Moderated by Lina-Maria Murillo, edited by Desiree Abu-Odeh

This is Part 2 of a two-part roundtable. Part 1 was published on March 22, 2022. In this installment, Rachell Sanchez-Rivera, Natalie Lira, and Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci continue the discussion about how white supremacist ideologies have shaped conversations about demographic changes and immigration, and how those conversations have shaped nationalist and fascist state projects globally.

Rachell Sanchez-Rivera

To what extent have white supremacist and/or nationalist ideologies shaped historical conversations about demographic changes (particularly declining birth rates) and immigration concerns globally?

Nationalistic ideologies that privilege the ‘Mexican nation’ as a ‘mestizo nation’ are intertwined with the development of eugenics and whiteness as an organising principle. For instance, after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), eugenicists in Mexico argued that Mexico’s demographic problems could only be solved through the rational reproduction of people for the betterment of the nation. This relied on myths around Mexican mestizaje as a national trope, i.e., white men “mixing” with indigenous women—as the latter were thought of as ideal passive reproductive subjects who were intrinsically monogamous. In this sense, everything outside of this specific ‘type’ of coupling became Other and, therefore, not part of the nation. Attempts to make a ‘desirable’ mestizo were seen in migratory policies, the compulsory production of marriage certificates (that in the case of Mexico were enacted after 1935 and still exist in some cases today), and even sometimes through cultural events and beauty pageants.

Mexican anthropologist Manuel Gamio dedicated an entire chapter of his book Forging a Nation (1916) to women, entitled “Our Women”—which suggested, in a patronizing way, that women were, in a sense, a kind of national property. In this chapter, he classified and divided women into three implicitly racialised categories: servant, feminist, and feminine (Gamio, [1916] 2010, p. 115–125). Gamio argued that feminine women were the most desirable of the three, as they still held notions of honourability and purity that would make for a desirable additive to the existing races in Mexico. This category aligned with myths of indigenous women as traditional, passive, monogamous, and pure. Conversely, in Gamio’s view, feminists had masculine traits like modern, short haircuts which contrasted with the traditional long hairstyles of indigenous women who still preserved their traditions of purity and morality. His “feminist” category mapped onto the chica moderna (modern woman), who was not indigenous but an acculturated criolla (lighter skinned woman with Spanish lineage). The chica moderna was thought to bring with her feminist ideas, including the control of reproduction, which was at odds with pronatalist ideologies and therefore jeopardized reproduction of the mestizo and the making of a mestizo nation.

Gamio worked to make indigenous women desirable to white men as a way of (1) putting into practice the ideas discussed in Forging a Nation, and (2) making Mexico a mestizo nation. In order to do this, he organized the beauty contest titled ‘la india bonita’ (translated to: the beautiful Indian) in 1921. The contest’s judges were well known to the Mexican people, including organizer Gamio. And the contest’s outcome and images were published in El Universal, a widely read national newspaper in Mexico. By portraying the winner of the pageant, María Bibiana Uribe, as a ‘pure race meshica indian,’ Gamio presented her as an exotic indigenous woman with a glorious lineage that could be traced to courageous warriors, depicting Uribe and women like her the ideal women for mestizaje. Additionally, the idea that someone—in this case an indigenous woman—from within the Mexican nation could be exotic is telling as it places her in contrast with the chica moderna.

How have those conversations shaped nationalist and/or fascist state projects that regulated and otherwise controlled people’s reproduction and sexuality?

After the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), different institutions and state services were dedicated to the reconceptualization of motherhood and puericulture—the care of children—under the banner of “la gran familia Mexicana,” or the grand Mexican family. The term la “gran familia Mexicana” in fact originated in the nineteenth century as a popular saying that fed different political rhetoric and referred to being naturalized and accepted as a citizen of Mexico. This concept of “la gran familia” stemmed not only from the processes of naturalization, but also from the fact that most migrants seeking naturalization had already built a life in Mexico and did not have any plans to return to their countries of origin. The notion of a grand Mexican family is critical to understanding Mexican nationalism in the post-revolutionary period.

According to Mexican eugenicists, the rational mixing of the population would lead to happy and normal children. Nonetheless, this could come at the expense of the happiness of those heterosexual parental figures that decided to make the eugenically rational decision to mix for the betterment of mestizaje. The eugenically ideal role of men in Mexico was to be somewhat absent from raising children and caregiving. Eugenicists in Mexico believed that men should be, above all, sober, industrious, and clean. However, in reality, it was women who were often charged with the job of keeping men away from alcohol, for example, instead of appealing directly to the responsibility of men.

Perpetual Secretary of the Mexican Society of Eugenics (MSE) Alfredo Saavedra argued that, despite supporting women’s empowerment and the chica moderna, it was important to keep a traditional patriarchal structure in Mexico. For instance, one can observe the paradoxical elements of Mexican eugenics between the figure of the chica moderna and mujer decente (decent or good woman) when Saavedra argued that the “first step of female liberation, motivated by the incentive of the species, [entailed] not worrying about the interests of the father.” For Saavedra, the roles of men and women were dictated by biology. In his view ‘women had to be fundamentally feminine, and men had to be essentially masculine with all the attributes and obligations that emerge from their somatic constitution.’ Thus, we can observe here the ways in which eugenicists made use of biological and anatomical conceptions to support changing political and social conventions and ground Mexican nationalism in traditionalist views about the family.

Part of the goal of this roundtable is to bring together historians focusing on the intersecting themes mentioned above. For those in our audience who are interested in learning more or teaching this history, could you recommend one or two key texts to better understand the material presented here?

For those interested in learning more about this history, here are my recommendations for further reading: Alexandra Stern’s “Eugenics in Latin America,” (2016) and “Responsible Mother and Normal Children: Eugenics, Nationalism, and Welfare in Postrevolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940” (1999); Nancy L. Stepan’s classic The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender, and Nation in Latin America (1991); as well as my article, “The Making of La Gran Familia Mexicana: Eugenics, Gender, and Sexuality in Mexico” (2021).

Natalie Lira

To what extent have white supremacist and/or nationalist ideologies shaped historical conversations about demographic changes (particularly declining birth rates) and immigration concerns globally?

White supremacy and nationalist ideologies have been at the heart of both political debates and research regarding demographic changes and immigration in the United States. One clear example of this is the American eugenics movement of the late 19th and 20th century. At its core, eugenics was an effort to use science to support the political and reproductive power of “fit” populations while preventing the growth of purportedly “unfit” populations. Eugenicists asserted that properly managing birth rates and demographic changes along lines of racial fitness was a necessary political, economic, cultural, and social endeavor and one that the state had a right to implement. Shaped by ideologies of white supremacy, eugenic notions of fitness correlated strongly with already existing racist, sexist, ableist, and classist hierarchies. As a result, eugenicists endorsed policies and practices that encouraged and supported the reproductive and family-making efforts of white, middle and upper-class, able-bodied people. At the same time, they devised a plethora of approaches to restricting the reproduction and family formation of the “unfit” most of whom were low-income, disabled, racialized, gender non-conforming or otherwise categorized as outside of the white-middle-class, able-bodied ideal.

Eugenics strongly influenced immigration debates in the 1910s and 20s. Alarmed by the influx of immigrants eugenicists deemed racially inferior and “degenerate”–namely those from Eastern and Southern Europe and Mexico– American eugenicists like Madison Grant and Harry H. Laughlin rallied the public and Congress around immigration restriction. Both published studies demonstrating the risk that “Native” American (aka Anglo-Saxon) bloodlines faced amid unregulated immigration. In his “The Passing of the Great Race,” Grant quite literally asserted that the “Nordic race”–and thus superior white civilization– risked extinction. Laughlin commissioned studies that supposedly proved the racial and social inferiority of racialized immigrants and successfully convinced Congress to limit the number of “undesirable” immigrants allowed into the United States through the 1924 Immigration Act (Johnson-Reed Act).

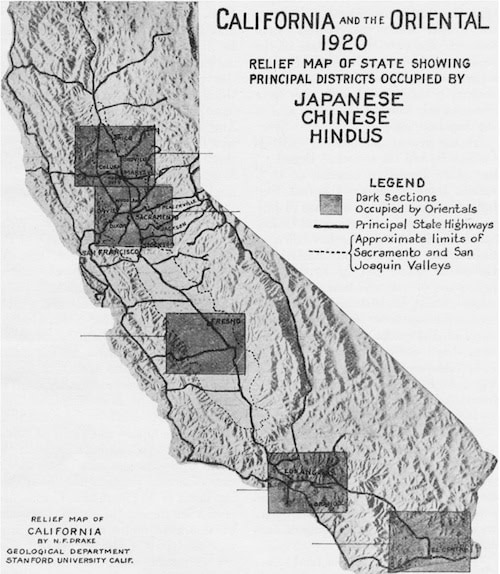

Immigration restriction was just one outcome of eugenicists’ racist framing of immigration and demographic changes. This framing also pervaded the way state and local agencies viewed and treated immigrant communities. For example, in the 1920s, Los Angeles Public Health workers often expressed concern over the declining birth rates among Anglo-Americans in comparison to what they asserted was the hyperfertility of Mexican-origin communities in the area. This not only posited Mexican-origin communities as a “racial problem” but also shaped views of them as inherently foreign and therefore undeserving of state services. This racist framing situated the needs of Mexican-origin people and communities as an undue burden on the state, which justified neglect, discrimination, poor quality services, deportations, and other invasive and violent interventions, including forced sterilization.

How have those conversations shaped nationalist and/or fascist state projects that regulated and otherwise controlled people’s reproduction and sexuality?

Eugenics influenced a host of state policies aimed at regulating and controlling people’s sexual and reproductive lives, including state-imposed marriage restrictions, the general policing of people’s sexual lives, and the confinement of people deemed “unfit” into state-run institutions through their years of reproductive potential. One of the most violent ways that eugenics shaped state interventions on people’s reproduction was by legitimizing state-mandated sterilization as a public health measure. After eugenic sterilization was legitimized by the Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell (1927), 32 states passed eugenic sterilization laws. Under these laws, approximately 60,000 people were sterilized because they were deemed “unfit” to reproduce.

Eugenic criteria for sterilization, grounded in ableist notions of biological and hereditary fitness, played out in ways that were specific to each state’s social and demographic context. In North Carolina, where the state’s eugenics board approved sterilizations into the 1970s, Black women were targeted for the surgery. In Iowa, low-income white people and some European immigrants were targeted. In my work on eugenic sterilization in California, I demonstrate how ideologies of race, disability, and gender converged, resulting in the disproportionate institutionalization and sterilization of Latinx people—youth in particular. Eugenic sterilization was also implemented in Puerto Rico, where concern was not explicitly “unfit” populations, but sterilizations were encouraged under the guise of population control and “overpopulation” that was blamed on low-income Puerto Rican women’s reproductive behaviors.

While most states either repealed eugenic sterilization laws or stopped practicing state-mandated sterilization, sterilization abuse continued into the late 20th century and persists today–well beyond what is officially recognized as the eugenics era. In the 1960s and 70s, racist and paternalistic physicians working in public-serving hospitals sterilized low-income and women of color in cities like Los Angeles and New York, and in Indian Health Service facilities. In these cases, racism converged with population control efforts to legitimize the use of federal family planning funds that paid for forced and coerced sterilizations in county hospitals and Indian Health Service facilities. In the 2000s, state funds were misused by California state officials to perform unwanted sterilizations on incarcerated women. Most recently, a whistleblower revealed that medical staff in a Georgia ICE facility were subjecting immigrant women to unwanted hysterectomies. While these sterilizations did not occur under eugenic laws or explicit state policy, they represent the ongoing legacy of eugenics and the continued eugenic effort to violate the reproductive autonomy of populations deemed “unfit.”

Part of the goal of this roundtable is to bring together historians focusing on the intersecting themes mentioned above. For those in our audience who are interested in learning more or teaching this history, could you recommend one or two key texts to better understand the material presented here?

Douglas Baynton’s Defective in the Land (2016) and Jael Silliman et al.’s Undivided Rights (1st edition 2004, 2nd edition 2016) are excellent and have helped me immensely as I teach this critical history of eugenics and reproduction in the US. My recently published book, Laboratory of Deficiency (2021), analyzes the brutality of eugenic sterilization regimes through the lens of reproductive justice and disability studies.

Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci

To what extent have white supremacist and/or nationalist ideologies shaped historical conversations about demographic changes (particularly declining birth rates) and immigration concerns globally?

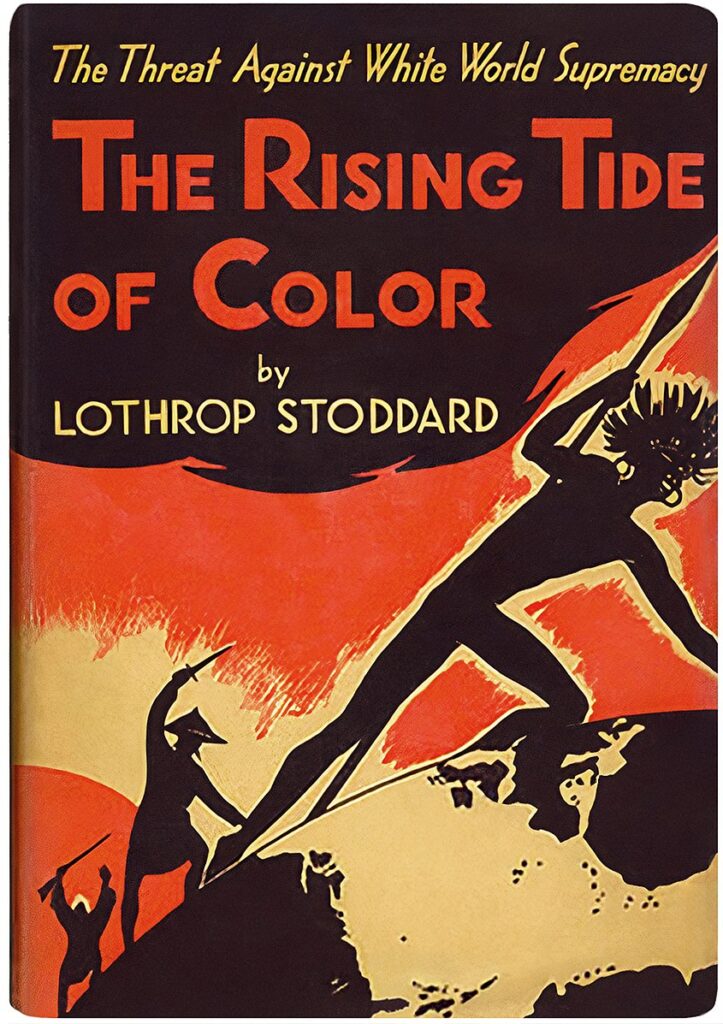

The eugenic, race-based fear, is very well illustrated in the popular book written by Harvard-educated social scientist, Lothrop Stoddard, published in 1920, called: The Rising Tide of Color Against White-World Supremacy. There were other influential books written by eugenicists at the time, such as Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916). The common fear that was expressed in these writings was the threat of new immigrants. Eugenicists often blamed immigrants from southern and eastern Europe for deteriorating the quality of Americans. As Asian (in particular, Japanese) immigration increased in California, this became an even bigger concern for them. In the case of Asian immigrants, assimilation into the American “melting pot” was not even a possibility, and therefore, the imagined scenario was that Asian immigrants would gradually replace the white population through their “excessive” birth rates. This eugenic argument played an instrumental role in the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, which deemed Asian immigrants as “unassimilable” and therefore excluded them from immigration quotas.

Stoddard’s book further linked these eugenic fears to global politics. He was particularly alarmed by Japan’s rising military power, as marked by its victory over Russia—a “white” nation—in the 1904-5 Russo-Japanese War. According to Stoddard, World War I—what he called the “White Civil War”—further opened up possibilities for the colored races to revolt against “white-world supremacy.” The fact that Stoddard’s warning about the “rise of the colored empires” appeared in the famous novel Great Gatsby shows how influential his theory was at the time, especially among the elite circles.

Wikimedia Commons.

The idea of the “swarming” people of color taking over the world through immigration and high birth rates—the demographic “Yellow Peril”—was further solidified by “population scientists” in the 1930s. According to Warren Thompson’s Danger Spots in World Population (1929), Japan’s overpopulation problem was a threat to world stability because it caused the small island nation to expand abroad for more territory and resources to feed its people. These scholars claimed scientific objectivity and impartialness in their studies, but they were basically repeating the same-old eugenic, race-based anxieties. These ideas justified western intervention in fertility control in other, mostly non-western, non-white nations in the post-World War II era, when the world became preoccupied with the threat of a “population explosion.”

How have those conversations shaped nationalist and/or fascist state projects that regulated and otherwise controlled people’s reproduction and sexuality?

What’s fascinating about the eugenics movements of the early to mid-twentieth century is how widespread and influential they were, globally. While American eugenicists warned of the swarming people of the East, the Asian states also adopted eugenic policies that they had learned from or had been inspired by the West. For example, some of the first sterilization laws in the world that were implemented in the United States, especially the one in California, inspired the forced sterilization program carried out by the Nazi regime in 1933; and the Nazi law, in turn, became the model for the 1940 National Eugenic Law in Japan.

It’s important to note that these state eugenic policies were not just about sterilization laws—often described as “negative” eugenics (i.e. limiting the birth of certain people). Rather, in many cases, the state put more emphasis on “positive” eugenic measures—pronatalist policies (for certain people) in the form of financial incentives, childcare support, and other propaganda activities. Especially during the war years, the focus of the National Eugenic Law in Japan was more on pronatalism, to the extent that many of the “negative” measures such as sterilization and marriage restrictions against those deemed “unfit” were not actually implemented. It was after World War II, when the government shifted its position from pronatalism to (temporary) population control to deal with the postwar social and economic crises, that the negative measures were strengthened through the 1948 Eugenic Protection Law.

Many elite leaders, whether in Japan or the United States, hesitated to openly endorse birth control until around the 1940s. They were more worried that the practice would be used by their own women (white and/or middle class), and not by those who really “needed” it. When “birth control” became “family planning” or “planned parenthood,” shedding the earlier radical images associated with feminist leaders such as Margaret Sanger, political leaders and intellectuals gradually came to endorse the concept. Even then, birth control advocacy was mostly directed toward “other” women—i.e. women of lower classes, women of color, women in Third World countries. On the other hand, the concept of “family planning” was more readily accepted by leaders as a national policy because it sounded broad enough to include “positive” eugenic measures.

Part of the goal of this roundtable is to bring together historians focusing on the intersecting themes mentioned above. For those in our audience who are interested in learning more or teaching this history, could you recommend one or two key texts to better understand the material presented here?

The details of what I explained above are all in my book, Contraceptive Diplomacy: Reproductive Politics and Imperial Ambitions in the United States and Japan. Sabine Früstrück’s Colonizing Sex: Sexology and Social Control in Modern Japan and Tiana Norgren, Abortion before Birth Control: The Politics of Reproduction in Postwar Japan are also excellent books to learn about the history of reproductive politics in Japan.

I also find Ayça Alemdaroğlu’s work on eugenics in modern Turkey fascinating and see many parallels with the eugenic policies in Japan that were implemented since the establishment of the modern state. Turkey is another non-western model of modernization that took place in the early twentieth century, during which eugenic thoughts were used as the core of nation-building and race improvement.

For the American side of story, especially in connection to eugenics, gender, and pronatalism, I would recommend Laura Lovett’s Conceiving the Future: Pronatalism, Reproduction, and the Family in the United States, 1890-1938, and Wendy Kline’s Building A Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom.

Rachell Sanchez-Rivera is a Research Fellow at Gonville & Caius College and an Affiliate Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Cambridge. Before this, they were a Postdoctoral Fellow funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge. They completed their PhD in the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge in December 2019. Their areas of expertise are in critical race theory, the critical study of eugenics and scientific racism, historical sociology, and the sociology of health and illness with a focus on reproduction, decolonial theory, gender studies, queer theory, and social inequalities. They tweet from @RSanchezRivera1

Rachell Sanchez-Rivera is a Research Fellow at Gonville & Caius College and an Affiliate Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Cambridge. Before this, they were a Postdoctoral Fellow funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge. They completed their PhD in the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge in December 2019. Their areas of expertise are in critical race theory, the critical study of eugenics and scientific racism, historical sociology, and the sociology of health and illness with a focus on reproduction, decolonial theory, gender studies, queer theory, and social inequalities. They tweet from @RSanchezRivera1

Natalie Lira is an interdisciplinary scholar and Assistant Professor of in the Department of Latina/Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. She earned her PhD in American Culture from the University of Michigan. Her research interests include the politics of reproduction, histories of medicine, and the ways that struggles for racial and reproductive justice intersect. She is an expert on eugenic sterilization, co-director of the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab, and author of the book Laboratory of Deficiency: Sterilization and Confinement in California, 1900-1950s (University of California Press, 2021). She tweets from @ProfLiraN

Natalie Lira is an interdisciplinary scholar and Assistant Professor of in the Department of Latina/Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. She earned her PhD in American Culture from the University of Michigan. Her research interests include the politics of reproduction, histories of medicine, and the ways that struggles for racial and reproductive justice intersect. She is an expert on eugenic sterilization, co-director of the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab, and author of the book Laboratory of Deficiency: Sterilization and Confinement in California, 1900-1950s (University of California Press, 2021). She tweets from @ProfLiraN

Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci (PhD in American Studies, Brown University) is Assistant Professor and Co-Director of the Center for Asian Studies (KUASIA) at Koç University. Her book, Contraceptive Diplomacy: Reproductive Politics and Imperial Ambitions in the United States and Japan (Stanford University Press, 2018), won the John Hall Whitney Book Prize from the Association for Asian Studies. Her work centers around the trans-Pacific politics of birth control and eugenics.

Lina-Maria Murillo is an Assistant Professor of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies, History, and Latina/o/x Studies at the University of Iowa. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Fighting for Control: Power, Reproductive Care, and Race in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (UNC Press). She examines the tensions between advocates for population control and those committed to greater reproductive access for the majority Mexican-origin women in the borderlands. She tweets from @LinaMariaMuril6

Lina-Maria Murillo is an Assistant Professor of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies, History, and Latina/o/x Studies at the University of Iowa. She is the author of the forthcoming book, Fighting for Control: Power, Reproductive Care, and Race in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (UNC Press). She examines the tensions between advocates for population control and those committed to greater reproductive access for the majority Mexican-origin women in the borderlands. She tweets from @LinaMariaMuril6

Desiree Abu-Odeh recently earned her PhD in Sociomedical Sciences from Columbia University, where she focused on the history and ethics of public health. Her dissertation examines the emergence of what is now known as “sexual violence” and responses to it on American college campuses from 1952 to 1980. Her research interests include histories of gender, race, sexuality, and social movements in the United States. Her work has been published in Social Science History, American Journal of Public Health, and Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal.

Desiree Abu-Odeh recently earned her PhD in Sociomedical Sciences from Columbia University, where she focused on the history and ethics of public health. Her dissertation examines the emergence of what is now known as “sexual violence” and responses to it on American college campuses from 1952 to 1980. Her research interests include histories of gender, race, sexuality, and social movements in the United States. Her work has been published in Social Science History, American Journal of Public Health, and Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com