Lisa Brigandi

“I tightened my legs around her waist, pressing my groin into the space between two shallow dimples framing the small of her back. She picked up the pace …”

This excerpt from “Tom Girl”—a zine held by New York University libraries in the Riot Grrrl Collection—is one of many zines from the Riot Grrrl era that focuses on the sexual awakening of a narrator’s same-sex desires within the bounds of friendship. In the 1990s, many young American women found these relationships confusing, isolating, and difficult to put into words. The Riot Grrrl records recount uncertainty about what this arousal meant for their identity. Writers shared their experiences in zines, showing other young women that they were not alone as their blossoming interest in women awoke through these sexually charged friendships.

As explained in The Archival Turn in Feminism, “the creation of archives has become integral to how knowledges are produced and legitimized and how feminist activists, artists, and scholars make their voices audible.” In this vein, NYU actively collects and accessions materials related to girlhood, sexuality, and same-sex sexual attraction.The Riot Grrrl Collection is an archive of same-sex sexual desire even as the very presence of Riot Grrrl material in the NYU archives legitimates these desires and their historical contexts.

Riot Grrrl is a subset of late 1980s, early 1990s punk rock. Best known for Bikini Kill frontwoman Kathleen Hanna’s famous declaration of “girls to the front,” this musical subculture eked its way into the mainstream by challenging notions of sexism, misogyny, and homophobia. Through their lyrics, art, and activism in, and outside, the punk scene, Riot Grrrl challenged fans and zine writers to express their identities as women, speak about their desires and experiences with sex without shame, and support each other as they wrote and read about what kinds of sex they wanted and with whom they wanted to have it.

NYU’s collection of materials relating to Riot Grrrl contains a wide variety of zines, personal correspondence, video, and photographs. The collection houses material focusing on both heterosexual and homoerotic relationships. Many of the essays, poems, and illustrations center on young women’s personal experiences with the dawning of same-sex sexual desires or fantasies. They explore individuals’ experience of pleasure with a same-sex partner and what repercussions such pleasurable acts had for identity.

In a piece in “Homocore N.Y.C.,” a narrator recalls a situation in which a friend asked her to “practice” kissing. Similarly, the author of “Riot Grrrl NYC #6” described a sexual encounter with a friend, though she “couldn’t tell how she meant it.” For these young women, the line between a best friend that is a girl and a girlfriend was blurry at best.

While this overlap between friend and lover occurs repeatedly throughout the zines, it is most lovingly recorded in “Tom Girl.” Told from the first-person perspective of a girl name Carolyn, “Tom Girl” is a nine-page narrative of Carolyn and her friend Elizabeth, “Lizard,” sneaking off to swim in a nearby lake late at night. They share their disobedience, nudity, and ill-understood adolescent desires, which culminate in a sexual encounter. Starting at the edge of the lake, the friends begin removing their clothes. “‘I have really embarrassing underwear on,’ Elizabeth said a couple of minutes later as she inched up toward the water, dragging her toes through the pebbly sand to slow her movement. Couldn’t tell if she was inviting me to peek or begging me not to look … Lizard reached an arm behind me. Her arm fell on my ass and she held it. That’s when I knew for sure what was happening …” Elizabeth hoists Caroline up on her back but Caroline keeps sliding down: “For the next three million seconds I slid and she hoisted, slid-hoisted, slid-hoisted again and again until my groin started pulsing and my heart stopped.” Caroline drops into the lake and the friends start splashing one another. The meaning of the interaction—friendly or sexual?—remains ambiguous until the last page when Elizabeth dives underwater and surfaces right behind Caroline: “Pressed firmly behind me, Lizard placed her lips on my right ear lobe and paused for ten seconds. Then she half whispered/half growled ‘my turn.’”

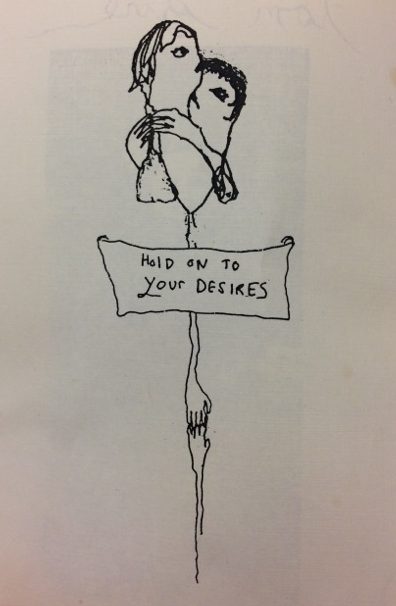

The story is typed and surrounded by minimalistic line drawings of two bodies drawn without lifting the pen; the two are constantly connected. This artistic decision links them in ways that could be physical (two bodies connected in the act of sex), emotional (two people connected in friendship), or both.

Though often trivialized as a phase, experimentation, and even “suburban angst,” the Riot Grrrl movement provided writers with an outlet: personal zines from this social and musical movement showcased the earnest and vulnerable exploration of the authors’ and artists’ sexual desires. In these zines, friendship provided a venue safe enough for readers and writers to push the heteronormative boundaries surrounding adolescence. Authors explored sexual intimacy with other girls in a way that did not force them to make a declaration of their sexual orientation or “come out.” They used the guise of best-friendship to be physical with other girls in ways that parents, peers, and authority figures might have quashed if it had appeared more overtly queer.

The Riot Grrrl Collection serves, in former archivist Lisa Darms’s words, to legitimize and validate the materials as “cultural products” that will minimize “the reductive narrative” surrounding Riot Grrrl and “authorize them as cultural rather than exclusively subcultural” materials.Though several articles on the collection refer to it as nostalgic—implying that its purpose is solely for entertainment value or for reminiscing millennials—Darms contends that the collection is more than that. Darms’s curation of the Riot Grrrl Collection represents the movement as a “queer feminist hybrid of punk, continental philosophy, feminism, and avant-garde literary and art traditions.” It is not a collection for fans per se, but a collection of a movement that drew from both high and low cultures to provide a new path for young women’s sexuality.

Lisa Brigandi is an Access and Resource Sharing Supervisor at Syracuse University Libraries. She has an MLIS from St. John’s University and a BA in English from Le Moyne College. She is interested in collections related to personal experience (letters, journals, zines), local histories, and religious relics.

Lisa Brigandi is an Access and Resource Sharing Supervisor at Syracuse University Libraries. She has an MLIS from St. John’s University and a BA in English from Le Moyne College. She is interested in collections related to personal experience (letters, journals, zines), local histories, and religious relics.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com