Jo Somerset

If Napoleon Bonaparte considered Britain a nation of shopkeepers, I don’t think he meant Morley Clarke and Roland Spence – a tailor and a bookseller in Leicester. Morley died in 2010, aged 93, and by accessing his artefacts I’ve traced their joint life, which typifies gay men’s experience in the twentieth century: a shameful secret hidden from family, underground socialising, fear of arrest and public outing. But I also found the joy of burgeoning love, self-expression through amateur theatre and making drag gowns.

As a feminist historian, I read against the grain to glean buried facts. As a lesbian, I’m learning to queer history, to decipher coded messages and read between the lines. To fill the gaps in LGBTQ+ history, I borrow from Toni Morrison’s technique of ‘rememorying’. Just as she re-membered lives of enslaved people whose bodies and selfhood had been pulled apart, I too create stories where none had existed. But my stories are history, not fiction.

To depict the LGBTQ+ past may involve provocative assertions while assembling facts that don’t quite add up. I felt like an intruder winkling out facts from this family, rooting through Roland’s writings and the lives of myriad Clarke ancestors, half-siblings and cousins. As I fished around the lives of these two very private men, I had to speculate to understand photographs, letters, a tailor’s ruler and a mysterious telegram. Roland’s diaries, though full of words, leave so much unsaid.

In How to Read a Diary (2019), Desirée Henderson writes about the ‘gender paradox’ whereby diaries’ usefulness is defined by sexist and patriarchal definitions of what is important: world events, political developments, movements or royalty and famous people. While on the one hand diaries are belittled as a feminine pastime, on the other they are lauded if written by someone famous (read: famous Western man). Diaries are beginning to have their moment, particularly in telling untold stories of ‘little’ people whose lives are deemed unimportant, or, more likely in the LGBTQ+ context, hidden.

Roland’s diaries run across the decades and reflect the times. In 1935, aged seventeen, taking ballet lessons was a deathly secret, and it was difficult for Roland to practice. ‘I wish everybody knew, then I could do it!’, he writes. Later, I like to imagine a frisson between the two thirty-somethings at a suit fitting. By 1949 they were a couple.

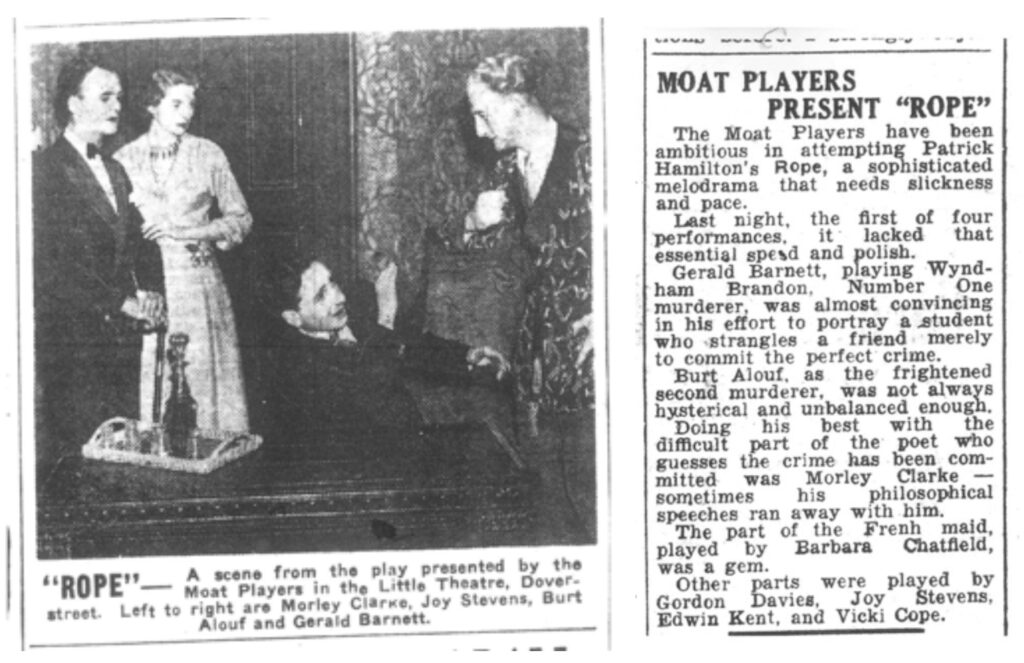

They probably met at the Leicester Amateur Dramatic Society (LADS) based at the Little Theatre, where they briefly knew Joe Orton, an openly gay playwright who later achieved notoriety for his outrageous black comedies which were part of the British working-class theatre revolution of the 1960s. Theatre was their shared passion. The teenage Roland had been so overcome by seeing the divine – to use one of his favourite camp adjectives – Ivor Novello perform in London that it was four days before he ‘just about recovered from the effects.’ Having somewhere to be free in body, mind and spirit must have been a heady mixture in those times. A backstage photo of seven men smiling at the camera, arms around each other’s shoulders or sitting between the knees of the man behind, shows a warm camaraderie amongst the cast. After-show parties spilled over into the Dover Castle across the road – possibly the UK’s oldest gay pub.

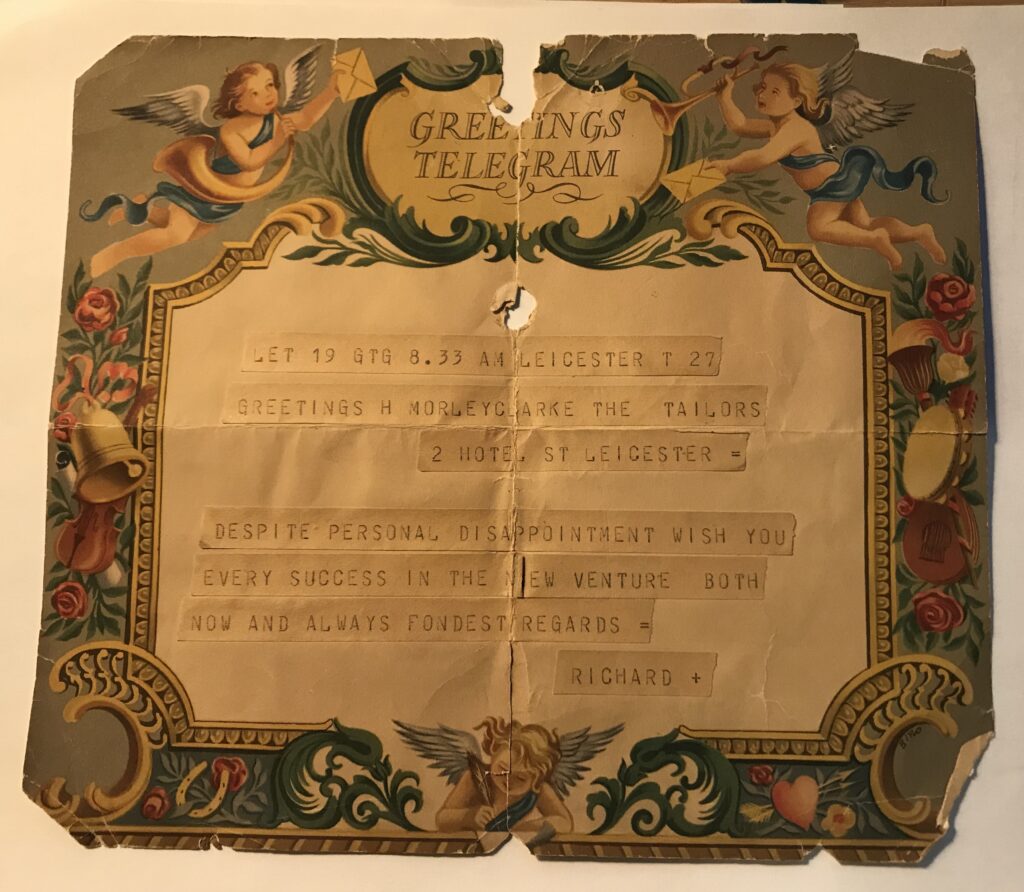

In 1955, a shop sign at 2 Hotel Street declared Morley’s shop “HM Clarke, Ladies and Gents TAILOR” open. Meanwhile, Roland was running a bookshop three doors away. At the opening of his shop, Morley received a telegram: “DESPITE PERSONAL DISAPPOINTMENT WISH YOU EVERY SUCCESS IN THE NEW VENTURE BOTH NOW AND ALWAYS FONDEST REGARDS RICHARD”. We can only guess who Richard was. It reads like a note from a previous employer, but the tone suggests far more. I suppose, in a small city like Leicester, where what we now call the ‘gay community’ was well-represented by the ‘camp’ professions – actors, hairdressers, chefs and tailors – everyone knew each other, forging tight relationships. The secret knowledge of your colleagues’ sexuality would most likely have endowed an extra bond of fondness.

In 1959, together now for ten years, Roland experienced an inner turmoil that was common amongst gay men forced to live secret lives. He could not verbalise in his diary what he called ‘the problem’, using a metaphor of imprisonment: ‘There seems no end to the problem –….one’s own mind closing one in within one’s own four cell walls’. He reveals disturbing self-loathing: “Mill around in a stinking black pit!” Roland baulks in the diary at his ‘dear lad’, Morley, who considers them ‘fortunate’: ‘[W]e haven’t been!’, he asserts, ‘That we have made the most of what we have had is possibly true, but this does not mean we have had more than our measure.’

Their love story is marred by Morley’s devotion to his mother. Roland was desperate for Morley to leave his mother’s house, but he only dared mention it as a ‘dream’. In reality, they had to wait another twelve years. She died in 1971, and after 22 years together they could finally have the lovers’ life they’d yearned for. Their house in Narborough became notorious for parties where Morley was the giggly, funny one, while Roland was more serious. They lived in a ‘glass closet’ where no-one mentioned that they were a couple, but everyone knew; a scenario that many will still recognise.

By the 1980s, despite their old-fashioned elegance, Morley and Roland had moved with the times. Roland’s 1982 diary, written in hospital, mentions Morley confidently and openly. No longer tortured by the ‘problem’, he’s occupied instead with paying his own mother’s bills and locating his razor. His writing bubbles with innuendo. ‘Who could resist “battered sausage”?’ for dinner, he asks. And when his groin was shaved pre-op, he relays how ‘Fred arrived with his cut-throat razor and a glint in his eye.’

Their love story ended in tragedy, however, when Roland died in hospital aged 65. His family swooped, taking what they liked from Morley and Roland’s home, totally ignoring their relationship – the one everyone knew but no-one mentioned. Morley was finally outed posthumously at his funeral tea in 2010 at the hotel where the ‘homosexuals’ used to gather, because the collection was in aid of Stonewall.

At a time when most British LGBTQ+ history is located in London, unearthing a story from the East Midlands enriches our bank of twentieth-century knowledge. Roland and Morley’s story, set firmly in Leicester’s traditional clothing industry, its geography and cultural institutions, adds texture to heretofore London-centric accounts of LGBTQ+ pasts. Shining a light on two gay men’s experience highlights a fountain of flamboyant resistance outside the capital. Holiday photos, artefacts and family feeling come together to re-make, re-member and honour a gay couple in a way that could not happen during their lifetimes.

Jo Somerset (she/her) is a Manchester-based writer and historian. Her word portraits highlight a personal connection to stories that she uncovers from the past, most recently featuring in LGBT History Month 2021. In 2020 she won the Leanne Bridgewater Award for Innovation and Experiment at Salford University, where she completed a MA in Creative Writing. Her research has been published in the European Journal for Life Writing and Northern History. Jo’s historical nonfiction appears in Queerlings, Clavmag, and Another North. She’s contactable on her website or Twitter @josomerset

Jo Somerset (she/her) is a Manchester-based writer and historian. Her word portraits highlight a personal connection to stories that she uncovers from the past, most recently featuring in LGBT History Month 2021. In 2020 she won the Leanne Bridgewater Award for Innovation and Experiment at Salford University, where she completed a MA in Creative Writing. Her research has been published in the European Journal for Life Writing and Northern History. Jo’s historical nonfiction appears in Queerlings, Clavmag, and Another North. She’s contactable on her website or Twitter @josomerset

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com