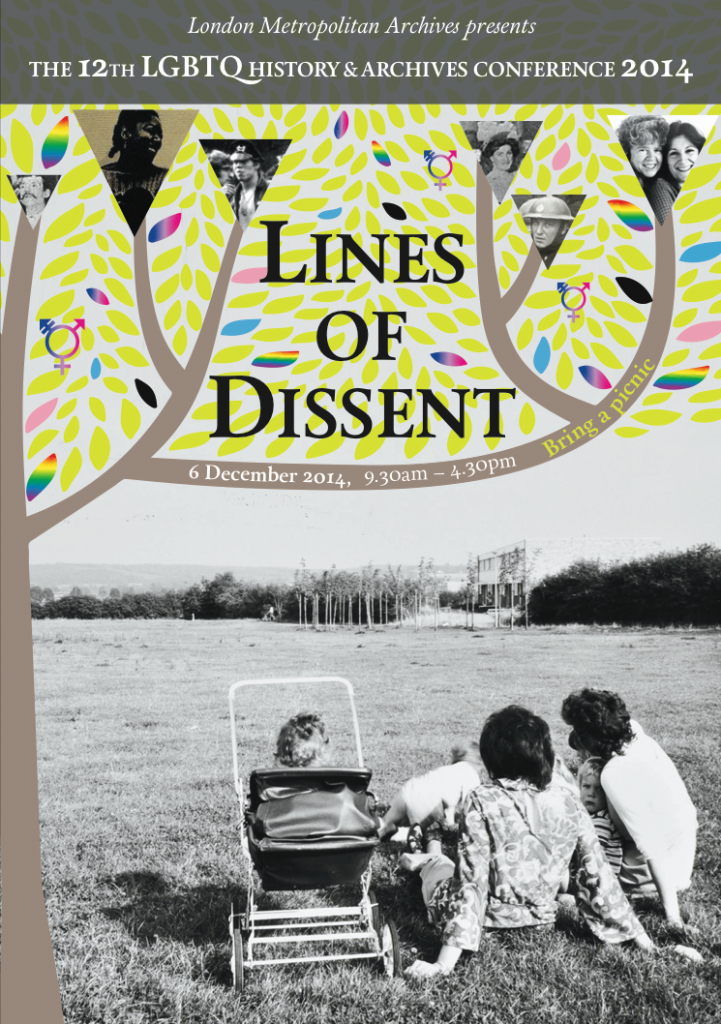

On Saturday 6 December, historians, archivists and activists joined together at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) to discuss ‘Lines of Dissent’. The 12th LGBTQ History and Archives Conference at LMA chose queer inheritance as its theme this year, which was run in collaboration with the Raphael Samuel History Centre (RSHC). (Disclaimer: NOTCHES is sponsored by RSHC, and I am also a team member). The annual conference raised questions about recording and reading queer inheritances and highlighting ways that queer history and individuals subvert traditional lines of heritage.

The day began with a keynote by Daniel Monk, Reader in Law and Director of Birkbeck Gender and Sexuality (BiGS), who discussed the perils and pleasures of queer wills. Monk placed queer history within the history of inheritance, highlighting the ways in which queer wills differ from ‘straight’ wills. For example, queer wills include more instances of friends as beneficiaries, as well as more godchildren, nieces and nephews (and the ‘lesbian clause’ — cats). Monk also argued that while queer wills provide an insight into who queer people have gifted to, they are also significant in who is excluded from wills. Monk posited that wills are also a way for queer people to communicate with family members who have rejected them for their sexuality, omitting them and subverting lines of inheritance through gifts to non-family members. Mixing together money, death, families and friendship with queer history make for a fascinating reading, and in doing so Monk highlighted the importance of the many ways we can interpret and subvert inheritance to reveal LGBTQ histories.

The conference took a more creative approach throughout the rest of the day, with delegates joining a series of workshops. The morning workshops were facilitated by Justin Bengry and Amy Tooth-Murphy, and saw delegates piecing together the image of a person from their ‘archive’. Delegates were provided with boxes of memories — objects that might document a queer life — and encouraged to think about who this person might be, what they did, whom they loved and how they lived. It’s a task I’m used to as a historian, but as my research focuses on representations of queer history, I’m used to doing this the other way around, already knowing the name, life and significance of the subject before working through objects or related documents. Piecing together the significance of objects in the workshops gave a refreshing look at how we construct histories, and the way can project our own experiences and opinions onto the past.

The afternoon saw a different set of workshops on ‘Presenting evidence of LGBTQ lives: breaking and making history’. Three of these were carousel workshops, while Rudy Loewe’s ‘Here We Are: Visible QTIPOC Histories’ continued throughout the afternoon. I attended Sean Curran’s ‘Queer Homes, Queer Houses’, where we heard about their PhD research on queer interpretations and interventions of historic houses, and went on to create ‘museums of ourselves’. The workshop asked delegates to ‘think creatively about the traces their identities leave on their homes’, and the result was a group piece of artwork that showed our past homes and the memories they contained. Sean has created a vlog of the final product, which you can view on their blog.

My own research also focuses on queer historic houses, and I enjoyed taking a more creative approach to the same subject. This also highlights one of the most successful aspects of the annual LGBTQ History and Archives conference that I don’t often see at other conferences: a creative element that comes from delegates with a wide range of backgrounds and interests in queer history.

The final workshop I attended was ‘Finding the stories of “female husbands”’ with Caroline Derry. Using the case of Ann Marrow, we discussed the difficulties of using court records to explore the history of ‘female husbands’, biological women who lived as as men and married other women. This session raised significant questions about interpreting the historical record, particularly for LGBTQ histories. For example we’ll never know whether Ann Marrow was in loving relationships with the women they married, or indeed whether their wives were aware of their sex, so how do we interpret this as queer history?

Marrow’s records and the workshop discussions throughout the day heightened the importance of tracing ‘lines of dissent’ in the archive, which, although often raising more questions, go a significant way to revealing the complexity of LGBTQ histories. While the next LGBTQ History and Archives conference is a year away, LMA holds a monthly LGBT History Club, which continues the work of finding lines of dissent in the archives throughout the year.

Claire Hayward is a PhD candidate at Kingston University, where she researches representations of same-sex sexuality in public history. Her other research interests are in the history and politics of sexual identity, and sexuality and gender in the eighteenth century. Claire blogs at Exploring Same-sex Sexualities in Public History and is co-editor of History@Kingston. You can follow her on Twitter: @HaywardCL

Claire Hayward is a PhD candidate at Kingston University, where she researches representations of same-sex sexuality in public history. Her other research interests are in the history and politics of sexual identity, and sexuality and gender in the eighteenth century. Claire blogs at Exploring Same-sex Sexualities in Public History and is co-editor of History@Kingston. You can follow her on Twitter: @HaywardCL

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com