Kim Racon

On what was likely a cold Sunday night in Cheapside, London, in December 1394, John Britby passed through the high road, catching the eye of a woman called Eleanor. She was bundled up but still held his attention. He approached her and asked her to have sex with him. Eleanor negotiated a price for her labor. Reaching an agreement, they found their way to a stall in Soper’s Lane and had sex. City of London authorities were nearby, waiting, and soon the pair were arrested and imprisoned.

The Mayor and Aldermen of the City, as well as John Britby, learned some time later that Eleanor was also John. And John Rykener now had to answer questions over that illud vitium detestabile, nephandum, et ignominiosum—that “detestable, unmentionable, and ignominious vice,” sodomy.

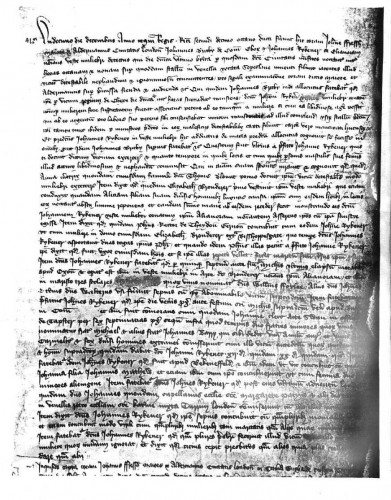

John/Eleanor* Rykener’s confession was that of a male transvestite prostitute in fourteenth-century London, listed in the Plea and Memoranda Roll for the Corporation of London in 1395. When the document was unearthed by Sheila Lindenbaum and edited by David Lorenzo Boyd and Ruth Mazo Karras in 1995, medievalists, especially Carolyn Dinshaw, began many conversations about what Rykener’s confession does to our conceptions and understandings of medieval male sexuality and medieval queerness. Unless more is uncovered about the Rykener case, this confession is as much of the story as we will ever know.

Though brief, it raises many tantalizing possibilities for thinking not just about Rykener’s maleness and heavily coded accounts of male-male sex, but also his convincing, believable, and, at least to some extent, profitable performance of femaleness. Why, in a society that so closely regulated women and often rendered them invisible, would John ever want to be Eleanor? What can Rykener’s Eleanor narrative reveal to us about the potential power behind female performativity in late fourteenth-century London? How does that feminine narrative make us see medieval queer possibilities in light of our postmodern conceptions of, and struggles with, queerness?

Being Eleanor was not just limited to her sex acts; the confession records living and working, both legitimately and illegitimately, as her. The confession also speaks of time spent in Oxford, dressing as a woman, living as a woman, learning embroidery (in addition to sex as a woman, from a prostitute) and working as an embroideress. Eleanor also spent time in Burford as a tapster at the Swan, work not uncommon to medieval women in the late fourteenth-century. Hervarious female tutors taught Eleanor not just how to be a woman, but how to make being a woman most profitable.

Through Eleanor, Rykener shows how effectively women, or operating as a woman, can manipulate and exploit how gender is performed, often to their financial benefit and often at the expense of male clerics. Rykener discusses Eleanor not just having sex with male clerics, but also how much they were willing to compensate her. He seems at pains in his account to highlight the involvement of male clerics in deviant sex, even though these men seemed convinced they were engaging in heteronormative sex with a woman. The original text says he commits the sex act modo muliebri (in a womanish manner) and men have sex with him ut cum mulier (as with a woman), suggesting perhaps intercrural sex. By being active, if perhaps unknowing, participants in male-male sex, however, these clerics disrupt preconceived notions of a perfect, and surely Christ-like, concept of ecclesiastical masculinity, first, through breaking their clerical celibacy, and, second, through their engagement in sodomy (any ‘unnatural’, or non-procreative, sex act). For Rykener, this sex was an integral part of the narrative, and it was sex as a woman that was most profitable and most potentially powerful when answering his interrogation.

Rykener seems versed not only in the power of female sex for personal gain, but also the power of femme couverte de baron, the protection medieval law afforded wives. Trying to steal two gowns from the rector of Theydon Garnon, Rykener even claims to be someone’s wife, threatening a legal suit from her husband to retain the garments. In some ways, then, what medieval authorities would consider Rykener’s deviance also has the potential to highlight kinds of female-specific subversions of social norms.

John/Eleanor Rykener’s sexual activity and gender subversion is just one example, in microcosm, of late fourteenth-century tumult and the possibility to transgress previously held rigid social and cultural boundaries in late medieval society. It’s an example of the medieval not seeming so very static, undifferentiated, and homogenous. In some ways, Rykener’s medieval narrative feels familiar and not so very different from (post)modern narrative struggles between queer selves, communities, and relationships. Passing as Eleanor, but under interrogation unable to strip down to anything other than John, Rykener’s queerness helps show how long the narrative arcs of gender inessentiality and the inadequacy of gender binaries actually are.

* Where she was living and working as a woman, I will describe Eleanor with the female pronoun; when describing his interrogation as John, I will use the male pronoun. The Latin interrogation also employs similar pronoun usage.

Kim Racon is a PhD candidate and adjunct lecturer in the Department of English at Lehigh University. Her dissertation, The goodwyfe had meche to doo: Wives & Work in Late Medieval English Literature, examines the difficulties in articulating and making visible the work of rising merchant class wives. Kim also writes the This Buzz for You column at The Buzz About and tweets from: @raconteursaurus

Kim Racon is a PhD candidate and adjunct lecturer in the Department of English at Lehigh University. Her dissertation, The goodwyfe had meche to doo: Wives & Work in Late Medieval English Literature, examines the difficulties in articulating and making visible the work of rising merchant class wives. Kim also writes the This Buzz for You column at The Buzz About and tweets from: @raconteursaurus

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Reblogged this on Mascara Streaks and commented:

Now this is a fascinating step and look back into history…

Thanks very much! Glad you enjoyed it!

Reblogged this on scaletail.

Pingback: John Rykener Revisited: Transvestite Male Prostitute or Biting Political Satire? | NOTCHES

Pingback: Eleanor or John Rykener | LGBT+ Language and Archives

What an amazing article!

April 1st? Please please please don’t turn out to be an April fools. Because I sooooo want this to be true

I want to believe ️

The impact of the Black Death wiping out between 30-60% of the population was still within living memory at that time, as was the peasant revolt of the 1380’s. With a general acceptance of death being very close, I wonder if many people simply ignored others’ sexuality and just focused on living.

John Rykener plainly made money as a male transvestite prostitute. Many men throughout history have done so, right back to King Solomon and beyond. Why dress him up in postmodern clothes?

‘Rykener’s queerness helps show how long the narrative arcs of gender inessentiality and the inadequacy of gender binaries actually are’

Really? I thought you postmoderns eschewed grand narratives, yet here you are seemingly importing another. Yes, gender is inessential, despite what many transgender activists now argue. But John almost certainly did adopt a gender binary: medieval society would not understand or indeed tolerate sexual ambiguity. It seems very safe to assume that he was John OR he was Eleanor: that’s nothing if not a binary.