Scott Larson

Benjamin Franklin’s dalliances with a cod may not seem particularly notable, given his other exploits. Franklin was an international celebrity in his own lifetime, and for well over a century, scholarly and popular audiences have regarded his Autobiography as the quintessential expression of American ideals. Franklin was also a known womanizer, openly admitted to “intrigues with low women,” fathered at least one illegitimate son, and wrote a cheeky piece of “Advice to a young man on the choice of a mistress.” Yet it is Franklin’s account of breaking his vegetarian diet after being seduced by the smell of frying cod that reveals a great deal about how he encouraged readers to govern bodily desires for food and sex. Even as he joked, Franklin insisted that reasonably managing desires was more useful than dogmatically denying them altogether. Franklin was not simply advocating an early form of sexual liberation; instead he sought to make bodies better instruments for secular civil society, capitalist economies, and republican governments by demonstrating that bodies need not be pure, but well-managed.

Close readings of Franklin’s Autobiography are particularly useful for understanding his vision for public morality, since shaping young Americans was an explicit aim of his text. To justify publishing his memoirs, Franklin quoted friends who insisted that his “little private incidents” would serve as “a sort of key to life” that could teach “business, frugality, and temperance with the American youth,” and might even “bette[r] the whole race of men.” Carefully crafting his tale, the aging printer sought to shape American society by recounting the adventures of a young Ben Franklin, who got into his own scrapes with food and sex.

As Franklin tells the story, in 1723, the seventeen year-old Benjamin ran away from Boston and his indentured servitude to his brother, James. He boarded a ship to Philadelphia under the cover story of having “got a naughty Girl with Child, whose Friends would compel me to marry her,” and while on board, his fellow passengers began frying cod for dinner. Franklin was torn, for he was a vegetarian,

But I had formerly been a great Lover of Fish & when this came hot out of the Frying Pan, it smelled admirably well. I balanc’d some time between Principle & Inclination: till I recollected, that when the Fish were opened, I saw smaller Fish taken out of their Stomachs: Then thought I, if you eat one another, I don’t see why we mayn’t eat you. So I din’d upon Cod very heartily and continu’d to eat with other People, returning only now & then occasionally to a vegetable Diet. So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable Creature, since it enables one to find or make a Reason for every thing one has a mind to do.

His closing quip, that reason quite easily serves inclination rather than principle, fits a larger pattern in his writing: Franklin offers moral prescriptions and then jokes about his failure to live up to them. These jokes are not simple observations about human nature, however; they are rhetorical devices that seek to teach readers that morality is a practice of bodily management rather than an achievement of bodily purity.

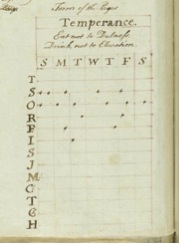

Indeed, Franklin’s famous thirteen-step plan for moral perfection was most notable in its failure, and he “was surpris’d to find myself so much fuller of Faults than I had imagined.” Nevertheless, Franklin insisted that moral management began with eating and drinking:

1.Temperance.

Eat Not to Dullness.

Drink Not to Elevation.

“Temperance first,” Franklin argued, since “it tends to procure that Coolness & Clearness of Head” that could help readers resist powerful temptations. Sexual passions were particularly hard to govern, and temperance helped regulate the “violent natural Inclinations” of sexual desire. Franklin noted that connections between food, drink, and sexuality were strong enough that some writers included “every other Pleasure, Appetite, Inclination, or Passion” in their definitions of temperance. Unlike these writers, Franklin decided to separate sexual from dietary indulgence, and he bookended his virtues with temperance at the top and chastity toward the bottom. This arrangement sandwiched Franklin’s advice for less tangible morals, such as sincerity and justice, between regulations of bodily activities. Notably, diet took precedence over sex as a foundation for moral life, and Franklin’s definition of chastity was remarkably elastic:

12. Chastity.

Rarely use Venery but for Health or Offspring; never to Dullness, Weakness, or the Injury of your own or another’s Peace or Reputation.

Any reasonable creature might find significant latitude in this prescription, and Franklin enjoins chastity not because “venery” was itself sinful, but because its “use” could damage health and reputation.

Like his youthful vegetarianism, Franklin’s thirteen-point moral plan was an exercise in management and reasoning. It did not matter that he failed, but how he failed. Franklin illustrated the difference in the story immediately following his fish-eating tale, in which he lampooned Samuel Keimer, his “piggish” and pious Philadelphia employer. In the story, Keimer, impressed with Franklin’s rhetorical skills, proposed establishing a new religious sect with Franklin, who accepted,

upon Condition of his adopting the Doctrine of using no animal Food. … [Keimer] was usually a great Glutton, and I promis’d myself some Diversion in half-starving him. … I went on pleasantly, but poor Keimer suffer’d grievously, tir’d of the Project, long’d for the Flesh Pots of Egypt, and order’d a roast Pig. He invited me & two Women Friends to dine with him, but … he could not resist the Temptation, and ate it all before we came.

Here, Franklin employed common eighteenth-century stereotypes that portrayed religious difference as a sign of sexual deviance. Religious outsiders like Keimer who claimed to experience supernatural inspiration were derided as “enthusiasts” and considered excessively sensual and bound to highly subjective interpretations of religious injunctions. Franklin’s portrayal of Keimer’s solitary glut suggested that the “enthusiast” indulged in autoerotic behavior, and that masturbation and religious inspiration went hand in hand, a common charge in eighteenth-century satire. Further, by depicting Keimer’s desire for “flesh pots of Egypt,” Franklin drew on Orientalist stereotypes that linked Egypt with decadent foods and sexual excitement. The phrase particularly recalls Exodus 16:3, in which the newly-freed Israelites complained that they would rather eat meat in Egyptian slavery than wander with Moses in the desert. “Fleshpots,” moreover, indicated sexual commerce: Jonathan Swift used the term to refer to brothels that proliferated in London, and increasingly, in Philadelphia. Even though Franklin separated temperance from chastity in his own list of virtues, he mocked Keimer’s religious practices by sexualizing his dietary lusts.

Franklin measured seductions by their outcomes, and he contrasted his reasonable cod-eating with Keimer’s enthusiastic gluttony to illustrate two different modes of bodily discipline. Crucially, Franklin vowed to be social in his eating of flesh—he resolved to eat flesh with others but to return occasionally to a vegetarian diet. This flexibility allowed him to govern his appetites through reason. Keimer’s seduction, on the other hand, was rash and anti-social, and he rudely ate the whole meal before his guests even arrived. A reasonable Creature eats cod with others; an “enthusiast” pigs out alone.

Franklin’s cod piece insisted that bodily desires for food and sex were central features of the ideal American citizen. Neither Franklin nor the Americans he sought to shape were secular ascetics, as Max Weber argued in The Protestant Ethic. Franklin did outline a secular moral program, but his writings aimed to govern inclinations to the benefit of society and industry, rather than to purify a sinful body. Moreover, the body was never ascetic. Franklin’s anecdotes showed how desires for both food and sex were better managed than denied. The Autobiography thus weaves sexual and dietary accommodation into the quintessential account of American character; the “pattern American” ate, drank, and used venery, but did so as a reasonable Creature. By properly managing food and sex, Franklin sought to make the American body an instrument rather than a temple.

Scott Larson is a PhD candidate in American Studies at George Washington University, where his research focuses on gender and sexuality in eighteenth-century American culture. His dissertation, “Enthusiastic Sensations: Religious Revivals, Secular Bodies, and the Making of Modern Sexualities in Early American Culture” is scheduled for completion in Fall 2015, and his work has appeared in the Journal of Early American Studies (Fall 2014). Prior to his PhD, Scott also received a Master of Arts in Religion from Yale University Divinity School. He currently teaches Early American Cultural History at George Washington University. He can be reached by email at smlarson@gmail.com

Scott Larson is a PhD candidate in American Studies at George Washington University, where his research focuses on gender and sexuality in eighteenth-century American culture. His dissertation, “Enthusiastic Sensations: Religious Revivals, Secular Bodies, and the Making of Modern Sexualities in Early American Culture” is scheduled for completion in Fall 2015, and his work has appeared in the Journal of Early American Studies (Fall 2014). Prior to his PhD, Scott also received a Master of Arts in Religion from Yale University Divinity School. He currently teaches Early American Cultural History at George Washington University. He can be reached by email at smlarson@gmail.com

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Very well researched, funny enough, and a lot to be learned.

Thanks