The manifesto of Monokini 2.0, a social art project centred on swimwear designed for women who have had a mastectomy, advocates,

We think that the current focus on a breast-reconstruction after mastectomy as the only way to a full life, is a breast-fixated way of seeing what a woman is…We want to incite a positive self-image of breast-operated women by showing that you can be whole, beautiful and sexy even with just one breast or with no breasts at all. (Monokini 2.0)

Breasts are fundamental to our collective understanding of female sexuality. This association has profound implications for the way cancer of the breast is perceived, responded to and dealt with by the media, the public and by medical professionals. This “breast-fixated way of seeing what a woman is” has resulted in the sexualisation of breast cancer awareness campaigns that reflect the old adage that sex sells. The Save the Ta-Tas campaign in the United States produces t-shirts that proclaim, “caught you lookin’ at my ta-tas” and “I love my big ta-tas.” Toronto’s annual Boobyball party to benefit the charity Rethink Breast Cancer produced a public service announcement that insisted, “You know you like them/now it’s time to save the boobs.” The message is clear: breast cancer is worth paying attention to because the disease and its treatment reduce women’s desirability and prevent male access to the female body. Viral video campaigns may be unique to our own age, but the feminine and sexual context of breast cancer care, treatment and culture is not new.

Breast cancer awareness campaigns were not a feature of nineteenth-century Britain. However, this period saw a clarification of the idea that breasts and breast cancer were biologically linked to a woman’s femininity and sexuality. Some physicians therefore looked towards those physical embodiments of femaleness – the ovaries – for an explanation for breast cancer’s cause and progress. George Beatson, a surgeon in Glasgow, selected a young woman with inoperable breast cancer. He removed both of her ovaries and within weeks her tumors shrank. Six months later she seemed free of disease. Beatson reported his findings in 1896 and started regularly performing the procedure on patients. The practice of removing the ovaries was not universal. Nonetheless, almost every leading specialist made the connection between breast cancer and the woman’s reproductive organs. Dr. D. Hayes Agnew said, “The sympathy that exists between the ovary, the uterus, and the mammae has a pathological as well as a physiological importance.” Physician Charles H. Moore insisted that “a connection between the genital and the mammary disease [was a] connection of cause and effect.” The bio-medically reinforced link between a reductive conception of femaleness and cancer of the breast had profound ramifications for clinical interpretations of cancer.

Sangeeta Mediratta’s work on Frances Burney’s 1811 account of her own mastectomy reveals that the removal cut to the very heart of her “feminine identity” as defined by early nineteenth-century culture. Burney’s account includes a note from her husband that insists despite the loss of her breast she is no less a woman, rather she is “more than half Angel” with “sublime courage.” She also writes: “M. Moreau [the surgeon] asks if I had cried or screamed at the birth of Alexander and I said that it had not been possible to do otherwise.” An interception of maternal memory just as her mastectomy removes the physical sign of her motherhood, reminds the reader that she is a woman.

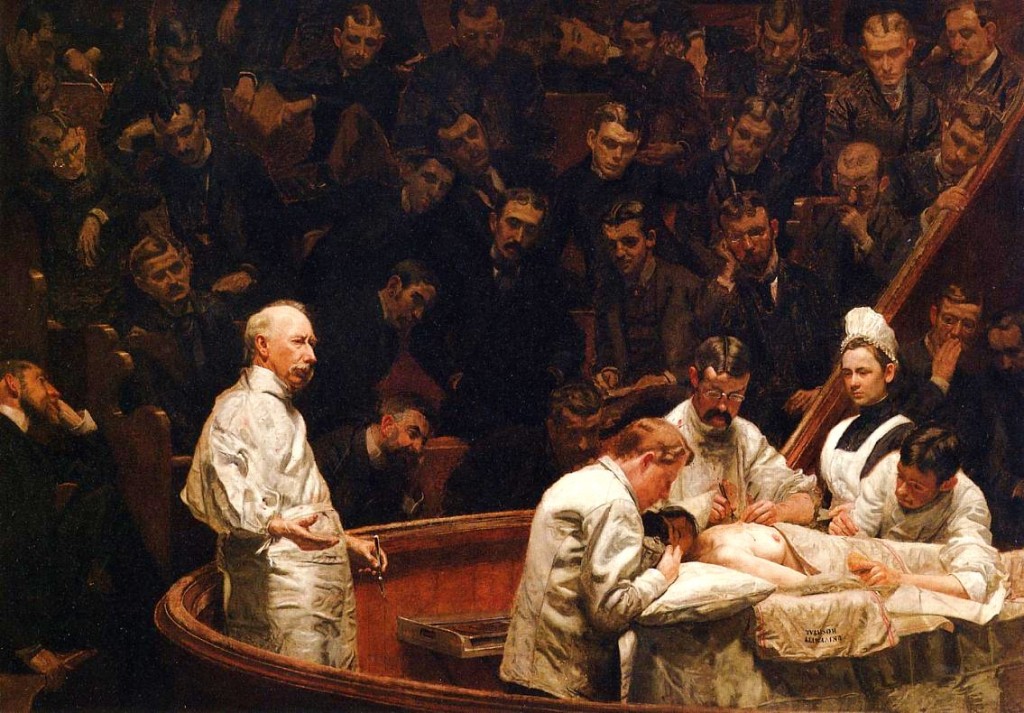

Breasts were not only representative of femaleness because of their associations with reproduction; they were highly sexualised body parts. This posed a significant challenge to nineteenth-century doctors who were tied up with ideas about modesty and female purity. During surgery the healthy breast was to remain concealed. Nurse Clymer, assistant to Dr Agnew, wrote these instructions in her class notes: “For a breast cancer case only put one arm in the night dress, be sure to have the one exposed that is to be operated on.” Dr Agnew called for a light blanket to cover the healthy breast during the operation. However, this conflict between the sexualisation of breasts and surgeon’s sense of propriety can be traced in the erotic tensions of many nineteenth-century visual representations of breast cancer and its treatment.

The Agnew Clinic [Figure 1] was commissioned to celebrate the retiring Professor of Surgery, Dr. Agnew. The display of the patient’s healthy breast – in contrast to the recorded procedure – suggests a voyeuristic element to the painting. In addition, the patient’s breast is youthful when breast cancer usually affects post-menopausal women. In Henri Gervex’s Before the Operation [Figure 2], which depicts a patient being prepared for a mastectomy, the patient’s supposedly cancerous breasts are youthful and show no signs of disease. Both breasts are exposed; her hair flows loose across her pillow. While twenty-first century awareness campaigns may be more explicit in their efforts to garner support, they draw on a long-term sexualisation of breasts and a deeply ingrained association between femininity and the intact breast.

No doubt many women, both past and present, experience breast cancer as an assault on their femininity. This is where the Monokini 2.0 project is so powerful – it attempts to correct the narrative that suggests women are only feminine and only sexual with their breasts unblemished or reconstructed. However, it also places itself at an interesting juncture. In decrying the “breast-fixated way of seeing what a woman is” and demanding that people confront and see beauty in the damage done by the disease, it follows a problematic and long-standing feature of breast cancer discourse: that sexuality is the feature of womanhood most in need of protection.

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a PhD Candidate at King’s College London, researching the history of breast cancer in nineteenth-century Britain and the US. She is broadly interested in issues of gender, sexuality and race, as well as NHS reform and global health. She works for a small women’s health charity that advocates for sexual & reproductive rights in sub-Saharan Africa. She tweets from @agnesjuliet.

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a PhD Candidate at King’s College London, researching the history of breast cancer in nineteenth-century Britain and the US. She is broadly interested in issues of gender, sexuality and race, as well as NHS reform and global health. She works for a small women’s health charity that advocates for sexual & reproductive rights in sub-Saharan Africa. She tweets from @agnesjuliet.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Fascinating history. Interesting observation that both of the women in these paintings are young and nubile, not the more common post menopausal breast cancer sufferers. It strikes me that choice of a young woman as the subject in these mastectomy paintings also connects with the trope of the dead or dying girl in 19thC art and fiction. But now two tropes of 19thC art come together — the dead or dying girl (the passive object of male desire) who despite death and disease is glowing white with flowing hair, but here meets the Mastery of Masculine Science! Modernity and technology step in to intervene and bargain with Death and Decay. I think here there’s an ambivalence to the juxtaposition, especially the Gervez… –Getting carried away here with my reading. Great stuff to work with!