Bob Cant

Sometimes a phrase devised for a particular social campaign can be enhanced to signify the wider world view of its instigators. The notion of ‘promoting homosexuality’ gained common currency during the attempts of British parliamentarians in 1987 to outlaw openly discussing homosexuality in lessons in state schools. The legislation best known as Section 28 sought to prevent the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ or the acceptance of homosexuality as a ‘pretended family relationship’. It did not set out to re-criminalise any homosexual activity, but it did seek to hold back any form of learning that suggested that homosexuality was as valid as the heterosexual norm. Second-class citizenship for homosexual people, who were then subject to growing stigmatization on account of the HIV/AIDS crisis, was to be enshrined in law. Active response from LGBT people was swift. Playing with the familiar icon of the London Underground transport system, in 1988 the Never Going Underground campaign inspired tens of thousands of people in London and Manchester to join the UK’s largest ever LGBT rights protests.

Never Going Underground concert with Jimmy Somerville, Manchester, February 1988 (Archives+)

Thirty years later, the phrase ‘promoting homosexuality’ appears again, now used by regimes around the world to indicate their opposition to debates that encourage people to consider how gender and sexuality are socially constructed, that they are not biologically fixed. If the gay liberation movement of the 1970s seemed to propose a revolutionary transformation of the ways homosexual people saw themselves, then the very notion of ‘promoting homosexuality’ can be seen as a warning from the forces of a counter revolution: nothing must be allowed to challenge the belief that there is a fixity about sexuality and gender. The phrase is very strongly resonant of the 1980s when, as the Pet Shop Boys declared, ‘everything was for sale’. It represents not so much an intellectual response to the process of questioning the social construction of sexuality as an invitation to succumb to a particular form of promotional advertising.

The ethos of 2017 is very different from that of 1987, but the ‘brand’ has been successful and continues to be used by its proponents as a slogan of a worldwide anti-emancipatory sexual politics. Russia has been particularly prominent in advocating the need to protect the young from anything which promotes ‘non-traditional sexual relations’ and organisations. The country’s only helpline dedicated to offering counselling and support to LGBT people was closed down following the introduction of legislation in 2013. It is more difficult to clarify the links between the legislation and the torture and murder of gay men in Chechnya, but the climate created by the law does make it easier for the regime there to act with impunity. Uganda’s 2014 Anti-Homosexuality Act also criminalises anyone who promotes or abets homosexuality and punishment can be as much as five to seven years of imprisonment. The Act is subject to legal appeals but, once again, the climate of homophobia is permitted and community events such as Pride celebrations are subject to threats and enforced cancellations. As Frank Mugisha said: ‘Our community is traumatised by the arrests and detentions.’ Brazil has not yet introduced any such legislation but earlier this year the gender theorist Judith Butler was described as a witch and burned in effigy on the grounds that her theories could lead to children choosing to change their gender. The wilful opposition to learning about the development of gender and sexuality such as we experienced in the 1980s remains all too widespread and vicious today.

While there has been widespread international opposition to increasing state-sponsored homophobia, very often it seems to be based on rather defensive, and potentially misleading, terms. Lady Gaga’s popular song “Born This Way” has been seen as supportive of the right of people to be Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender (LGBT) on the grounds that these are biologically determined. It does feel as though one notion of fixity is being counterposed with another. The anthropological, cultural and historical knowledge that we can have about the different ways in which gender and sexuality can develop in different circumstances is being overlooked and priority is being given to an assertion of medical certainty both by LGBT people and our allies, as well as those who would condemn us. Similar medical arguments were used in the UK in campaigns in the 1960s to de-criminalise male homosexual activities, but tactics that were appropriate to a particular campaign then may not be the most effective way of organizing resistance today.

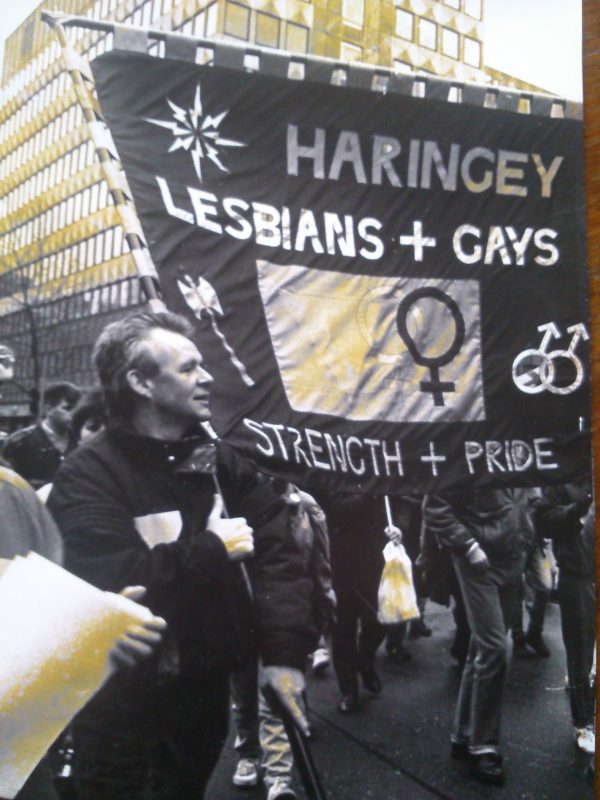

In recent years there has been growing interest in the concept of intersectionality and the way it offers insights into the connections between different social categorisations and the inter-dependence of different forms of discrimination related to racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, class and other forms of belief-based bigotry. Recognising intersectionality isn’t new. Even if we did not have the term in 1986, the same sentiment animated our anti-racist and anti-homophobic action in Haringey, London immediately preceding Section 28. These can be difficult concepts to engage with and, although there is growing interest in intersectionality in academic circles, it can hardly be described as the word on the street. There needs to be a way to popularise the notion that the development of gender and sexuality is part of a complex process, which goes beyond historically inaccurate notions of an eternal fixity.

We need to think creatively about intersectionality, inspired by the ways in which activists before us have built wider awareness. In the 1970s, the image of a pink triangle, which had been used by the Nazis to identify homosexuals, was reclaimed to become the iconic symbol of the pride being generated by the burgeoning gay movement. ACTUP succeeded in disseminating its message during the HIV/AIDS crisis through the adoption in 1987 of the powerfully direct slogan SILENCE = DEATH. The Wobblies’ song “Bread and Roses” is still used as an anthem of working-class solidarity in the way it was in Pride, the film about the solidarity shown by Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) to striking miners. It will not be important whether we use a slogan or a badge or a song; what is important is that we find a pithy way to disrupt complacency and convey the complexities of sexuality and gender identity.

Read more about Section 28 at NOTCHES

Thatcher and Homosexuality: Waiting for Section 28 Bob Cant discusses how, even before the introduction of Section 28 on 7th December 1987, there had already been a rising tide of hostility, from a variety of sources, to the development of policies which allowed children and young people to learn about the development of sexuality.

The Road to Section 28 Colin Clew explores the twists and turns in the Labour Party, as it sought to come to terms with a policy with which some of its members felt very uncomfortable.

Sexual Politics in the Era of Thatcher and Reagan Jeffrey Weeks’ 1988 interview with Marc Stein examines the impact of Section 28 on groups in society and commented on the fact that Section 28 had succeeded in generating, against the odds, a tremendous mobilisation of common purpose among lesbians and gay men.

Challenging Heterosexism: The Haringey Experiment, 1986-1987 Bob Cant explores an earlier unsuccessful attempt to understand such inter-connections in the London Borough of Haringey in the run up to Section 28.

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

Bob Cant has been a teacher, a trade unionist, a community development worker, a Haringey activist and an editor of several collections of LGBT oral history. He now lives in Brighton and his first novel, Something Chronic, was published in 2013. Bob tweets from @bobchronic

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Fantastic read. Thanks. Bw. David