Surveying the contemporary world, it is tempting for university students to position themselves as the liberators of sexuality, at least, that is what I so frequently witness when I teach my upper-division “Sexuality and Culture” course. My students are confident that they clinched marriage equality in the U.S.; they laud their employment of pan-, demi-, and poly-sexual as identity terms; they are cool enough to know hooking up is NBD – “no big deal.” When I ask them “who created sexting?,” though, they always look astonished, disgusted, and incredulous when I insist my grandparents helped pave the way for their virtual trysts.

That dismay grows when I project the image of my maternal grandmother flaunting her gams, sporting her 1940s version of “fuck me pumps,” wearing my grandfather’s flannel shirt and a “come hither” countenance par excellence. You see, the world was at war then, and Gram took her secret mission – satisfying my grandfather’s sexual urges and her own while they inhabited separate continents – quite seriously. Even as she scrawled “All my love, Nona,” in bluish-black ballpoint across the photo, she must have known that he wouldn’t be focused on her textual message. At least she hoped not.

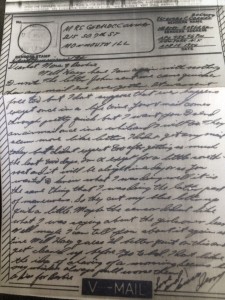

Gram was not messing around when she orchestrated the production of this “blue” photo. She had heard about French women – both from the Victorian novels she loved and from my grandfather’s tantalizing allusions in his V-Mail letters – and she was not about to lose her man to them, no matter how patriotic the cause. Before he departed for Europe, the two enjoyed a robust sex life, each of them evincing more than their fair share of sex appeal. Decades after, when I was a small child, my elders would quip and whisper about how gorgeous they had both been, chalking the happy early years of their marriage up to overpowering lust and animal magnetism. By the time Charlie Merrill – who ironically would later serve as my mother’s wedding photographer in 1967 – printed Gram’s photo as an extravagant 5×7 on 2 November 1944, they had been separated for two sexually frustrating years, during which even their textual communications became a form of coitus interruptus.

Papa, as we called him, had been trying desperately to convey his desire for Gram via his letters, but he makes clear in one dated 18 April 1944 that his textual sexual overtures were being redacted by a censor saying, “so they cut my blue letter up quite a little.” He continues on, “maybe the censor didn’t like what I was saying about the girls over here.” Clearly, Gram sensed the competition and the dire urgency of the “blue,” and took matters into her own hands. Interestingly, these mementoes of their mutual love and desire were never kept hidden, as is the case with so many archives of this nature. My mother recounts being familiar with this photo, though not Papa’s letter, from the time she was a child. She jokes that the photographer who printed the photo – sadly, we do not know who actually took it – was also titillated by Gram’s display and often made eyes at her whenever he got the chance, even decades later.

Once they have confronted these items from my personal archive, students struggle to deny that my grandparents were clearly engaging in behaviors similar to their own sexting, only using the technology available to them as best they could. What proves most interesting in this interaction, though, transpires when I highlight the absolute lack of privacy inherent in these exchanges. My grandfather, in defiance of censorship, still clearly expressed his erotic desires to my grandmother, knowing all the while they were likely to be redacted. This, of course, raises the question of whether the presence of a third party in this transaction further energized his desire. Gram, for her part, had no option but to take her film to a processor – and one she knew well, no less. Her desire, too, appears to have been heightened by Merrill’s seeing and knowing to whom she was sending her cheesecake shot, suggesting that the phenomena of intercepting and publicizing erotic/sexual communication enjoys a much longer history than those who came of age in the era of sexting likely realize, especially when they discover that getting caught may play an integral role in the fun.

Of course, after we critiqued all this, we then have to return to the fact that I am quite aware of my grandparents’ rambunctious, raucous, maybe even raunchy, sex life because while students may finally accept that they did not invent sexual communication, they gladly participate in a tradition much older: refusing to admit their grandparents were hot for one another. Just as they begin to grapple with that possibility, I further complicate their claim to cornering the market on sexual photography by introducing them to a range of sources both popular and academic which reveal that my grandparents were not exactly trailblazers in that arena either, as they were merely the latest innovators in a tradition launched probably moments after the camera’s invention. Offering my students this snapshot of photography and sexual desire proves deeply satisfying. We journey forth with an enhanced awareness that technology and sexuality shared a long, storied past, and that just as quickly as innovation occurs we humans then start to experiment with its intermingling in our sexual lives and expressions of desire.

Joshua Adair is an Associate Professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as director of the Racer Writing Center and coordinator of Gender and Diversity Studies. He has published about the work of Beverley Nichols and Christopher Isherwood, as well as the presentation of queer lives in historic house museums.

Joshua Adair is an Associate Professor of English at Murray State University, where he also serves as director of the Racer Writing Center and coordinator of Gender and Diversity Studies. He has published about the work of Beverley Nichols and Christopher Isherwood, as well as the presentation of queer lives in historic house museums.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

It’s quite interesting to note that a teacher teaches through his or her own family history. Incidentally, sexual communication is much older than even Josh’s maternal grand parents’ sexting through letters & photos: in the Kāmasūtra also a sort of sexual communication is done through leaving one’s teeth marks on letters and gifts that the prospective lovers exchange.

If we closely look within our family histories, Josh-type heirlooms might come up. I had one short story written by my dad! Now lost though. But Josh’s doubtless the best. It’s courageous of him too: we need such people. But don’t expect this from Indians.