discipline and Punish) – during what I perhaps mistakenly recall as being “extra” sessions on Foucault taught by the inimitable Majid Siddiqi at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi – I came to understand sexuality as foundational to our structures of thought and to the organization of power. And while my understanding of sexuality has (hopefully) developed in intervening years that took me from Delhi to Kingston, Ontario, via stops in the US and the UK, the sense that sex is fundamental to the very structures of modern power and knowledge has stayed with me. An answer to this question on my engagement with the history of sexuality used to be more visible in the longer footnotes to earlier versions of my chapters, which bore witness to my attempts to reroute Foucault via colonialism (by thinking with Ann Stoler’s work), or querying queer theory from South Asia, or revisiting the question of queer temporalities via the seemingly staid route of “area studies” (in response to the provocations of Anjali Arondekar).

NOTCHES: This book is about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Pande: As an argument about how sex and sexuality pervade our understanding of legal capacity, communal and national identity, and “modern western” notions of homogeneous, empty time, the book speaks to several other themes. As a biography of a single law (The Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929), it showcases a novel approach to legal history; through its deep dive into the distinct forms this piece of legislation took over time, the versions or alternatives to the act that fell by the wayside, the application of the law in courtrooms, the negotiations between various jurisdictions to ensure its application, the book makes a novel contribution to the thriving field of South Asian legal history. While laws governing family have been the subject of several recent books, as a microhistory of a law, as it were, it is able to effectively contribute to a diversity of themes – from the processes by which the domain of “religious” law was constructed in India, to the impact of colonialism on women’s right in India. It details how “chronological age” came to be instituted as a core ingredient of secular personhood through the colonial legal institutions in India, and is a call to integrate age more centrally into legal historical approaches.

It is also designed to be read as a history of childhood, one that primarily inquires into “childhood” as an object of intellectual history. As such, it makes a significant contribution to the history of childhood and youth in India – another burgeoning field. In theorizing the relationship between ideologies and practices of colonial governance, and the emergence of childhood as a “moral category of politics” in the twentieth century, it is a contribution to the wider field, one that insists on the foundational place of race and colonialism in the making of post/colonial childhoods.

As a historical account of how “modern western” notions of temporality as forward-moving, measurable in concrete and discrete units, are made intimate and disseminated through colonial law and reform, it is a contribution to the vast and thriving scholarship on “colonialism and its forms of knowledge.” As I explain in the introduction to the book, in theorizing age as the intimate manifestation of time, I engage with diverse works that trace the colonial history of universal, standard time, or that sketch out the colonial genealogy of the juridical human.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Pande: I will start narrow and go broad. There is a recent surge in work thinking about age and the history of sexuality. I have in mind a recent special issue edited by Nick Syrett on “Sex Across the Ages: Restoring Intergenerational Dynamics to Queer History,” as well as work by historians of sexology such as Jana Funke and Kate Fischer. My book will be a particularly useful complement to these works in a course on age and the history of sexuality, or a general sexuality course with, say, a week on age, as it uses the insights of queer theory to critically examine what is considered the most repressive of heterosexist marital arrangements, and because it brings into our field of vision a part of the world that is so often ignored in the historicization of the sex/age system. It is my hope that a recent forum on “Chronological Age as a Category of Historical Analysis” in the American Historical Review will prove to be a catalyst for teaching and research on age; this book can stand as an example of what using “age” as an explicit category of analysis looks like. It will join a handful of works which effectively utilize age as a category of analysis to comprehend the history of Asia, for instance.

I hope the book will find a place in histories of gender/sexuality in general – as an example of the way in which the child was a linchpin for the organization of sex in modernity. It will also, I hope, find a place in the interdisciplinary scholarship on the entwined histories of childhood and sexuality. It can be assigned in courses on “global” histories of marriage, or the global history of sexology – which are conversations parts of the book explicitly engage with. It will join other works, such as Durba Mitra’s pathbreaking Indian Sex Life (featured here earlier this year) to make the history of sexuality more central in syllabi on South Asian history. Finally, I would like my colleagues to incorporate this book in legal history syllabi as an example of feminist legal studies in India, but also with other meditations on age and childhood in the law in other contexts (such as Holly Brewer’s By Birth or Consent).

Finally, beyond these courses on the history of age, gender and sexuality, legal history, colonialism/imperialism and South Asia, it is my hope that colleagues will find it useful to assign my book in courses on the history of childhood, as a book that “crosses” the history of childhood and sexuality while decentering Euro-American contexts (so to accompany and also to serve as a historical counterpoint to James Kincaid, or Kathryn Bond Stockton); that centers colonialism and empire in the conceptualization of childhood; and that brings the insights of feminist, postcolonial and queer theory to bear on the study of childhood and girlhood in a distinctive ways.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Pante: Child marriage in India is not past, but present. A taskforce appointed to look into the question is recommending raising the age of marriage for women further (to 21), once again falling into the trap of thinking “child marriage” – as well as the relationship between age, consent, capacity, fertility and development – in the narrowly circumscribed ways that I deconstruct in my book. My book shows how the nexus of moral codes and legal norms that constitute child marriage as a particular type of problem (of women’s s rights, child sexual abuse, for instance), also constrain or limit solutions. It shows how history contains examples of perhaps imperfect, yet still heterogenous alternatives to understanding and tackling the problem of child marriages that do not rely on liberal legal frames. These alternatives – such as the option of puberty available to Muslim wives that enables them to leave behind marriages contracted for them in childhood, and which I devote a chapter to – have been strangely neglected in the extensive scholarship on child marriages in India. What is the reason behind the neglect of these other cases involving Muslim child wives, these alternative solutions?

In my book, I show how both Hindu as well as secular nationalist social reform efforts on child marriages relied on an erasure of Muslim legal, ethical and political positions. I show how a reformist discourse on child marriages – seen as a problem of Hindu social reform – was crucial to the political and cultural minoritization of Muslims in the 1920s and 30s. As I answer this question today (August 5, 2020), India’s Hindu fundamentalist PM Narendra Modi is launching the construction of a temple on the site of the Babri mosque, demolished 28 years ago. People are celebrating this moment in my hometown, Delhi, and across India. What happened to India’s secular ethos, many of us are left wondering. The third part of my book is an attempt to grapple with ways in which debates over sex and marriage animated the formation of Hindu nationalist identities, and the twisted abjection of Muslims as the nation’s unhygienic others, but more importantly, it is an exploration of the ways in which secular critique has coincided with what I call a methodological Hinduism even in feminist scholarship. In recalling the absence of discussions of “Muslim law” in the legal history of child marriages in India, and the neglect of Islamic categories of thought in India’s history of child marriage, I try to grapple with feminist shortcomings while pondering the seeming “loss” of secularism in an oblique way.

In doing so, I take (colonial) Muslim law as the ground from which to query what I term an epistemic contract on age – an implicit agreement that age is a universal and natural measure of human capacity and hence of legal and political subjectivity – to show the limitations such a contract poses on gender justice.

This history matters not only for those interested in questions of gender justice in India, but also in human rights and social justice elsewhere. In our times, immigration agents in the United States and several European nations continue to use x-rays to determine the age of migrants – usually to adjust chronological ages of males upwards in order to deny their claims as asylum seekers. In a recent case discussed in this excellent podcast by Nadia Reiman, and explored in the epilogue to my book, we encounter the case of a “potential child wife,” whose chronological age was adjusted from 19 to 17 to 15 by zealous border guards in Chicago keen to protect her from being trafficked, who were aided in their zeal by the flexible conclusion drawn from forensic technologies for age determination (such as dentition and x-rays, which are also discussed in my book). The case of a woman made to age in reverse not only provides a striking reminder of the blinding power of the “child” (especially one perceived to be in sexual danger) to provoke humanitarian action but also points to the constitution of this “child” at the nexus of law, sexual morality, the colonial gaze, and bureaucratic and forensic procedures. The case shows how modern states continue to manufacture age while naturalizing it as a fact about the body. It reveals how standards of age remain uncertain in our times and can be manipulated to undermine rights and to propagate patriarchal or neo-imperialist agendas, even as the use of age standards promises to bestow human rights on each and all. It reminds us, finally, of the danger of allowing a flawed juridical truth to define our entire universe of morality and to function as a transparent unit of social scientific analysis.

NOTCHES: The book is done. What next?

Pande: On to the next book, armed with questions that continue to nag. The new book is a long historiographical/theoretical essay and a deep dive into the archives of “sexual science” in late colonial India. Treating the history of sexuality as an integral aspect of intellectual history and the history of science, I hope to interrogate whether the foundational concepts in the “history of sexuality” (and particularly the field-defining work of the French philosopher Michel Foucault) translate well, and might be applicable to, the historical context of South Asia. By focusing on Foucault’s “four figures” of sexuality (the hysterical woman, the conjugal couple, the masturbating child, the perverse adult) I seek to: a) reroute History of Sexuality via colonialism and India; b) reflect on the un/translatability of “sex itself”, as well as of the tools, methods and concepts we use to understand the various objects we term sex; and c) provide a historical narrative that draws out the importance of the “sexual sciences,” broadly defined, to the constitution of Indian modernity in the twentieth century.

Ishita Pande is Associate Professor of History at Queen’s University, Ontario. She is the author of Medicine, Race and Liberalism in British Bengal: Symptoms of Empire (Routledge, 2010) and Sex, Law and the Politics of Age: Child Marriage in India, 1890-1937 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Ishita Pande is Associate Professor of History at Queen’s University, Ontario. She is the author of Medicine, Race and Liberalism in British Bengal: Symptoms of Empire (Routledge, 2010) and Sex, Law and the Politics of Age: Child Marriage in India, 1890-1937 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com