It is no exaggeration to say that this year one could attend the annual meeting of the American Historical Association (AHA), held in early January in New York City, and experience a queer conference within a conference. The US Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender History brought seventeen panels to the AHA’s annual program, seven of them officially designated as joint panels with the AHA. Three of those joint-listed panels concerned the practices of sexology, presented under the umbrella title, ‘Toward a Global History of Sexual Science, c.1900-70’. Organized by Doug Haynes and Veronika Fuechtner at Dartmouth College and Ryan Jones at the State University of New York, Geneseo, the nine papers presented on the three panels grew out of a Humanities Institute workshop held at Dartmouth in the Summer of 2013, devoted to a consideration of sexual science as a global phenomenon. Many of those papers will eventually appear in an edited volume; when they do our understanding of sexology will be immeasurably richer.

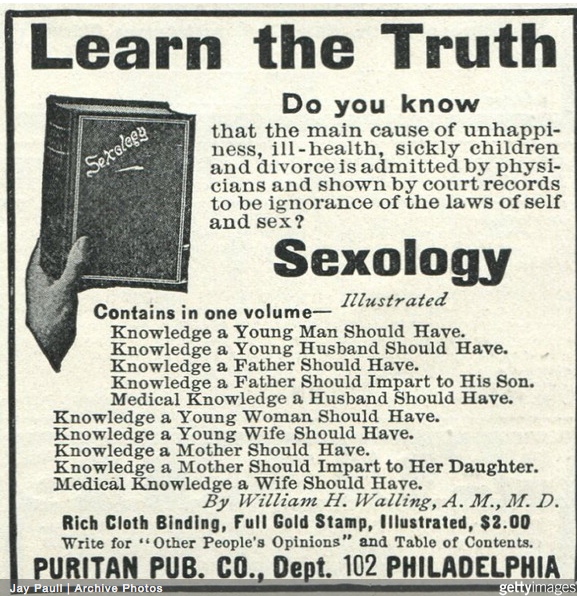

Only recently have we begun to explore the varied global dimensions of sexual science. All too often we have focused on the ideas of specific thinkers we lump together as sexologists, albeit largely within the context of their own, limited national cultures in the West – and through the practices of a narrow intellectual history. To be sure, we now have excellent studies of the writings of a number of important western sexologists, including Otto Weininger (by Chandak Sengoopta), Richard von Krafft-Ebing (by Harry Oosterhuis) and, now, Magnus Hirschfeld (by Elena Mancini). Furthermore, we have works that trace the ‘influence’ of ideas in the realm of sexology across national borders, albeit still largely within Europe and North America: we can read about the circulation of psychoanalytic ideas in Central Europe and beyond in the first half of the last century, and, in addition, can study just how influential the ideas of other sexologists were on Freud’s 1905 essays on the theory of sexuality. That said, ideas have more often than not been traced in isolation from their broader effects. Moreover, the mere tracking of ‘influence’ is always a bit of a dubious proposition, given that when we set out looking for connections we often find exactly what we are looking for, creating specific intellectual genealogies that might tell us more about the thought processes of those who concoct them than those who are being written about. But, most of all, the intellectual practices we have brought to bear on the study of sexology have, with a few notable exceptions, seldom been applied, let alone interrogated and expanded, beyond a comfortable focus on the West. Many of us who work on the history of sexuality have heard of Havelock Ellis, and of the other so-called ‘founders’ of modern sexual science, but not of R. D. Karve (India), or Alejandro Lipschutz (Chile), or Benjamin Argüelles and Alfonso Quiroz (Mexico), or Pan Guangdan (China), to name just a few of the large cast of characters who populate the papers read in New York.

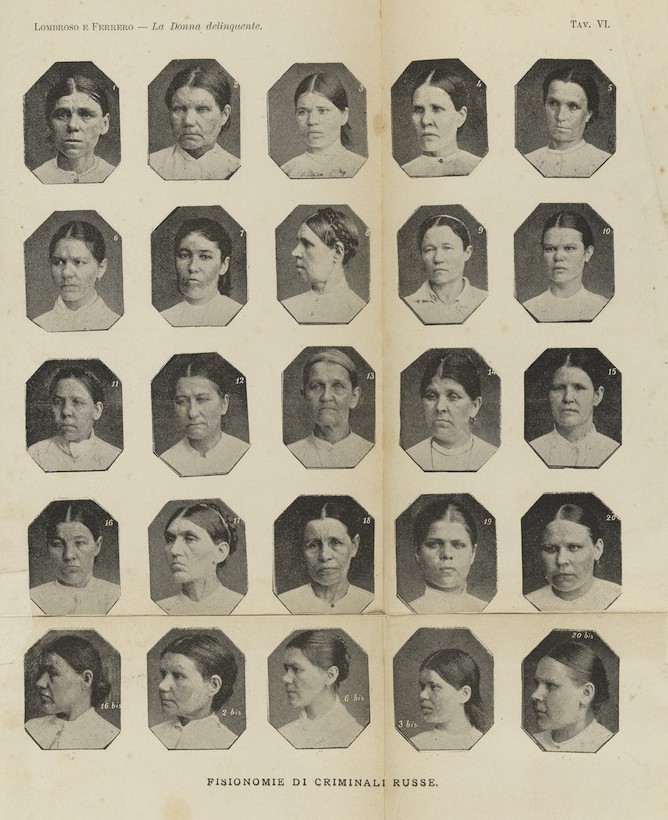

If ‘influence’ often suggests a one-way process in the transmission of knowledge, so too do the standard models of ‘westernization’ and ‘modernization’, models that are either ignored or wholly rejected in this new work on the global history of sexology. The papers presented in New York are not built around notions of the triumph of a western science of sex. Rather, they rehistoricize the thinkers we think we know in both local and global contexts and bring to light new thinkers who have not been the subject of enquiry before, a whole cast of characters who both refashioned the ideas of the classic western thinkers and advanced new ideas of their own. Furthermore, taken together the nine papers speak less of influence than of reciprocity, less of a one-way journey than of the ‘multi-directionality of intellectual exchange’, to borrow from the title of one of the panels. Focusing on the circulation of knowledge, the papers also examine the various ways in which ideas were both appropriated and reconfigured – how sexological works with which we are familiar were transformed through processes of translation, hybridization, and transculturation. Chiara Beccalossi, for example, focuses on a series of increasingly important transnational networks of exchange through which Cesare Lombroso’s criminal anthropology and Nicola Pende’s biotypology circulated and were appropriated – and given new meaning – outside of Italy, in very different national contexts, especially in Argentina. Likewise, Ryan Jones dissects the eclecticism that characterizes Mexican writing about homosexuality, focusing not merely on what was borrowed from western sexologists, but on the ways in which much of that work was rewritten and refashioned, creating a distinctive, indigenous product that subsequently circulated elsewhere in Latin America. Emphasizing that Mexican sexologists ‘were ideological and methodological polyglots’, Jones reminds us of the importance of studying the promiscuous intermingling of ideas in the field of sexology.

Important, too, in all the papers read on the three global sexology panels at the AHA, is the careful attention paid to the specific socio-political contexts in which sexological ideas took root – the context in which they were received, through which they were filtered and rendered intelligible. Kurt MacMillan, for example, carefully reconstructs the creation of what he terms a new ‘Hispanic network of sexual science’, rooted in the needs of Latin American societies but revealing connections spread over a porous geography of scientific disciplines, international conferences, nation-building projects, and racial ideologies that cut back and forth across Chile, Spain, and central Europe. Likewise, by offering a careful analysis of the various translations of the work of Havelock Ellis in Republican China (1911-49) – and by noting what was translated and what was ignored – Rachel Hui-Chi Hsu explores how various figures in China attempted to reconcile the ideas of Ellis with traditional Chinese culture and extract certain elements of his thought to propose solutions to China-specific problems.

Most promising about much of this work is that it moves not only beyond a narrow focus on ‘influence’ but that it also attempts to write a global history of sexual science as something more than an isolated intellectual project. Ideas matter, and they have effects, and we need to pay close attention to the projects of the modern nation state and to the ways in which those projects are often bolstered by specific work in the human sciences, which are called upon to assist in their legitimation and implementation. This, too, is a recurrent theme in the papers read in New York. A subtext in Ryan Jones’ paper is the role played by organs of the state in calling on sexology as they ‘sought to forge the right kind of citizen-nationalist’, as he puts it. And if, in China, some of the ideas of Ellis were borrowed in the erection of ‘Chinese forms of epistemic modernity’, as Rachel Hui-Chi Hsu terms them, similar practices were at work in India. There, as Shrikant Botre and Doug Haynes observe, sexuality became central to a larger societal project of modernity; consequently, the Indian writer R. D. Karve must be seen not simply as an agent of westernization but as a translator of western ideas in the context of Indian nationalist politics.

Nowhere, perhaps, was the role of sexology in the practices of modern state-building more in evidence than it was in Prague in 1968. There, at the formidably sounding ‘Symposium sexuologicum Pragense’, as Kateřina Lišková notes in her paper, experts slogged it out over the causes of ‘deviant’ behavior, the nature of those causes suggesting roles the state might play in articulating specific solutions to perceived social problems. Despite their many differences, one thing these experts all shared in common, evident in the very title of the symposium itself, is the fact that they all came together under the disciplinary rubric of sexology. As I’ve suggested in these brief remarks, the papers on the three AHA panels discussed here break new ground: they force us to see sexology as a global phenomenon in ways we often have not before; by focusing on the circulation of ideas rather than on one-way influences, by exploring the context in which ideas were received and reconfigured, and also by detailing the work those ideas did in modern state-formation, they ask new questions of sexology and bring new disciplinary tools to its study. And yet they largely take the term ‘sexology’ as a given rather than interrogate it and examine the practices of disciplinary formation. Sometimes we historians concoct the field of sexology, creating a fabricated unity in order to legitimate our own studies; we articulate as a coherent field the disparate objects of our curiosity and desire. But perhaps we should also begin to examine the ways in which numerous global intellectual and political transactions, taking place over many decades, were themselves central to the making of the very discipline that is currently, and impressively, now being mapped as a global formation.

Chris Waters is Hans W. Gatzke ’38 Professor of Modern European History at Williams College. He is co-editor of Moments of Modernity: Reconstructing Britain, 1945-1964 and author of British Socialists and the Politics of Popular Culture, 1884-1914. His recent work focuses on British queer history, on which he has published articles in GLQ, the Journal of British Studies, and History Workshop Journal, amongst others. He is currently writing about three lives that in different ways dominated discourses about male homosexuality either in or about 1950s Britain – Alan Turing, Oscar Wilde, and Peter Wildeblood.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com