Beardedness, or alternatively clean-shavenness, has long been an important signifier of manliness, inscribing crucial gender and sexual meanings onto the male body. But fashions in shaving are notoriously unstable, even in the nineteenth century, that idyll for the hirsute among us. Beardedness in nineteenth-century Britain, in fact, only reached its zenith in 1892, while the frequency of clean-shaven faces, lowest in 1886, continued to increase in popularity for the next 80 years. The necessity and expense of daily visits to the local barber, however, prohibited many from indulging in such luxury and before savvy marketers rooted the fear of the five o’clock shadow into men’s minds, a few days’ growth was often acceptable. Indeed, before the advent of the safety razor, many men might have agreed with the proverb: “It is easier to bear a child once a year than to shave every day.” Beardedness, and its intermediate variations, nonetheless had (and continue to have) definite implications for manliness and sexuality.

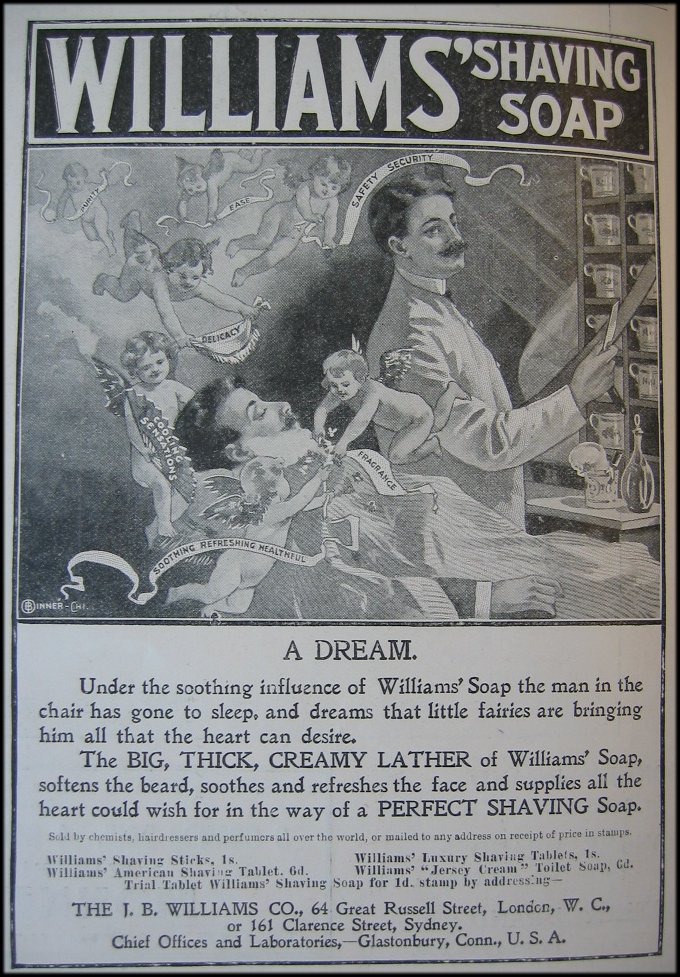

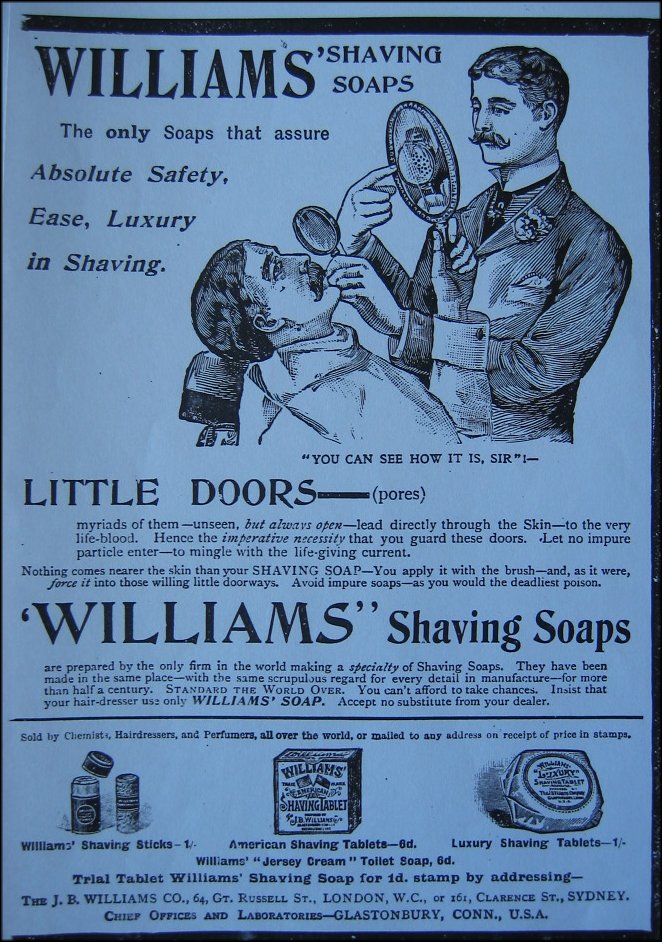

A period of gender and social instability, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also saw the valourization of particular forms of masculinity, reinforcing in men a sense of strength and virility to counter perceived emasculation. This is exemplified in ads displaying, oddly enough, domination through the act of shaving. Purporting only to refer to pores, an 1899 Illustrated London News ad entitled “Little Doors”, for example, evokes sexual penetration. When applying shaving soap to one’s face, the ad instructs men:

you apply it with the brush – and, as it were, force it into those willing little doorways (emphasis in original).

Masculinity here is represented in complex ways. The man in the ad is the active agent while his pores remain passive and docile. While pores are in fact part of the man’s own body, they can only be perceived through the double lens of magnifying glass and mirror. They are almost independent agents against which he must rally. Men are told to “force it” into pores, described as “willing little doorways.” The ads textual representation of masculinity is aggressive, even if the pictured man lies semi-supine submitting to his barber’s directions.

The barber with magnifying glass and mirror (described by Anne McClintock as a fetish object of enlightenment and self awareness) shows his customer the many “Little Doors” or pores of his face. There are, worryingly,

myriads of them – unseen, but always open – [that] lead directly through the Skin – to the very life-blood. … Let no impure particle enter – to mingle with the life-giving current (emphasis in original).

These “Little Doors” are the sites through which a man can be violated, his “life-giving current” poisoned. By their very existence these pores indicate the vulnerability of the male body; they remain “always open,” a portal through which impurity can enter. Hence the “imperative necessity,” as the ad warned, “that you guard these doors.”

As liminal borders marking uncertainty and potential dangers, the cultural currency of doors at this time is also clear in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) in which the first chapter is titled “The Story of the Door.” Marked by a “prolonged and sordid negligence,” the door is “blistered and distained.” It is through this back door that Hyde, embodiment of vice, enters the house. Sexual and anal vulnerability are one available reading. Similarly, in the “Little Doors” ad, men are exhorted to master their “little doorways,” or pores, and eliminate the threat of vulnerability they represent. They are reminded that these “doors” are “willing” agents, complicit in the potential corruption of the body. They must avoid impurities as they “would the deadliest poison.” It was imperative that men adopt the attributes of normalized masculinity: bodily and sexual self-control and self-discipline.

In an era before manufacturers offered three (even four! or five!!) blades on springs protected by fine wires and augmented by microfins and moisturizing strips, shaving posed a genuine threat of bodily injury. As understandings of microbial life and the dangers of infection developed, Nancy Tomes argues that a preoccupation with hygiene, what she calls The Gospel of Germs, took hold of individuals at this time. Men began to shave their beards and women to raise their skirts to avoid the danger of carrying infection. In hospitals too, patients were made aseptic through scrubbing and shaving, while doctors followed by sacrificing beards and moustaches “on the altar of asepsis.” The anti-TB movement also made inroads against facial hair. The luxurious beard was now to be sacrificed to “spare loved ones the curse of hairy, germ-laden kisses.” One anti-TB slogan asked men to “Sacrifice Whiskers and Save Children.”

It is noteworthy that men in this and similar shaving product ads often share a remarkable resemblance to their barbers, one face representing both subject and object in the act of shaving. Fin-de-siècle consumers encountered confusion in the images of masculinity in such ads. But even before the beard became unfashionable, aesthetes like the appropriately named Aubrey Beardsley and also Oscar Wilde deliberately sported a smooth face to express their antipathy for stifling middle-class values and expectations. Their own sexual ambiguity was reflected in their sartorial and personal grooming choices. Already in the late nineteenth century, beardedness and clean-shavennness were never easy-to-read markers of masculinity or sexuality.

Justin Bengry is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London and a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in History at McGill University, Canada. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Queer Profits in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

Justin Bengry is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London and a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in History at McGill University, Canada. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Queer Profits in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Pingback: Shaving and Masculinity in the Gilded Age - Lawyers, Guns & Money : Lawyers, Guns & Money

Reading a bit too much into it, no?

I’m happy to have readers carefully examine the sources and engage with my understanding of them, dispute my findings, or offer alternatives. But, no matter how we might read them differently, I think that ads’ word choice and imagery (here or in others) all have something valuable to say about understandings of gender, the body, social change etc. when they were produced, and can enlighten us as to what issues and concerns held cultural currency and resonance for their creators and consumers.

Pingback: Sunday Morning Medicine | Nursing Clio

Pingback: Hirsute Phoenix: Conchita Wurst, Beards, and the Politics of Sexuality | Notches: (re)marks on the history of sexuality