The Institute of Sexology at the Wellcome Trust is the first major exhibition in the UK dedicated to the history of sexology. Billed as a ‘candid exploration of the most publicly discussed of private acts’, it seeks to capture the imagination of prospective audiences with the deliberately provocative invitation to ‘undress your mind’.

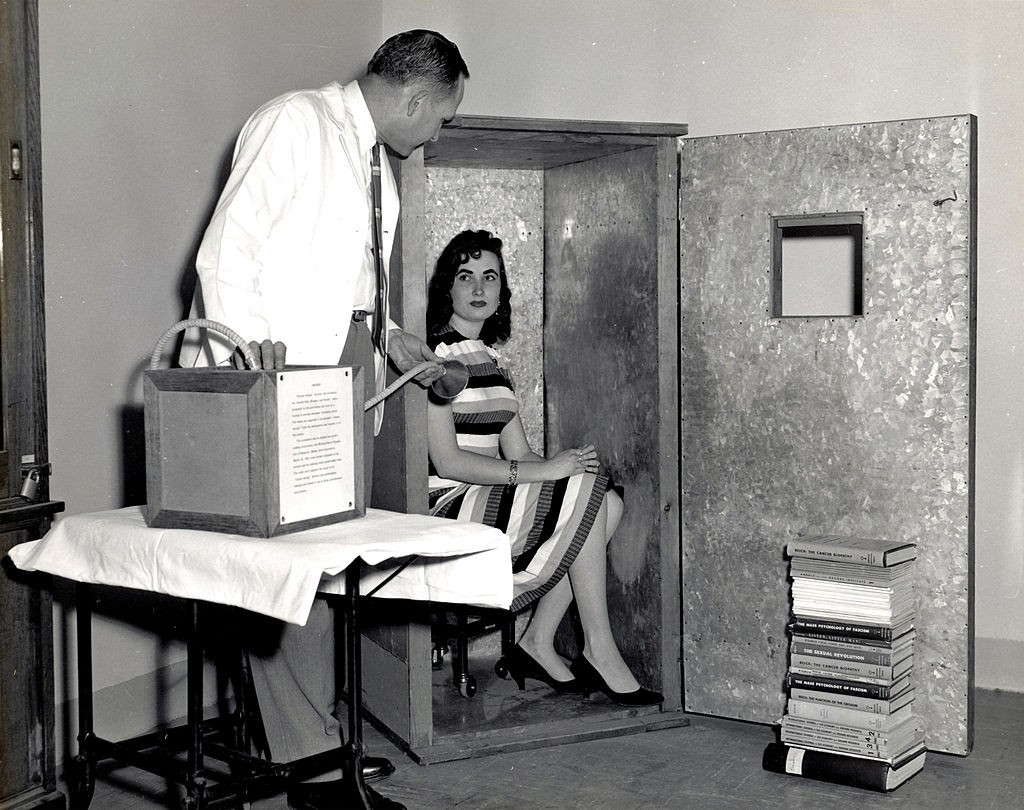

The curator of the exhibition, Kate Forde, certainly has an eye for the absurd and humorous aspects of the modern history of sexology – the whimsical display of sex toys or the pedestal exhibit of Wilhelm Reich’s ‘orgone accumulator’, intended to accumulate libidinous energies of those who sat inside it, indicate this. However, The Institute of Sexology takes seriously the business of sex research.

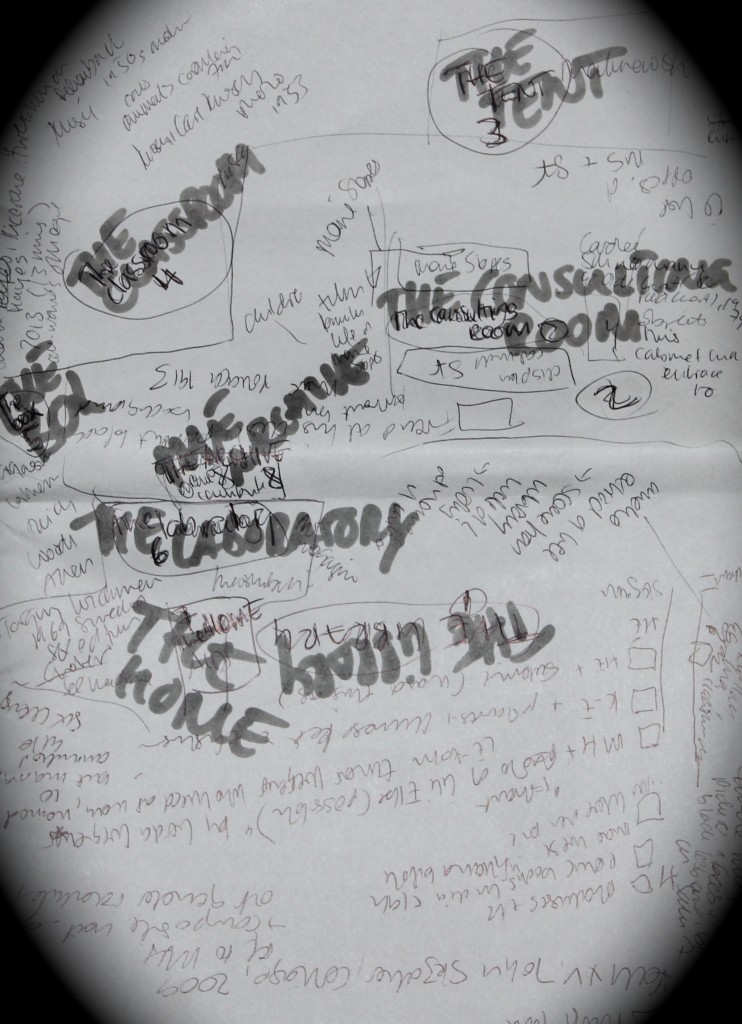

Reflecting the fact that the exhibition is primarily about sexuality in central European, British and North American contexts – other parts of the world appear largely within an anthropological framework – The Institute of Sexology is organised in a series of ‘rooms’ that indicate where ‘Western’ sex research has taken place. Visitors enter via ‘the library’ and then make their way through ‘the consulting room’, ‘the tent’, ‘the classroom’, ‘the box’, ‘the laboratory’ and ‘the home’ before exiting via ‘the archive’. As they embark on this journey, visitors move from the later nineteenth century – the point in time when the discipline of sexology emerged – into the present, where they are confronted with an invitation to record their own thoughts and ideas, thus contributing to an ever-expanding archive of sexuality.

While the chronological structure of the exhibition follows conventional histories of sexual science, the spatial organisation of The Institute of Sexology raises pertinent questions about the critical and cultural locations of sex research and how they mediate our relationship the archives of sexology.

The title of the exhibition alludes to Magnus Hirschfeld’s famous Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin. Founded in 1919, the Berlin Institute was the first of its kind. Before visitors learn about the Institute’s work, they encounter a visible reminder that it – and the period sometimes known as the ‘first phase of sexological research’ – came to a violent end. Projected on the far wall of ‘The Library’ is a black-and-white silent film which documents the aftermath of the Nazi attack on Hirschfeld’s Institute. On 6 May 1933 Nazi students and members of the S.A. raided the Institute, removing most of its library, and eventually setting fire to the looted books and papers on Berlin Opernplatz, an event that marks the beginning of the infamous Nazi book burnings.

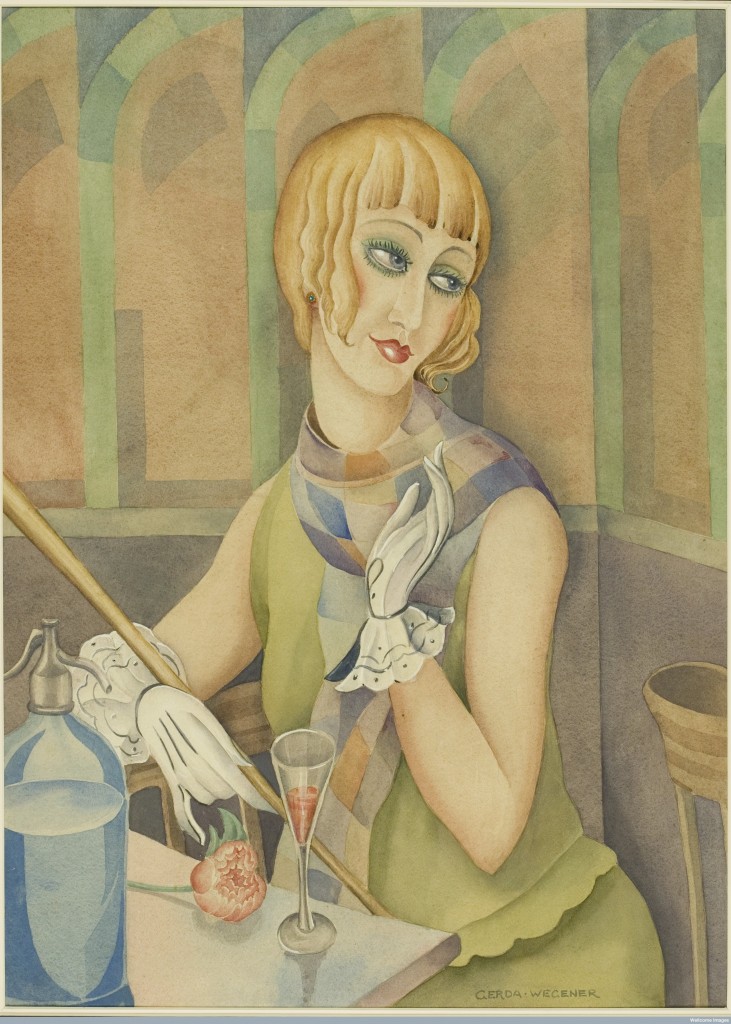

Given that arguably the most famous member of the Institute of Sexual Science was its Jewish and homosexual founder, it is perhaps not difficult to see why the Institute became a point of attack so early on in the Nazi reign. But it is equally important to note that the Institute’s activities were wide-ranging including, for instance, birth control advice and marriage counselling as well as homosexual rights activism and support for an emerging transgender community. The head of the gynaecological department, Ludwig Levy-Lenz, performed the first sex change operations, including that of Lili Elbe who, after a series of surgeries, died in 1931 after a failed uterus transplant operation. (A film about Elbe’s life, The Danish Girl, is due to be released in cinemas later this year). The exhibition features a portrait of Elbe, painted by her partner Gerda Gottlieb, alongside images of Magnus Hirschfeld and other sexologists.

The inclusion of Elbe’s portrait, opposite a photograph of Radclyffe Hall and her partner Una Troubridge, in the opening section of the exhibition marks one of the most important critical interventions of the Institute of Sexology: its emphasis on gender in the history of sexology. Recent scholarship has shown that literature, visual imagery and other forms of cultural production played a vital role both in the articulation of modern ideas about gender and sexuality, and the emergence of collective identities centred on these terms. Radclyffe Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness (1928), for instance, famously prompted the first public debates about lesbianism in Britain. The Institute of Sexology takes care to represent cultural critiques alongside the ‘scientific’ work of both female and male sex researchers, often in provocative ways – the ‘consulting room’, for instance, is shared by Sigmund Freud, Marie Stopes and the radical feminist artist Carolee Schneemann, whose Ye Olde Sex Chart (Sexual Parameters Chart) (1974) troubles assumptions about the diagnostic work of sex research.

The feminist framing of The Institute of Sexology has come as a welcome surprise for me. It reminds me of Judith Butler’s argument in Precarious Life, a study of American public discourse post 9/11, that the way in which debates are ‘framed’ shapes whether or not the very existence of certain lives can be apprehended, or ‘heard’. Research on the history of sexology has struggled with the question of how to ‘hear’ the voices of those subjects in the past whose lives have left little material traces in the historical archive, or whose stories have been (re)written or excluded by sexologists and the structural gender inequality and racial oppression within which this work developed.

The Institute of Sexology ‘reframes’ how we approach the sexological archive by letting the voices of young women guide the visitor’s encounter with this history. Upon entering the exhibition, visitors hear the voices of a group of young women who are in animated discussion about sexual politics. The voices, which belong to students from Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, are part of a video installation by Sharon Hayes. Entitled Ricerche: three (2013), it can be found roughly half way through the exhibition, in a section entitled ‘the classroom’. The video shows a group of young women debating the value and limits of gender-segregated education, and thus also tackling a wide range of issues relating to contemporary sexuality. While the video is fixed in a space where it provides the counterpoint to the exhibit of Alfred’s Kinsey influential theories on sexual behaviour, the young women can be heard in every part of the exhibition. As they report on their own experiences and argue about the meanings of ‘sex’, the voices of these young women accompany visitors on their journey through the history of sexology.

This, for me, is The Institute of Sexology’s most important intervention: its feminist play on the queer history of sexuality.

Hear, hear.

The Institute of Sexology exhibition at the Wellcome Collection, London runs 20 November 2014 – 20 September 2015.

Heike Bauer is a Senior Lecturer in English and Gender Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. She has published widely on the history of sexuality, nineteenth and twentieth century literary culture, and on translation. Her books include English Literary Sexology, 1860-1930 (Palgrave, 2009), the 3-volume edited anthology Women and Cross-Dressing, 1800-1939 (Routledge, 2006), and the edited collections Queer 1950s: Rethinking Sexuality in the Postwar Years (Palgrave, 2012, with Matt Cook) and Sexology and Translation: Cultural and Scientific Encounters Across the Modern World (Temple, 2015). She recently co-edited with Churnjeet Mahn a special issue of the Journal of Lesbian Studies on “Transnational Lesbian Cultures”, and is currently completing the AHRC-funded study A Violent World of Difference: Magnus Hirschfeld and the Shaping of Queer Modernity. Heike tweets from @Heike_Bauer.

Heike Bauer is a Senior Lecturer in English and Gender Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. She has published widely on the history of sexuality, nineteenth and twentieth century literary culture, and on translation. Her books include English Literary Sexology, 1860-1930 (Palgrave, 2009), the 3-volume edited anthology Women and Cross-Dressing, 1800-1939 (Routledge, 2006), and the edited collections Queer 1950s: Rethinking Sexuality in the Postwar Years (Palgrave, 2012, with Matt Cook) and Sexology and Translation: Cultural and Scientific Encounters Across the Modern World (Temple, 2015). She recently co-edited with Churnjeet Mahn a special issue of the Journal of Lesbian Studies on “Transnational Lesbian Cultures”, and is currently completing the AHRC-funded study A Violent World of Difference: Magnus Hirschfeld and the Shaping of Queer Modernity. Heike tweets from @Heike_Bauer.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Reblogged this on A Violent World of Difference.

Really perceptive piece 🙂 I visited this exhibition over the weekend and was also struck by the way the young women’s voices from the video echoed through different rooms and stopped so many visitors in their tracks. The feminist perspective provided by this and other aspects of the exhibition was really welcome. “Gender matters” in several senses, though, and I was equally struck by the fact that (with the exception of a portrait of Lili Elbe) the representation of trans experiences was confined to one corner at the end of the exhibition – “oh look, it’s the trans corner!” –

containing a hard-to-navigate and relatively decontextualised webcomic. Perhaps there’s scope for more exploration of the interplay between trans history and the history of sexology in the future?

Just found this piece having searched for a string of words to find the name of the filmmaker of the Mount Holyoke piece. I loved that film. I sat there in the gallery and cried feeling such identification with those young women and a kind of empowerment I hope they never lose. I’m sure the film wasn’t intended to produce that feeling of nostalgia 🙂