From pay-dirt moments and unexpected, visceral intimacies to the arduous, lust-dust-fever drive, researchers feel in and about archives. The root of my desire to think about the archive is—no joke—rooted in desire. For me, archival discoveries at Cornell University’s Human Sexuality Collection,Texas A&M’s The Don Kelly Collection for Gay and Lesbian Literature and Culture at the Cushing Memorial Library, and Duke University’s Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library have bookended this exploratory journey into a past that I’ve learned is a part of my everyday present.

Just a month or two before my edited book, Out of the Closet, Into the Archives, really began to take shape, I sifted through old notes and file folders from an archival visit during the previous year. Sandwiched between my annotations on a 1970s lesbian feminist writing collective journal from North Carolina, photocopies of poems from the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and papery pink and yellow-tinged library call slips, was a forgotten letter I’d excitedly jotted to an old lover about what I’d just seen and touched in the reading room. As I wept and read the undelivered note, what struck me most was how reflective and reflexive this work could be. I’m talking about feelings, and the material artifacts of academic life. I couldn’t stop thinking about the archive, and now, my archive, alive with its own emotion and intelligence.

These and other accounts of archival attachment—informed by concepts of the archive that range from power and authority (Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida) to formulations of the archive of happiness or archive of emotion and trauma (Jack Halberstam, Ann Cvetkovich, Sara Ahmed)—moved me and Amy L. Stone to ask, “How might we acknowledge the affective investments that motivate, draw on, or contribute to the ‘archival turn’?” As contributors’ own experiences in queer archives and queer archival collections eventually shaped the volume’s organization, so too did difficult epistemological questions: What do we think we know about the queer lives about which we write? Is “proof” even something the archive can offer? What’s at stake in thinking about how queer archival scholarship transmits emotions alongside a host of compelling methodological practices and tensions?

Out of the Closet, Into the Archives illustrates how archival research offers a profoundly queer temporal and tactile experience—and temporary existence—for scholars engaging in the study of queer lives and sexual histories. Authors question how our identities, research questions, and emotions are determining, shaping, and puzzling the reading room’s (or basement’s, or garden’s, or home movie cabinet’s) curiosities and discoveries.

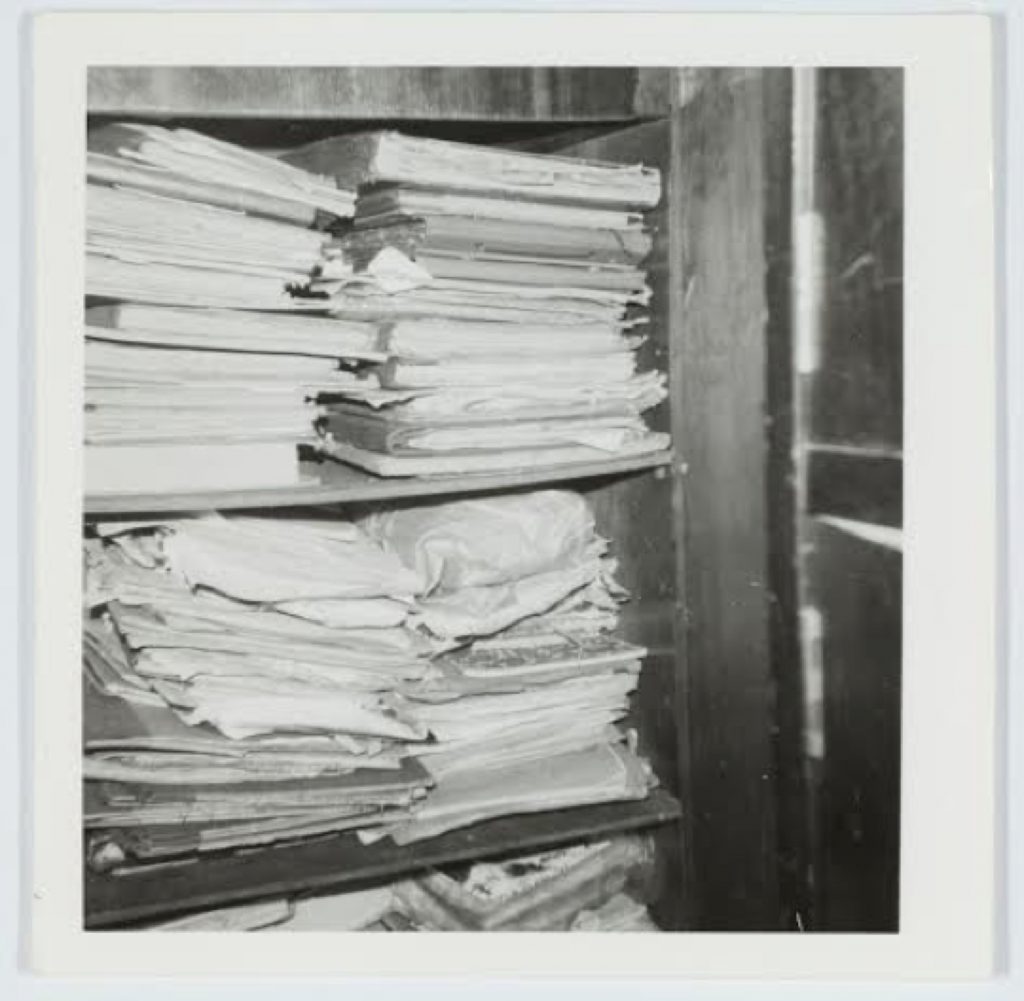

The volume is divided into four parts that address pressing issues in LGBTQ archival research: archival materiality, beyond the text, archival marginalization, and cataloguing queer lives. The first section focuses on the space of the archive itself and access to its holdings, from the institutional and heteronormative forces that define repositories and determine their collections, to concerns surrounding staffing, storage, and preservation. The volume begins with Agatha Beins‘ comparison of conventional archives like the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College with counterarchives such as the Lesbian Herstory Archives, analyzing how archival space affects the researcher’s experience, reinforces boundaries, and defines what counts as archival object. Craig Loftin’s chapter describes his experiences researching letters to ONE Magazine in the ONE Institute Archives. As a volunteer cataloguer with his own key to the building, Loftin argues that his work in counterarchives blurs the boundary between historian and archivist.

The second section seeks to understand the archive’s non-textual materials, encompassing video tapes, buttons, audio files, t-shirts, and photographs. Whitney Strub explores a massive, bootlegged VHS porn collection from an individual he calls The Archivist. This erotic archive, and other “obscure archives of smut” provide evidence that “gay desire persisted even in the worst of the plague years of the AIDS epidemic.” Greg Youmans‘ chapter explores what is poorly contained in the conventional archive, by analyzing poet Elsa Gidlow’s garden—extant plants and seeds. Youman thus models an embodied and creative approach to studying the ephemeral nature of LGBTQ lives. Julie Enszer’s contribution offers “a materialist narrative about lesbian-feminism” and documents the perverse pleasures found in materials that do not conform or fit into the archive, including her discovery of poet Minnie Bruce Pratt‘s vibrator at Duke University.

The third section interrogates archival omission, injustice, and erasure; specifically, the marginalization of black, Chicano, and trans* lives in LGBTQ archives. Robb Hernández analyzes queer points of encounter, sexual disclosures, and AIDS cultural memory in oral history transcripts of Chicana/o artists complied by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Rebecca Fullan’s chapter examines the Essex Hemphill/Wayson Jones Collection at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

The final two chapters in this section analyze the ways in which trans* narratives and histories are frequently ignored, misunderstood, or co-opted within queer archives. Liam Lair provides his account as a trans* researcher interacting with these stories in the Lawrence Collection at the Kinsey Institute. Aaron H. Devor and Lara Wilson describe the serendipity and groundwork involved in establishing the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria; they map development issues and barriers, while exhorting librarians and archivists to “familiarize themselves with the trans* history, activists, advocates, and organizations whose history has been saved.”

The concluding section of this volume focuses on autobiography, agency, and the ways LGBTQ lives are catalogued in the archive, and includes Linda M. Morra’s chapter, “Autobiographical Text, Archives, and Activism: The Jane Rule Fonds and Her Unpublished Memoir, Taking My Life” and Yuriy Zikratyy’s contribution, “Interviewing Hustlers: Cross-Class Relations, Sexual Self-Documentation, and the Erotics of Queer Archives.”

Together the chapters acknowledge that the archive, much like the closet, exposes various fluctuating levels of visibility and privacy. Coming out of the closet, that metaphor so central to public disclosure of a previously held secret, constitutes sexual and gender identities not only within the speech act itself, but as Eve Kosofsy Sedgwick reminds us, within a web of circulated knowledge. Recognition, awareness, refusal, impulse, disclosure, framing, silence, and cultural intelligibility are each mediated and determined through insider/outsider ways of knowing. These relationships strike a delicate balance between reach/ability and remoteness, between precarity and pleasure. Archival documents, detritus, and objects that are marked as queer in some way beg questions of (il)legibility and sustained attention to archival method, complicating the ways in which archives gather, assemble, display, and (de)legitimize materials relating to sexual and gender identities.

Out of the Closet, Into the Archives draws from and contributes to this queer experience by exploring the complexities of archival research attempting to identify, catalogue, and preserve queer histories. Archival research that utilizes special collections, manuscripts, personal papers, organizational files, and other ephemera is a critical part of constructing LGBTQ history. And yet there is something undeniably queer about LGBTQ archival research. We interrogate the way that this archival research evokes older meanings of the word “queer,” the way experiences in archives can be odd and perplexing, can spoil or ruin an existing understanding of history, and can involve deviations from standard archival protocols.

This volume also uses more contemporary understandings of the word “queer” as it explores how archival research involves serendipity, creativity, and an examination of items beyond the scope of the traditional archive. This creativity is often a response to a long history of LGBTQ life being “hidden from history,” obscured within existing sources or discarded entirely. Indeed, in the attempts of historians to “document the history of homosexual repression and resistance,” many scholars “have recovered a history suppressed almost as rigorously as gay people themselves.” Thus, LGBTQ archival research becomes queer when it becomes part of a process of recovery and justice for a queer past and present—shifting the presence of LGBTQ lives and histories from margin to center.

So why think about the affective experience of queer archives and queer archival collections at all? Accounting for the tactile, bodily experience of being in/at the archive inspires our awareness of queer touches across time, where materials become imminent and perhaps immanent in ways that they are not ordinarily. The peculiarities of archival time and space are inseparable; queer lives, often marked by their ephemeral and nonlinear nature, are contained in archival spaces that are, paradoxically, ordered and opaque. At the heart of this volume lies a desire to engage with the complexities of researchers’ experiences in the archive—exposing readers to the experience of how it feels to do queer archival research and queer research in the archive.

Jaime Cantrell is a Visiting Assistant Professor of English and faculty affiliate at The Sarah Isom Center for Women’s and Gender Studies at The University of Mississippi. She specializes in sexuality studies, Southern Studies, and 20th century American literature. She has articles and reviews appearing in Study the South, Feminist Formations, The Journal of Lesbian Studies, and This Book Is an Action: Feminist Print Culture and Activist Aesthetics. She co-edited Out of the Closet, Into the Archive: Researching Sexual Histories (SUNY Press, Queer Politics and Cultures series, 2015), and is presently at work on a book project titled Southern Sapphisms: Sexuality and Sociality in Literary Productions, 1969-1997.

Jaime Cantrell is a Visiting Assistant Professor of English and faculty affiliate at The Sarah Isom Center for Women’s and Gender Studies at The University of Mississippi. She specializes in sexuality studies, Southern Studies, and 20th century American literature. She has articles and reviews appearing in Study the South, Feminist Formations, The Journal of Lesbian Studies, and This Book Is an Action: Feminist Print Culture and Activist Aesthetics. She co-edited Out of the Closet, Into the Archive: Researching Sexual Histories (SUNY Press, Queer Politics and Cultures series, 2015), and is presently at work on a book project titled Southern Sapphisms: Sexuality and Sociality in Literary Productions, 1969-1997.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Terrific topic with great details….I too have created collections and processed those of others ….the thrills are odd and powerful, starting with the weird allergies from inhaling archival dust, continuing and yes there is boredom and then suddenly, a lucky thrill: the smoking gun that proves your hunch, the cache of fabulous photos, the important souvenirs in the most unusual places.