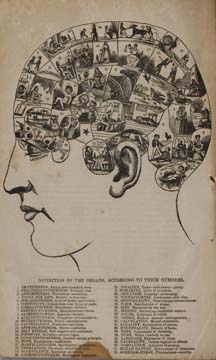

Nineteenth-century medical texts are extremely diverse in the topics they cover. They range from specialized works meant to be used by trained physicians and surgeons, to books of practical home remedies, to treatises on phrenology. They also offer much more than strictly medical advice – many of the works contain recommendations on how to navigate the complicated waters of love and marriage.

Not surprisingly, one theme that appears in their writings is how to reconcile the tension between physical attraction – necessary for procreation – and the loftier spiritual love which would bring two people together in marriage. Orson Squire Fowler, who along with his brother Lorenzo, was one of the leading proponents of phrenology during the nineteenth century, had plenty to say about love and sexuality. His fundamental belief was that love existed to drive procreation:

What inspires and enables gender to create offspring; and those precisely like their parents? LOVE. Only for this was it created. To this alone is it adapted.

And as such, it should only exist within the bounds of marriage. George Napheys, a physician practicing in Philadelphia, held a similar view. He said that,

the passion of love is dependent upon the capacity of having offspring, and that such was the intention of Nature in implanting in our bosom this all-powerful sentiment.

So, love is a good and wonderful thing because it is the great force that allows the human race to survive.

The question of how much physical pleasure should be gotten from the marvelous force of love could, however, be a somewhat sticky question. When nineteenth-century physicians and quacks mentioned the physical aspects of love and attraction, it was usually in the context of propagation. Fowler, who won notoriety for writing more openly about sexuality than many of his contemporaries, still defined it in the context of marriage. Fowler, on unmarried women:

Let her who has no husband to love, or with whom to share her lot, dress gayly, sing sweetly, do and be whatever she pleases, no life-pleasures really count unless shared with the one she loves).

In turn Napheys, while acknowledging that sexuality was a positive force, also added the caveat that this was mainly the case due to its role in creating children:

It is a false notion, and contrary to nature, that this passion in a woman is a derogation to her sex….It is a natural and healthful impulse…The feeling which excites to the preservation of the species is as proper as that which induces the preservation of the individual.

John Harvey Kellogg, physician and cereal maker extraordinaire, was opposed to excessive sexuality. He believed that marriage did not allow young couples to “indulge the passions;” instead, “martial excesses” resulted in a dangerous decline of health, and that sexual relations should only occur when the couple was trying to conceive children. Kellogg believed men were the primary instigators of carnality for its own sake – the fact that women might be interested in initiating sex for pleasure with their husbands didn’t seem to cross his mind.

It’s easy to look at nineteenth-century texts and think of them as archaic, but echoes of their positions can still be heard today. Today’s society might not put as much emphasis on marriage as the only proper venue for love, but it is still concerned with the distinction between love and lust, and if what the advantages and disadvantages of casual sex are. While the nineteenth-century idea that sex and love can only properly be found in marriage no longer holds as much sway as it once did (although that also depends on which segment of society you’re looking at), the same issues they addressed in their archaic, somewhat amusing prose are still being debated today.

Elisabeth Brander is a rare book librarian at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Bernard Becker Medical Library. She is also a student of the history of medicine, and a writer of tales. Elisabeth has a particular interest in anything that is strange and macabre. She tweets from @E_Brander.

Elisabeth Brander is a rare book librarian at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Bernard Becker Medical Library. She is also a student of the history of medicine, and a writer of tales. Elisabeth has a particular interest in anything that is strange and macabre. She tweets from @E_Brander.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

It certainly always bears repeating that ‘Victorian’ ideas about sexuality and conjugal relations were very far from monolithic, but I find it useful, when talking about ‘the nineteenth century’, to locate these discussions geographically as well, since there were significant national/regional differences in sexual cultures. The authors you discuss were all US-based, although their works were distributed in the UK (not sure about other countries/languages). I’m also a bit dubious about assimilating a number of different discourses about health, healing, etc, under the heading ‘Nineteenth century medical texts’ when they were, especially when talking about books aimed at a popular audience, coming from alternative or fringe systems, which might well have been consciously counter to the orthodox medical mainstream. E.g. the works of Mary Gove and Thomas Nichols, such as Esoteric Anthropology, based on the hydropathic system: also very much about sex for procreation only. (I discussed some of these issues in the UK context in the ‘Victorian Polyphony’ chapter of The Facts of Life.)

Thank you so much for taking the time to comment – you’ve brought up some very good points for me to consider moving forward. I appreciate it!