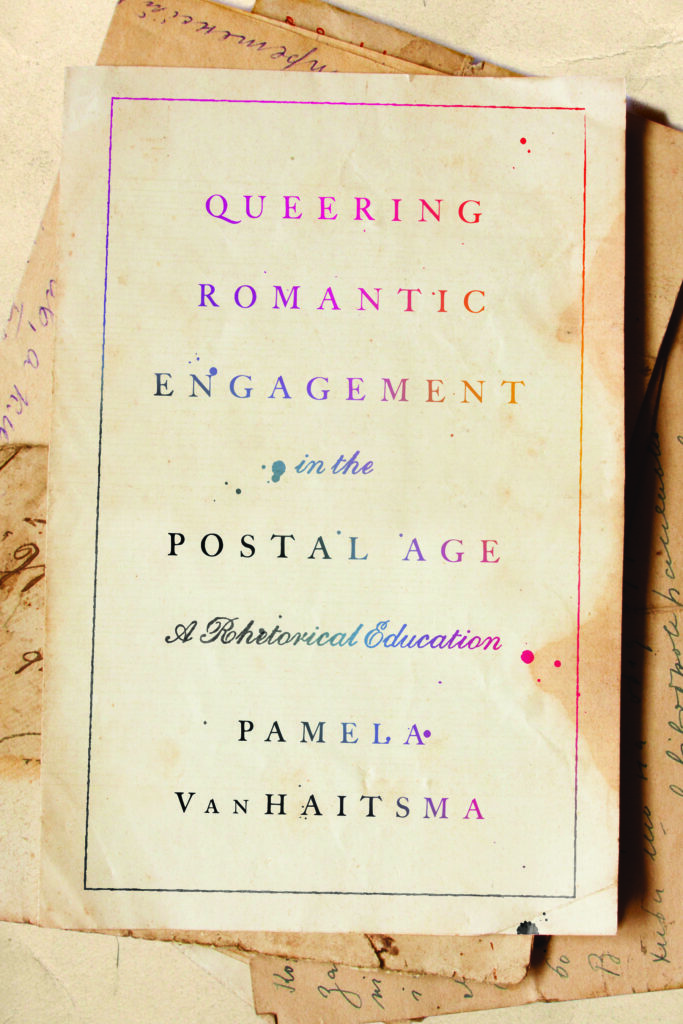

Queering Romantic Engagement in the Postal Age: A Rhetorical Education is a queer history of rhetoric that takes as its touchstone the teaching and learning of romantic letter writing in the nineteenth-century United States. Outside of my home field, transdisciplinary rhetorical studies, the term “rhetoric” is often used to refer only to deceptive (or in this case, seductive) textual maneuvers. I invite readers of my book to think of rhetoric much more capaciously, as practices of symbolic action that we use not only to influence each other, but also to create identifications and compose our relationships. In this sense, the writing of romantic letters is a form of rhetorical practice.

NOTCHES: Why will people want to read your book?

Pamela VanHaitsma: As historians of sexuality well know, romantic letters are central to understanding same-sex romantic relationships from the past. With respect to my book’s period, for example, debates about the nature of so-called romantic friendship turn on conflicting interpretations of letters (and diaries). Too often, however, these letters are treated simply as unstudied expressions of heartfelt feeling and desire. My book offers a rhetorical approach to nuancing our reading of these letters, showing how the genre should be understood instead as a learned and crafted form of epistolary rhetoric. Specifically, I propose a methodology for contextualizing romantic letters in relation to rhetorical education, generic conventions for epistolary rhetoric, and a broader network of related genres.

My queer history of epistolary rhetoric is grounded in archival research at three sites: popular manuals that taught the romantic letter genre (1807–1897), romantic correspondence between freeborn African American women Addie Brown and Rebecca Primus (1859–1868), and genre-queer epistolary rhetoric by Yale student Albert Dodd (1836–1838). These case studies span rhetors who are diverse by gender, sexuality, race, class, and educational background. Yet they all developed creative ways of queering the widely taught cultural norms and generic conventions in order to develop their same-sex romantic and other non-normative relationships.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic?

PVH: I became interested in queer epistolary rhetoric when I was a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh and came upon popular letter-writing manuals while examining archival materials in the Nietz Collection. I was struck immediately by how extensive the instruction in specifically romantic letter writing was. By how his instruction in ways of writing was about composing a romantic self in relation to another. By how obviously such instruction embedded within its lessons on genre conventions normative ideas about gender, sexuality, race, and class. By how heteronormative the instruction was and, at the same time, how marked by slippages that might enable queer practices.

I couldn’t help but imagine how I, as a queer femme, might appropriate the manual pedagogy to pursue my own desires. In doing so, I started to wonder about how people in the nineteenth-century United States used (or not) these manuals, especially when their non-normative relationships were not represented in the models letters offered by the manuals. Thus began the archival research for my book.

NOTCHES: This book is about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

PVH: The book also speaks to the history of rhetoric and rhetorical education. The dominant view of rhetorical education, handed down from Greco-Roman rhetorical theory, is that it prepares students for civic engagement, defined as active participation in political life through public discourse. This view, as Karma Chavéz has argued, is tied to a normative understanding of rhetoric, education, and citizenship. In effect, this normative approach has marginalized questions about the discourse of queer intimate life within rhetorical studies. My history responds by theorizing a concept of rhetorical education in service of what I call “romantic engagement.” I define rhetorical education for romantic engagement as the teaching and learning of language practices for composing romantic relations. I use the term “composing” in a dual sense: people learn arts for composing in order to participate in romantic relationships, and this rhetorical practice composes the relationships themselves. In this sense, instruction and practice are rhetorically constitutive of romantic relations and even subjects. While this concept of rhetorical education emphasizes romantic life, it does so with the recognition that the pedagogical shaping of romantic subjects is a profoundly public process imbricated in civic life.

Ultimately, I argue that such rhetorical training shaped citizens as romantic subjects in predictably heteronormative ways and, simultaneously, opened up possibilities for queer rhetorical practices that subverted genre conventions and transgressed generic boundaries.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book? (What sources did you use and were there any especially exciting discoveries or any particular challenges?)

PVH: Most of my archival research for this book was conducted in the University of Pittsburgh’s Nietz Collection, which holds letter-writing manuals; at the Connecticut Historical Society, where I examined Addie Brown and Rebecca Primus’s correspondence; and in the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives, which holds Albert Dodd’s letters, commonplace book turned diary, and an album of poetry. Working in all of these collections was exciting for me, especially as a graduate student who was conducting archival research for the first time, and I am grateful to the archivists and special collections staff who helped make the work possible.

One challenge confronting my research was that, as in most histories of queer relational and rhetorical practices, the archives were marked by silences, absences, and elisions. In response, I drew on the work of Jacqueline Jones Royster in order to develop a queer version of what she terms “critical imagination.” Elsewhere I have conceptualized critical imagination in relationship to gossip, as a queer rhetorical and historiographic methodology, and now I see these approaches as resonant with Saidiya Hartman’s “critical fabulation.” For my book, such approaches allowed me to speculate about how people may have used and subverted heteronormative instruction even where archival records are limited.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

PVH: I’m currently working on my second book project, tentatively titled The Erotic as Rhetorical Power in the Romantic Friendships of Women Teachers, 1848–1922. Further interrogating the civic dimensions of rhetorical education, this project is a queer feminist history of rhetoric that recovers the civic contributions of women teachers in same-sex romantic friendships. How, I ask, did the erotic of these women’s intimate relationships fuel their public work as writers, orators, and teachers of rhetoric?

To investigate this question, I define romantic friendships as relations in which the erotic, in Audre Lorde’s terms, functioned as a source of rhetorical power—as a sharing of passion between women that was marked by intellectual admiration and stimulation, animating not only their relationships with each other, but also their rhetorical practices and pedagogies. The women in my study taught rhetoric at freedmen’s schools, boarding schools for girls, and women’s colleges, while also writing and speaking publicly on behalf of the abolition of slavery, educational access, and voting rights. I argue that these women’s romantic friendships, far from being simplistic instances social constraint or sexual repression, helped make possible their rhetorical labors.

I’m also having fun with a side project, “Walking with Rachel Carson’s Letters.” It’s a blog about my reading of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman’s love letters to each other while I train for a hiking event held on the Rachel Carson Trail just outside Pittsburgh.

Pamela VanHaitsma is a Sherwin Early Career Professor in the Rock Ethics Institute and an assistant professor of Communication Arts & Sciences and Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies at Penn State University, where she also serves as interim director of the Center for Humanities & Information. She is the author of Queering Romantic Engagement in the Postal Age: A Rhetorical Education (2019). Her work also has appeared in the journals Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Quarterly Journal of Speech, Advances in the History of Rhetoric, Rhetoric & Public Affairs, and QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, among others.

Pamela VanHaitsma is a Sherwin Early Career Professor in the Rock Ethics Institute and an assistant professor of Communication Arts & Sciences and Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies at Penn State University, where she also serves as interim director of the Center for Humanities & Information. She is the author of Queering Romantic Engagement in the Postal Age: A Rhetorical Education (2019). Her work also has appeared in the journals Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Quarterly Journal of Speech, Advances in the History of Rhetoric, Rhetoric & Public Affairs, and QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, among others.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com