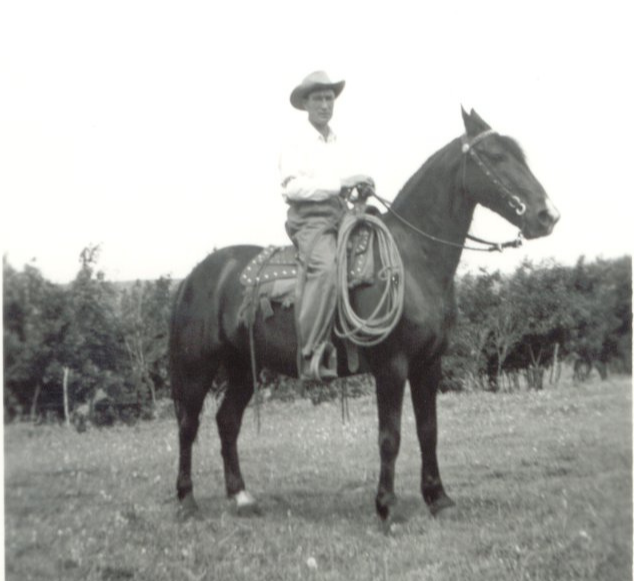

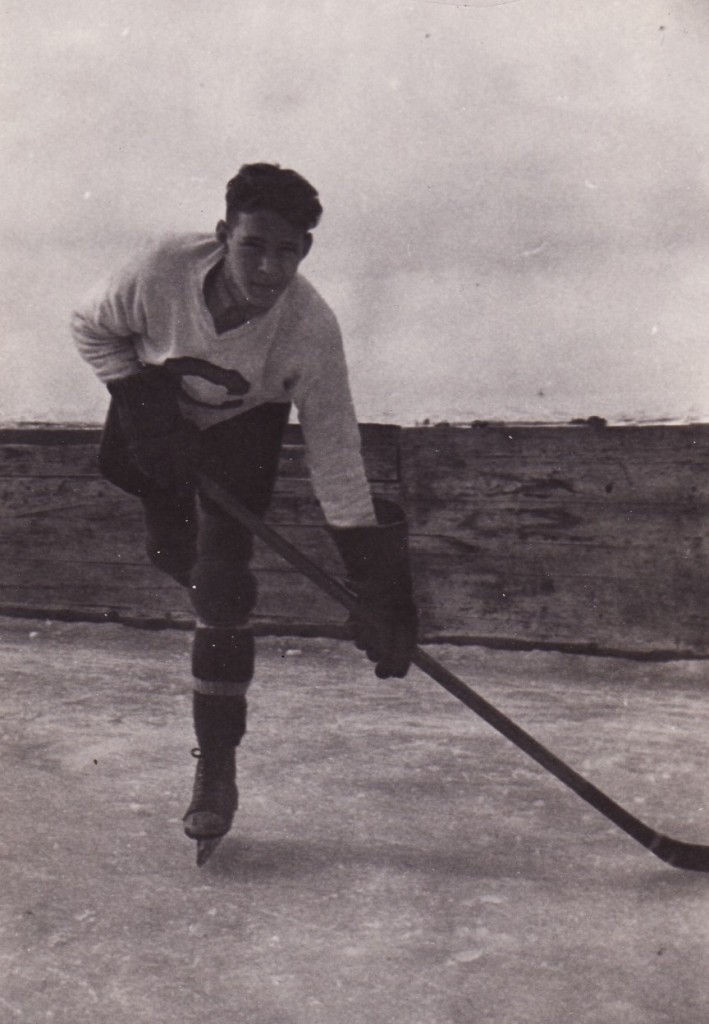

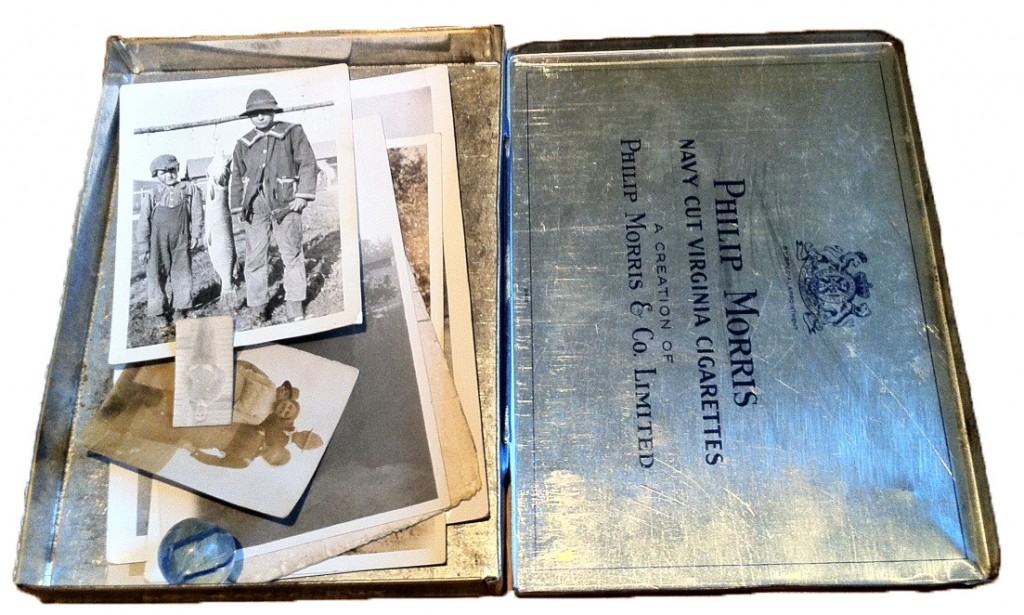

I never knew my great uncle Cecil Bengry. Affectionately known as Cic’, this bachelor uncle seems to have lived in the background of other people’s lives. Even the pictures of Cic’ in old age that I found among my own grandfather’s (his brother) papers are faded and overexposed, their physical condition seemingly recreating the fog that surrounds Cic’s life. We know that he spent most of his life caring for others: animals on the ranch, his mother in her old age, and his brother’s grandchildren in his own later years. They remembered Cic giving them treats of ‘sugar sandwiches’, and knew him as well as anyone could, yet they didn’t know if he had an education, if he had friends, even what he did during the day. He is remembered simply as ‘always there. Good to us.’ Though always around, Cic’ somehow remained unknown. When he died, Cic’ left only one record behind: a small cigarette tin of photos. Inside, along with a child’s glass marble and a few family pictures, were snapshots of numerous men, including one of a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer I call the ‘sultry Mountie’.

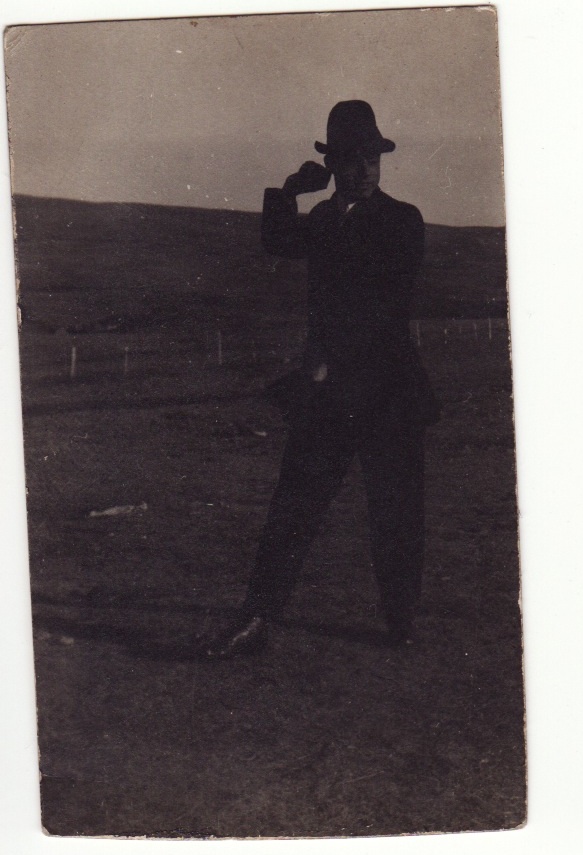

Unlike every other photo in the tin box, the picture of the Mountie included no information: no caption, no name, no date. He simply stands there, anonymous, leaning casually against a wooden rail with hips thrust forward, looking confidently and directly at the camera. Posing for effect, he invites observation and perhaps objectification. I struggled to understand this image and the homosocial collection of photos with which it came. The tin of photos inspired me to organize, with Amy Tooth Murphy, workshops on what we called ‘Queer Inheritances’ at the London Metropolitan Archives in December 2014. We wondered: How do we discern a queer life from incomplete personal effects whose existence and content are often mediated by other family members? How do we, as queer inheritors, navigate lives lived before many could proclaim to be ‘out and proud’? Ultimately, I wondered, was Cecil queer?

Cecil Bengry was born in 1905 and raised in the foothills of Canada’s Rocky Mountains. According to family stories, he worked on the family ranch, aiding his parents. And when they moved into town in old age, leaving the family homestead to his brother Joe, Cic appears to have followed them. After his father died, he cared for his ailing mother, finally joining Joe’s family in British Columbia by the time of their mother’s death in 1954. Living with Joe, and by now nearly 50 himself, Cic’ was his brother’s companion, ‘chief cook and bottle washer’, and helped to care for Joe’s grandchildren. He lived simply, remembers one of those children: ‘His room was upstairs. A window. Neat and tidy. A simple but nice armoire for his clothes. A red child-sized chair beside his bed. An ashtray, brown seashell and an iron dog sat upon it.’

Cic’ died in 1971 and Joe inherited his meagre possessions. (Joe lived another 20 years, and I remember meeting him when he was nearly 100.) ‘Old Joe’ was a meticulous hoarder of family and local history who saved everything: papers, diaries, artefacts, notes, recipes, slips, books, dirty stories from 1912, even a prophylactic from WWII. An incredibly self-aware curator of his own life history, Joe labeled, relabeled, corrected and annotated family photos. Nothing passed through Joe’s hands unmediated. When Cic’ died, Joe incorporated his brother’s possessions into his own archive, and it is through these that we gain some sense of Cic’s life and perhaps what was important to him. Joe gave that small cigarette tin a simple label: ‘Cic’s photos’. It later passed to my cousin, being the oldest son of the oldest son of the oldest son. (The Bengrys are rather fond of primogeniture!) Being the youngest son of the oldest son of a middle son, I’ve fared less luckily in acquiring family treasures, but my cousin kindly gifted Cic’s cigarette tin to me.

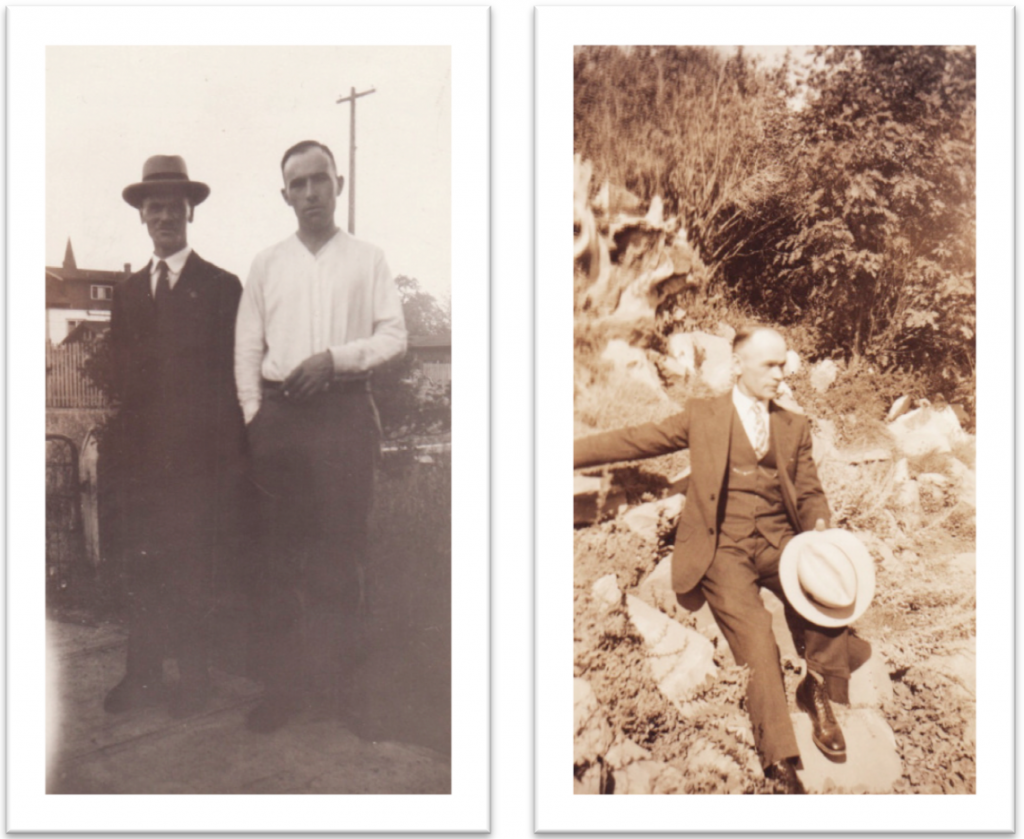

Amid a couple family and childhood photos including one of Cic’ with his brother Ernest, who died aged 18 in 1929, other photos in Cic’s collection require more scrutiny. The remainder comprises a collection of men, including the sultry RCMP Officer. Several photos show two men in particular and were originally labelled with a fountain pen in a careful hand (Cic’s?): ‘They two Villains Woodruff & Bert’. Joe has corrected the label much later using a ball point pen and his scratchy hand to include a note of a very different tone: ‘Old friends and neighbors of mother Bengry & family, Cardston’. Cic also saved and labelled pictures of local male school teachers, likewise ‘corrected’ by Joe, who were active in rural southern Alberta and died in the First World War. One, from Nova Scotia, came out west as a young man to teach before going to war. Another photo is just a few centimeters in length. All these photos are annotated in multiple hands. And yet not a single mark appears on the photo of the Mountie.

What are we to make of this collection of men’s pictures? They could, of course, simply be the record of a lifetime of memories of the friends and acquaintances of a confirmed bachelor. But the number of men in the photos, their poses, even the marginality of some as itinerant, rural male school teachers raises questions. Could this collection speak to a queer life on the Canadian prairie in the years between the wars, and perhaps beyond? Is it possible that this unassuming cigarette tin illuminates a history of queer lives outside of the cities and spaces where we more easily recognize them?

Family folklore about Cic is sparse. My cousin’s mother remembers asking outright as a child why Cic’ never married. He answered that there wasn’t a woman out there for him, and that he didn’t think much of marriage anyway. She remembers it all seeming very final. Was this an empty statement to end an impertinent question, or a more poignant clue shared safely with a child? Whatever Cic’s sexuality, and I use the term cautiously, he did live outside of normative expectations of adult masculinity. Queer, then, can be a useful term for thinking about Cic’s life. We have no concrete reason to believe Cic’ ever identified as homosexual. But nor did he live a typical life, and his experiences don’t neatly break into binary gender roles. The many silences in Cic’s life encourage questions, and open up conversations.

Whatever Cic’s understandings of himself were, we know from historians working in other regions of North America and Europe at this time that sexual fluidity between heterosexuality and homosexuality was not uncommon. Indeed, scholars have concluded that fixed understandings of sexual binaries, that we now take for granted, seem to have solidified only some time after the Second World War in many western countries. Helen Smith has previously written here at Notches about working-class men in England’s industrial North who, until at least the 1950s, accepted homoerotic encounters and even sex as being compatible with ‘normal’ — what we might imperfectly term heterosexual — manhood. Nor did wives, families, or communities find their actions incompatible with local norms.

Whatever Cic’s understandings of himself were, we know from historians working in other regions of North America and Europe at this time that sexual fluidity between heterosexuality and homosexuality was not uncommon. Indeed, scholars have concluded that fixed understandings of sexual binaries, that we now take for granted, seem to have solidified only some time after the Second World War in many western countries. Helen Smith has previously written here at Notches about working-class men in England’s industrial North who, until at least the 1950s, accepted homoerotic encounters and even sex as being compatible with ‘normal’ — what we might imperfectly term heterosexual — manhood. Nor did wives, families, or communities find their actions incompatible with local norms.

The term queer is also useful in the present because it provides a way to frame how we look at the past. It gives me other ways to think about Cic’ and his life. How much am I, as a twenty-first century gay man, projecting onto Cic’? In a search for some kind of ‘queer inheritance’ am I creating rather than discovering a queer forebear in the family? I’m unwilling to assign to Cic’ any kind of ahistorical sexual identity based on my own understanding of myself. But I – and my cousin, who’s gaydar first picked up on Cic’ in ways that ‘Old Joe’ Bengry may well have missed (or not) – am also sensitive to recognizing layers of sexual diversity and fluidity in the past.

We are unlikely ever to uncover the ‘truth’ of Cic’s sexual identity. But engaging with Cic’ allows us to think about the past differently, and also to engage with the present. For queer men and women today, it’s critical to see that there is a queer history, many queer histories in fact, even if they don’t map precisely onto today’s understandings of LGBT. As my cousin who first found Cic’s collection put it:

That’s the question of alone-ness, of reflection … of seeing oneself reflected somewhere, and most importantly in family … Surely I’m not the only pink sheep in the family. But that question is there for those long dead too: surely I’m not the only one who has ever loved men. Surely I have gay forebears somewhere. For me, Cic’s possibility means my possibility.

All of which brings us back to ‘queer inheritances’ and the possibility of doing family history queerly. Surely the quest for a queer past is more powerful at the more intimate level of family, in the networks of kinship, and the familiarity of photo albums passed on from loved ones. Going beyond the lists of so-called ‘famous queers’ of the past, queer family history locates us in a shared history; it gives us a history in which to place ourselves.

And so we need to talk about Cecil, and about the men and women like him whose experiences may not conform to easy binaries and familiar categories, and who have often left no more than a cigarette tin to stand in testament to their complex and unknowable lives. For in those photographs are images, desires and possibilities.

Justin Bengry is an Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. Justin’s research focuses on the intersection of homosexuality and consumer capitalism in twentieth-century Britain, and he is currently revising a book manuscript titled The Pink Pound: Queer Profits in Twentieth-Century Britain. He tweets from @justinbengry

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Fantastic post, Justin. Tantalising photographs and glimpses of possible lives.

Thanks so much! It was a fun piece to write, but has opened up more and more questions. But that’s part of the fun too!

Great, thoughtful piece. Interesting that the Mountie seems to be in a port town, unlike the other photos.

Thanks for your comment. I’d noticed that too about the port town, and assume it’s the Vancouver or somewhere on the West Coast of Canada. But I’ve not uncovered any information about Cecil travelling that way for any length of time. Of course, it might only have been a short trip, or a photo taken somewhere other than where they’d met (or even a photo of someone he never knew, but saved nonetheless). So many questions!

Interesting and fascinating post. I enjoyed it very much.