Melanie Huska

This past May, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s announcement of constitutional reforms that would legalize same-sex marriage across the country stirred virulent controversy. This reactivated a debate over “the family” and the jurisdiction of the state that has waged for nearly a century. Heading the attack on the reforms is the National Front for the Family (Frente Nacional por la Familia), an umbrella organization that includes the National Parents Union (UNPF), which was responsible for protesting the introduction of sex education in Mexico at several points in the twentieth century.

Sex education in Mexico shares the broad trajectory of campaigns worldwide: it emerged from eugenics movements in the early twentieth century; was linked to debates over modernity and tradition; was influenced by the global “population problem” in the 1960s and 1970s; and was reactivated by the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s. These shared critical junctures are, in part, the result of the circulation of ideas and dialogue between transnational associations and agencies, such as the early eugenics and feminist congresses. What is unique about Mexico is the way in which debates over sex education were also influenced by the political and economic context of the nation after its 1910 revolution.

The earliest calls for sex education in Mexico emerged in the midst of the country’s bloody revolution, and as such, the debates it generated represented a standoff between the newly emergent revolutionary state and Catholics and conservatives. Hermila Galindo, a prominent feminist between 1915 and 1919, delivered one of the first speeches advocating for sex education. In a speech entitled “Woman in the Future” that she wrote for the opening of Mexico’s First Feminist Congress in January 1916, Galindo argued that women were the sexual and intellectual equals of men and needed to understand the nature of their own sexuality. She called on schools to include the study of the human reproductive system in a required biology course, which she viewed as an antidote to ignorance and religious preoccupations. Galindo represents the confluence of revolutionary-era ideologies, including staunch anti-clericalism, and emerging feminist and eugenics movements.

These ideologies also played a significant role in a 1922 scandal that erupted over the question of sex education. The Governor of Yucatán, Felipe Carrillo Puerto, ignored previous resistance to the introduction of sex education and widely distributed 300,000 copies of a Margaret Sanger pamphlet titled, “Birth control, or the compass of the home.” Sanger linked the need for sex education with the demand for contraceptives and abortions, arguing that women’s ignorance of their sexual functions led to an increased need for both. The pamphlet, about safe and effective “scientific” contraceptive methods, promoted contraception as a component of women’s emancipation and was sponsored by the government of Carrillo and the Socialist Worker’s Party, to which he belonged. Carrillo also invited Sanger to Merida in 1923 to set up birth control clinics. Although Sanger was unable to visit, she sent her associate, and the result was the creation of two birth control clinics in Merida.

Another prominent feminist, Elena Torres Cuéllar, convened a feminist congress in Mexico City in 1923, wherein the Yucatecan feminists spoke out, again, in favor of sex education, birth control, and free love. Though the Yucatecan delegation was the most radical and stole the headlines, proponents of protonatalism and Catholicism at the congress largely rejected or diluted their demands. They dismissed the Yucatecans’ call for access to birth control, for example, citing severe population decline as a result of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Though delegates rejected the use of the term “sexual education,” they did recommend that the school curriculum include biology, hygiene, and prenatal and infant care. As the post-revolutionary government sought to extend its sphere of influence in the 1920s and 1930s, education became a battleground, particularly for Catholics and conservatives who were incensed about the state’s involvement in matters of moral development.

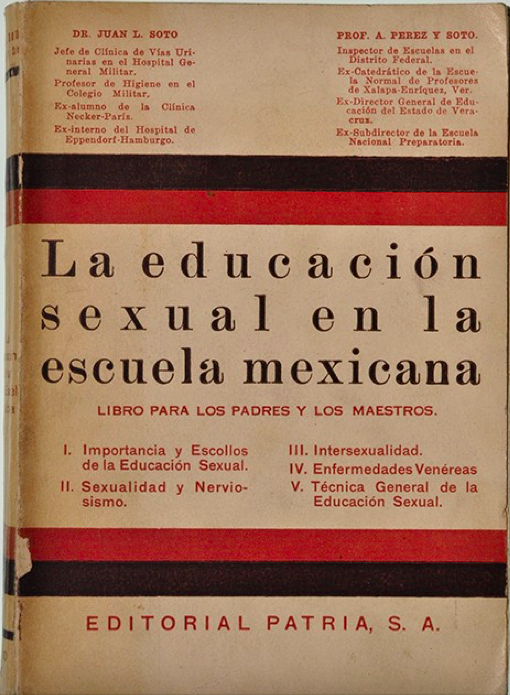

In the early 1930s, Ministry of Public Education (SEP) minister Narcisso Bassols not only promoted co-education, but also convened a committee to consider a proposal from the Mexican Eugenics Society for the introduction of sex education in schools. Catholics, including organizations such as the National Parents Union (Unión Nacional de Padres de Familia), were outraged that the state would intervene in matters they viewed as the realm of the church and the family. The Mexican Eugenics Society’s proposal was supported by a report, collectively penned by well-known physicians, which considered the sexual conduct of adolescents, pregnancy before marriage, venereal disease and sexual perversion, and argued that young people needed the appropriate information that parents were frequently not providing, in part because of religion. The report advocated for trained teachers to introduce sex education curriculum in grades four, five, and six that would teach the elementary facts of life, the dangers of contagious and hereditary diseases – particularly venereal diseases such as syphilis – and the future responsibilities children would face as mothers and fathers.

Even before Bassols released the report to the public, a portion of it was leaked to the national newspaper, Excelsior, who in turn, published fifteen of the Commission’s recommendations. The Excelsior article correctly predicted that the proposal of sex education would generate “virulent” protest. In 1934 sex education was back in the news, when a small group of male secondary school students used a movie theatre as a platform to register their opposition to sex education in public schools, which they argued would corrupt their female classmates. Following their arrest, the boys went on a hunger strike, which in turn, prompted a general school strike and street protests in which twenty parents were injured.

The postrevolutionary government codified their protonatalist approach in 1936 with the nation’s first population law. It emphasized the need to increase the population, particularly in certain regions, borders and frontiers, and to integrate the nation using education and health services. The law placed both a political and cultural significance on larger families and high fertility.

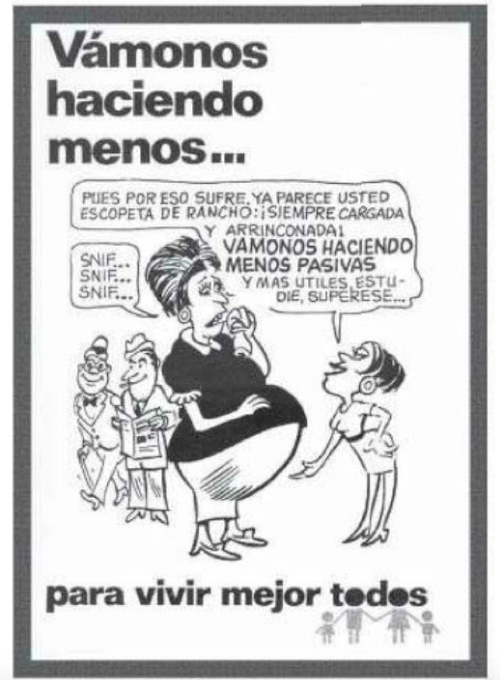

As concern about the global “population problem” circulated in the 1960s and 1970s, Mexico’s official policy of protonationalism started to shift toward an embrace of family planning. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, were permitted to produce and market oral contraceptives, and the first private family planning organization, the Family Wellbeing Association, opened in 1959. It was not until 1973, under the presidency of Luis Echeverría, that the shift was codified into law, which aimed to regulate the population so as to ensure a fair and equitable share of the benefits of social and economic development. The National Population Council (Consejo Nacional de Población México – CONAPO), formed the following year, institutionally linked the ills of poverty, illiteracy, illness, and economic underdevelopment with overpopulation. By the following year, public health agencies advocated the free distribution of birth control pills. The government not only started to promote families with fewer children, but also shifted its approach to parents: instead of supervising or removing negligent parents, it focused on educating them via a media campaign that encompassed radio, television, and billboards with slogans, such as “Let’s Become Fewer” (Vamános Haciendo Menos) and “The Smaller Family Lives Better” (La Pequeña Familia Vive Mejor).

(Vamános Haciendo Menos)

“Let’s Become Fewer…

This is why you suffer. You already look like a ranch shotgun; always loaded and cornered! Let’s become less passive and more useful, study, get ahead.”

Sniff, Sniff, Sniff…

To all live better”

These programs culminated in the National Sexual Education Program (Programa Nacional de Educación Sexual) in 1978, which also employed the media to produce, for instance, short educational films and a radio-novella in order to reach Mexican audiences. Perhaps the most memorable of these projects was the telenovela (soap opera), ‘Acompáñame’ (Accompany Me), which narrated the choices three sisters faced about children and family. The telenovela, drawing together CONAPO, a government family planning agency, and Televisa, the nation’s largest media conglomerate, echoed the message that smaller families lived better. A 23% increase in contraceptive sales, a 500-fold increase in telephone calls about family planning to CONAPO, and the registration of 2,500 women as volunteers for the National Campaign for Family Planning demonstrated the project was a remarkable success.

Several decades later, in 2000, a study conducted by the Mexican Institute for Youth found that both men and women reported that their knowledge of sex education was too basic, more focused on the biology of sex than on relationships. Women, for example, expressed an interest in learning about kissing, orgasms, and masturbation (etc.), not just about prevention. Men in the study echoed this sentiment, noting that their education programs had verbally instructed them in how to put on a condom, but they were not able to practice the technique. Instead, many men turned to magazines or movies to see it carried out. When the SEP expanded and revised the curriculum in 2006, in order to address some of the critiques of the 2000 survey, Catholics, conservatives, and parents groups were once again scandalized and charged that the new material was “pornographic” and “perverse.” Even with the conservative National Action Party (PAN) in power, sex education remained a battlefield for struggle between the state and Catholics over moral jurisdiction.

Melanie Huska is an Instructor in the History Department at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. She received her PhD in History from the University of Minnesota. Her work examines contests in late-20th century Mexico over history and memory in historically themed popular culture, particularly telenovelas and comic books. She is currently working on her book manuscript, Public Histories in Popular Culture: Teaching Mexican History in the Neoliberal Turn. Her second project looks at the history of sex education in Mexico.

Melanie Huska is an Instructor in the History Department at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. She received her PhD in History from the University of Minnesota. Her work examines contests in late-20th century Mexico over history and memory in historically themed popular culture, particularly telenovelas and comic books. She is currently working on her book manuscript, Public Histories in Popular Culture: Teaching Mexican History in the Neoliberal Turn. Her second project looks at the history of sex education in Mexico.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com