In 1960 Patrolman John Mindermann, a rookie officer in the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD), was assigned to San Francisco’s Polk Gulch neighborhood. On his first night out, he stumbled upon the Cable Car Village, a gay bar. Speaking with me years later, he recounted this discovery and his feelings of confusion and vulnerability:

I stopped as I go [sic] inside the front door. And I’m shocked because I see nothing but men down the bar, and in the back. . . there’s, I guess, a small dance floor, because I never quite got back that way. And I see men dancing with each other. . . . [Laughing] I’ve never seen anything like this! . . . Could this be a—in the parlance of SFPD, could this be a fruit joint? . . . And everything stops when they see me. Everybody’s apprehensive. They’ve never seen this guy before, you know. . . . And I go, I better not do anything because there’s so many of them, and there’s just me, and I have no radio. . . . So I back out and I go about my diligent business.

As Mindermann’s recollections of bewilderment illustrate, postwar law enforcement leaders rarely prepared patrol officers for the day-to-day policing of gay and lesbian people. Instead, departments expected their patrol officers to use their discretion. Officers could enforce formal legal codes over gay and lesbian bars. Often they extorted money from these establishments. These police demands for payoffs sparked resistance from gay bar owners and set the stage for a wider campaign for professionalized policing and liberal sexual standards in San Francisco.

Police like Patrolman Mindermann entered the post-World War II period with vast discretionary powers over San Francisco’s LGBT residents. Unexpectedly, the politics of redevelopment opened an opportunity for gay-bar owners to challenge that discretion. During the 1950s, urban reformers began viewing police extortion as an obstacle to federal redevelopment grants, and they therefore launched a movement against police corruption. Gay-bar owners achieved a civic voice by placing themselves at the forefront of that professionalization campaign. Ultimately, these gay-bar owners used the politics of discretion to forge a new enduring liberal coalition and ideology.

After World War II, the nation’s urban police leaders occasionally ordered bar raids and neighborhood sweeps, but they seldom directed policing during the long stretches in between those high-profile police actions. In most cities, the day-to-day policing of gay and lesbian bars fell to beat officers. For most of the 1950s, police in California could not prosecute a bar for simply allowing gays and lesbians to congregate. But if patrol officers wished to express antigay animus or regulate a bar’s visibility, they could choose from a variety of harassment tactics. For instance, officers could use subjective noise ordinances or arrest patrons with vague status-based codes, such as “vagrancy.” Often, police officers preferred tactics that limited their physical contact with gay and lesbian people. One approach that required minimal intimacy was to demand payoffs–known as “payola”–from a bar’s owner.

Payola had played a central role in urban American governance since the nineteenth century. Urban political machines commonly appointed cronies to plum positions within city agencies like the police department and then expected those appointees to fill machine coffers with extortion payments. Police officers permitted discrete gambling dens, prostitution houses, abortion clinics, and homosexual bars to operate in exchange for payoffs, and the officers themselves profited by pocketing a small fraction of the payola.

This corrupt arrangement encountered a new challenge, however, in 1949 when the federal government began offering cities funds for large-scale redevelopment. In order to receive these grants, city officials simply had to conduct studies illustrating that an area was “blighted” and present a competent plan for redevelopment. Downtown business leaders stood to make fortunes off of the subsidized razing and rebuilding of the urban core, but they often found that machine cronies lacked the expertise and motivation to craft grant applications. As a result, postwar downtown elites began looking for reformers who would professionalize city government.

In San Francisco, downtown elites backed George Christopher, a clean-government reformer, in the city’s 1955 mayoral election. Christopher positioned himself as a candidate for the people—rather than a lackey for elite business interests—by insisting that his professionalization agenda would defend the interests of male heterosexual breadwinners and their families. In the San Francisco News-Call Bulletin, Christopher charged that machine officials condoning an “open town” of “vice” establishments only “care about…the fast buck. They don’t care where they get it—whether it’s from your daughter or the kid next door.” Christopher tied together downtown development, government professionalization, and traditional family values into a single agenda and thereby won the 1955 election by the largest margin of victory in San Francisco history.

Although Christopher championed “family values,” his dedication to clean-government reform opened an opportunity for gay and lesbian owners of bars. In 1960 Christopher had finally staffed his government’s top-tier positions with reformers and downtown business leaders assumed that this efficient government was ready to support urban development projects. A group of gay-bar owners realized that Christopher’s elite support hinged on his ability to root out corruption. They revealed to the mayor that beat officers were demanding payoffs from the city’s downtown gay drinking establishments and threatened to go public with this information. With his reputation and coalition at stake, Christopher worked with gay-bar owners to entrap corrupt officers. In fewer than four months, a grand jury indicted three sergeants, two patrolmen, and one state liquor agent. The rank-and-file police named the payola scandal gayola.

Although Christopher helped free the city’s gay and lesbian bars from organized police extortion, the clean-government alliance between Christopher and the gay and lesbian bar owners proved short-lived. The mayor remained committed to a heterosexual standard of citizenship, and after the gayola trials, he ordered raids against the city’s gay and lesbian drinking establishments. Within a year, law enforcement shuttered all of the bars involved in the gayola trials.

However, the trials planted the seeds for a second, more resilient reform coalition. San Francisco’s downtown redevelopment was attracting thousands of young white-collar workers into the city. These professionals desired clean government as a path to downtown growth, but they often arrived in the city childless and relatively uninterested in traditional family values. Instead, the young migrants hoped clean governance would produce a profitable and culturally diverse San Francisco.

The gay prosecution witnesses in the gayola trials presented themselves as potential partners in that project, and San Francisco’s young white-collar workers received the message. During the trials one young liberal journalist for the San Francisco Chronicle expressed little concern over the reported harassment of gay and lesbian people, but he ribbed a “husky [and] solemn-faced” sergeant for using his discretion to stifle gay commerce. When the officer testified that he had forbidden a gay-bar performance that was “one of the lewdest I believe I’ve ever seen,” the reporter quipped that the officer “‘Censored’ Gay Bars” and questioned why “he alone decided when the shows got too rough for the customers.”

The debates over police discretion thus allowed young downtown professionals and middle-class gays and lesbians to form a new “cosmopolitan liberal” coalition based on professionalized governance, downtown development, and broadened sexual standards. By the end of the 1960s, local candidates like Joseph Alioto and Dianne Feinstein were using these principles to win elections to City Hall.

This cosmopolitan liberal politics initially made San Francisco unique, but by the end of the Sixties and into the next decade, gay and lesbian activists used the politics of police professionalization to build bridges with white-collar workers in Los Angeles, Seattle, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Washington, DC. Sexuality scholars emphasizing sociocultural politics have often pointed to the broadening mores of the sexual revolution when explaining gay and lesbian coalition building in the second half of the twentieth century. Meanwhile, historians examining the development of the “straight state” have largely narrated the professionalization of the government as a process of increasing coerciveness. The gayola story integrates and amends the sociocultural and state development approaches. In cities like San Francisco, gay and lesbian owners of bars exploited the politics of police professionalization to both enter the civic sphere and claim rights as citizens.

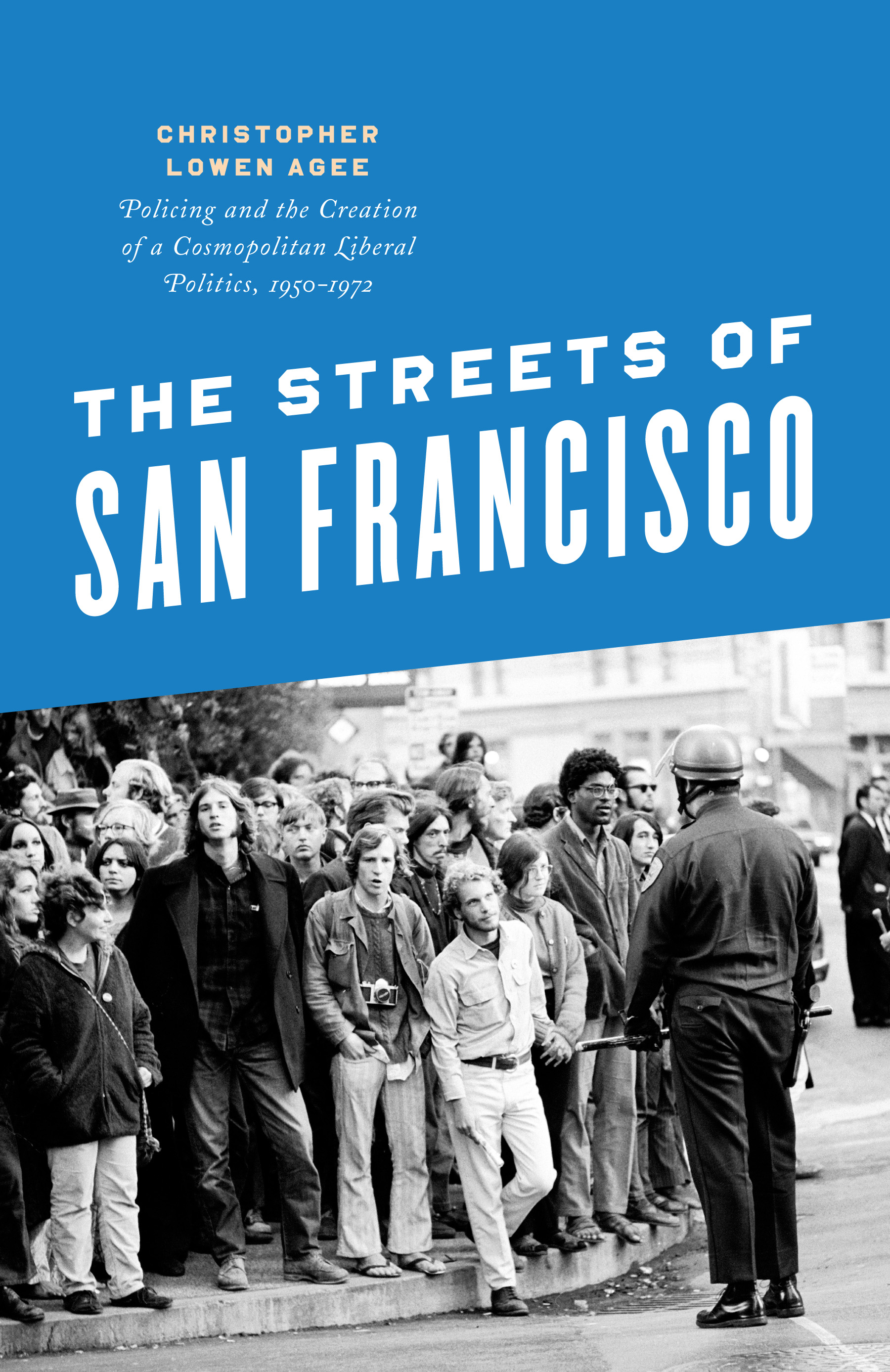

Christopher Lowen Agee is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Colorado Denver. His book The Streets of San Francisco: Policing and the Creation of a Cosmopolitan Politics, 1950-1972 (University of Chicago Press, 2014) has recently been published in paperback. His current research focuses on the 1980s and 90s and explores LGBT politics, community policing, and the concept of risk. In 2016 he will begin a term as an OAH Distinguished Lecturer.

Christopher Lowen Agee is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Colorado Denver. His book The Streets of San Francisco: Policing and the Creation of a Cosmopolitan Politics, 1950-1972 (University of Chicago Press, 2014) has recently been published in paperback. His current research focuses on the 1980s and 90s and explores LGBT politics, community policing, and the concept of risk. In 2016 he will begin a term as an OAH Distinguished Lecturer.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I lived in the Polk in the early 70’s. Wild times. Great stories. Thanks Christopher. Gerard Koskovich can tell you more…