In an earlier posting on NOTCHES, Kim Racon draws attention to the case of John Rykener, dubbed the ‘male transvestite prostitute’ by David Boyd and Ruth Karras. Her discussion of this 1394 case from the London Plea and Memoranda Rolls, which minute the business of the mayor’s court, considers its implications for our understanding of gender and sexuality in the age of Richard II. She notices how Rykener presented her/himself as an embroideress whilst staying in the university town of Oxford and as a barmaid of the Swan during her/his time in the small, but thriving wool town of Burford, occupations commonly employing women. She also highlights how clergy were prominent among Rykener’s clients in her/his capacity as a sex worker providing sexual services ‘in the manner of a woman’.

Kim Racon locates the gender-crossing Rykener in the dynamic and sometimes tumultuous environment of the later fourteenth century. This was a society and economy transformed by the devastating mortality heralded by the Black Death, itself understood as divine judgement and punishment for sin. The ruling elite was unsettled by both social change and the perception of social change, which they understood in moral terms. All deviations from the supposedly divinely sanctioned social and gender order were consequently understood as manifestations of sin that needed correction. London’s civic governors shared this perception which some of the themes raised by the Rykener case echo. Two particular targets of city government are prominent. One were clergy who preached sexual morality, but are shown to be entirely devoid of moral authority by their actions. By highlighting their failings, city magistrates implicitly asserted their own moral authority.

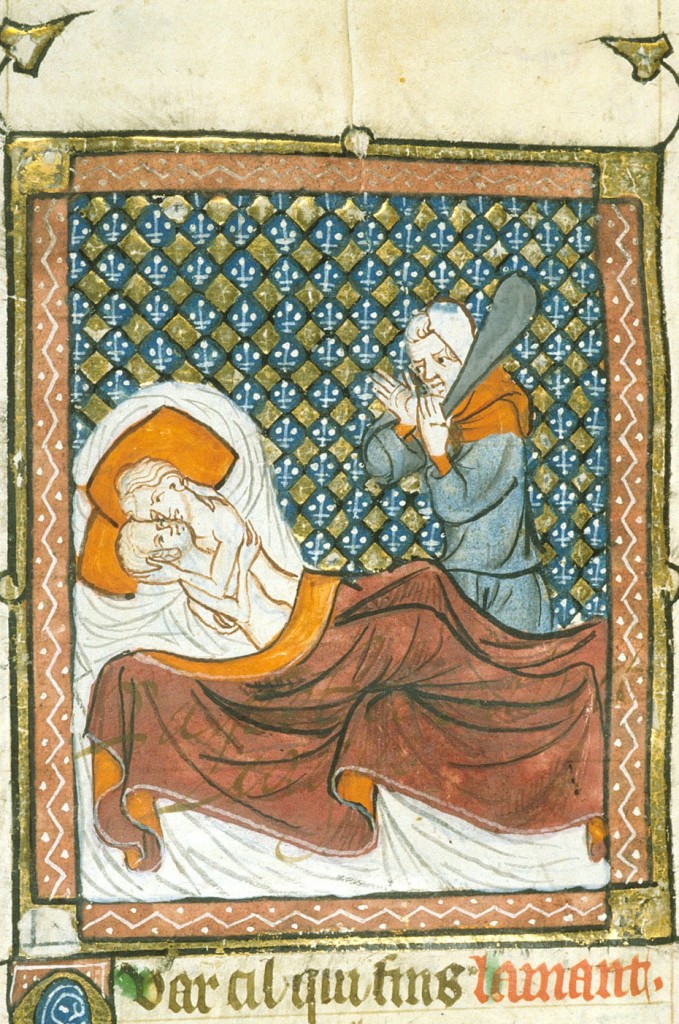

The other target was dishonest trading. Rykener claims he was first dressed in women’s clothes by Elizabeth Brouderer (i.e. Embroideress), who can be identified with Elizabeth Moring, embroideress, noted in another case a decade earlier. She used her embroidery business to recruit unsuspecting girls as apprentices whom she subsequently prostituted. In the present case Elizabeth allegedly prostituted her own daughter, but substituted Rykener in the bed during the night to blackmail clients the following morning by making them believe that they had in fact slept with a man. The deception was taken further by another woman, called Anne, who instructed Rykener how to have sex with men ‘modo muliebri’ – ‘in the manner of a woman’. The narrative of the record tells of male customers seeking to purchase sex from a woman, but deceived into having sex with a man masquerading as a woman, just as it references another woman who purported to run a legitimate business, but in fact ran a prostitution racket. Women here are thus very much implicated in dishonest trading.

Absent from previous writing on the Rykener case is discussion of its historicity. It has implicitly been assumed to be a trustworthy record of an actual case involving the cross-dressing Rykener and his unwitting client, a Yorkshireman with the no-less unusual name of Britby. Certainly as a court record it is correctly entered in the Plea and Memoranda rolls on the right roll for the date of the case. (In fact its position with one other curious case on a new piece of parchment is odd.) On the other hand, the record ends abruptly without any verdict or record of punishment – not of itself particularly remarkable – nor is there clarity as to what, if any, charge applied. Even that, given the extraordinary nature of the case, need hardly be an objection. (Prostitution was not normally a matter for the mayor’s court and sodomy, not yet a felony, more obviously belonged to the Church courts.) Much more puzzling is how comparatively detailed the account is despite most of the information recorded relating to events in Oxford, Burford, Beaconsfield and the lanes outside St Katherine’s Hospital, beyond the walls to the east of London. There is no good reason for the court to be interested in what allegedly happened in these places which fell outside its jurisdiction, nor for the clerk to expend unnecessary time or parchment providing a record in Latin.

The historicity of the two principal actors can be tested. A John Britby was later the vicar of a poor and obscure Yorkshire parish and a John Rykener, clerk, escaped the bishop of London’s prison at Bishop’s Stortford in 1399. We cannot know that these are the same men, but the dates fit and the names Britby and Rykener are otherwise virtually unknown despite a wealth of extant documentary evidence. As noted, Elizabeth Brouderer may be the same person as Elizabeth Moring. Sir (the courtesy title for a priest) William Foxlee, one of Rykener’s Oxford clients, may have been the New College chaplain recorded some years later. However, the phrase ‘Anne, the late whore – the Latin appears deliberately pejorative – of an employee of Sir Thomas Blount’ seems an elaborate and pointless way to identify the woman called Anne who instructed Rykener how to have sex as a woman. Elaborate because it uses eight words of Latin where most people are identified in two and pointless because as the late – I think the implication of the Latin is that she is now dead – mistress of an unnamed employee of a man who probably had numbers of employees, she is in fact effectively unidentifiable. The employee’s name is the crucial identifier, but it is only the employer, Sir Thomas Blount, that is named.

Sir Thomas is not just another knight in an era of lords and knights. He was a man who had risen to prominence in the service of Richard II. Earlier that year he had married a wealthy widow, so gaining lands to match his status at court. His inclusion in the narrative is significant because gratuitous. It is one of a number of factors that prompts doubts as to how far this text is what it purports to be. Another is the timing of Rykener’s alleged transgression and arrest. The Sunday night in December 1394 was the day after the City of London loaned several thousand pounds to Richard II, a huge sum they would not have expected to be repaid since Richard was better known for extracting money than repaying debts.

Why was London prepared to make such a loan and what has this to do with Rykener? Relations between the city and its capricious monarch were highly strained. In June 1392 Richard II had taken the city into his own hands, appointing a governor in place of the elected mayor. The ostensible reason for this precipitate and high-handed action was that the mayor and aldermen had supposedly failed to keep good order and were guilty of bad governance. The suspicion was that Richard was venting anger at Londoners’ reluctance of to lend him money. Some months later Richard and the city were reconciled and the city’s constitution was restored following an elaborate ceremony culminating in Richard being crowned by a youth representing an angel on the city’s principal thoroughfare of Cheapside. In fact Richard was paid a very large sum of money and the constitution was only conditionally restored. Should Richard have any reason for dissatisfaction with how London was governed, he reserved the right immediately to resume control. Until full restoration in 1397, London and Londoners lived in fear of retribution. Requests for ‘loans’ had to be met. No hint of dissent was permissible.

To condense my argument in the new issue of Leeds Studies in English, the Rykener case gives voice to dissent in the form of political satire, but disguised, just as Rykener was disguised, as court record. The motif is governance rather than sex, but the regulation of sex served as a metaphor for good governance. Outside London’s jurisdiction, Rykener violates sexual norms with impunity. S/he has paid sex as a woman with numerous friars, secular clergy, Italian merchants and the like, but also as a man seduces one man’s daughter and has sex with lots of nuns, married women and single women. When Rykener enters the City’s jurisdiction and is solicited by John Britby he is immediately arrested, imprisoned and brought before the mayor’s court. The message is clear. Good governance is found in the City. Bad government lies outside.

Each of the locations Rykener visited is significant. Burford references one of Richard’s favourites, Thomas Despenser who achieved his majority the same year as the case and so inherited the lordship of Burford among many possessions. Despenser, through his seigneurial court, thus governed this apparently lawless Cotswold boom town in which Rykener the barmaid sold sex to the patrons of the Swan. Oxford perhaps references Richard’s exiled and deceased favourite Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford. More immediately it references the issue of governance. Oxford’s constitution was modelled on London’s, but since rioting in 1355 the crown had awarded the university’s chancellor control of all matters pertaining to the university, its students and employees. Here Rykener traded as an embroideress whilst selling sex with impunity to scholars of the university.

Rykener’s final destination on his return to London following his jaunt into the Cotswolds is especially telling. Rykener confessed to having, in modern parlance, gay sex with three chaplains, described with ostentatious euphamism in the record. The location was the lanes outside St Katherine’s Hospital, a royal foundation under the patronage of the queens of England. The area was bounded to the north by the royal monastery of St Mary Graces and to the west by the royal palace of the Tower of London. Were this a record of actual events, returning by a circuitous trip to this royal enclave outside the City would seem bizarre. As part of a political satire it makes sense. Prostitution as an outlet for sexual desire was deemed tolerable if it could prevent the greater evil of sodomy, understood as sexual activity, including anal sex, other than ‘natural’ penetrative, straight sex. Theologians held that good sewers characterised the well-ordered palace. Without sewers, effluent would flood the palace, which would in time spill beyond the palace. London, as well-governed city, maintained good sewers: prostitution was forbidden within the city walls, but in Cock’s Lane or across the Thames in Southwark it was permitted. When Rykener takes his client down Soper Lane and commences to have sex over one of the stalls there, the two are promptly arrested even though the City officers did not then know that Rykener was not a woman. Outside London where properly constituted civic government was muzzled (Oxford), or where aristocracy exercised inherited authority (Burford, Beaconsfield) sexual deviancy was practised with impunity. In the lanes outside St Katherine’s Rykener was buggered by three chaplains. The sewers in the adjacent palace were demonstrably defective. Effluent spilled out beyond the City walls.

By naming Sir Thomas Blount and alluding to other royal favourites, the narrative takes us to the court of Richard II. The Tower of London as the palace without sewers also alludes to the royal court. The (now deceased) Anne who first instructed Rykener takes us closer to Richard himself. In 1394 Anne was still a very unusual name more obviously associated with immigrant women. The best-known Anne, however, was Anne of Bohemia, Richard’s recently deceased queen. Mindful of the sort of sexual slurs made against Marie Antoinette as part of a political pornographic discourse directed at Louis XVI, I read the Anne of the Rykener narrative, someone’s whore who was herself implicated in the sex trade and who taught Rykener how to have sex as if he were a woman, as a parody of the late queen. As Richard’s companion for a dozen years, Anne died having borne him no children. If Anne the deceased whore parodied the queen, who did Rykener parody?

The name is the clue. Rykener has resonances with Middle English verbs to tell stories, to count or reckon, even to wander about, but if we understand the ‘y’ to sound the same as ‘i’ then the ‘Ryk’ component takes us to Rick, an established diminutive of Richard. (To his friends Richard II was Dick, but this text is not written by his friends.) In this reading Rykener parodies Richard II. It is a parody concealed within the abbreviated Latin minutes of the business of the mayor’s court, an archival accessible only to the court’s officers and clerks. It was the witty confection of these Latin-literate clerks who understood London politics, shared a magisterial perspective on how a city should be governed, and hated Richard with a vengeance. It was a savage wit and it would have cost them their lives had Richard known of it.

Rykener may not appear an obvious parody of the king. Richard is not known for seducing women or having affairs, though keeping mistresses was normal behaviour for a king. His liking for male favourites, however, was well-known. Confronted with de Vere’s skeletal remains after his body was repatriated, he expressed erotically charged feelings. He was thought effeminate because lacking the martial and masculine qualities of his father, the Black Prince or his grandfather, Edward III. Richard pursued peace with France where they had made their names fighting. Richard, moreover, had singularly failed in his duty to father an heir. When Richard later remarried, it was to a bride aged only six. He cultivated an image of youthfulness and was represented in art as beardless, thus reinforcing his reputation for effeminacy. It is this that Rykener parodies. Rykener dresses as a woman, performs women’s work, and has sex with men as if a woman. Medieval understandings of sexuality were not tied to particular orientations – gay, straight etc. – but rather in terms of who did what to whom. The act of penetration was seen as active and masculine, whereas being penetrated was seen as passive and hence feminine. Rykener is effeminate because it is his body that is penetrated and many times over.

We return finally to where the Rykener narrative started. Britby, the horny, but gullible Yorkshireman accosts Rykener on London’s Cheapside wanting sex. Soon after the pair are arrested in flagrante delicto. Out of context, this would be a passing moment in the history of the sex trade: Soper Lane and neighbouring streets, including Popkirtle Lane – the kirtle being a woman’s dress – or the even more matter-of-fact Gropecunt Lane, was a haunt of prostitution despite the city’s official policy of zero tolerance. Seen as political satire this central event carries a very different meaning. Rykener has just returned from a lengthy journey to the west of London, which parodies Richard’s itinerary to York and back when he suspended London’s constitution. Rykener entered the city and made his way to Cheapside, just as Richard was escorted to Cheapside during the ceremonial reconciliation. The climax, which saw Richard crowned by an angel, was what London got for paying a very large cash sum. In the encounter imagined in the Rykener narrative, Rykener is accosted on Cheapside by a man offering money for sex – and remember the previous day London had actually ‘loaned’ Richard another very large sum of money. A few minutes later Rykener is buggered over a stall in Soper Lane. Perhaps the culmination of the satire is wish fulfilment. Having paid their money, Londoners get to imagine Richard being buggered.

Jeremy Goldberg is a social and cultural historian of the English later Middle Ages. He has published widely about gender, family, childhood. His most recent book is Communal Discord, Child Abduction and Rape in the Later Middle Ages (2008). He is currently writing about the relationship between people and buildings as lived spaces. He teaches in the Department of History and the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of York.

Jeremy Goldberg is a social and cultural historian of the English later Middle Ages. He has published widely about gender, family, childhood. His most recent book is Communal Discord, Child Abduction and Rape in the Later Middle Ages (2008). He is currently writing about the relationship between people and buildings as lived spaces. He teaches in the Department of History and the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of York.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com