In the 1662 version of Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives, English physician Nicholas Culpeper wrote on the ‘wanton’ practices of virgins. Discussing whether the hymen could be a ‘sign of virginity’ in maidens, Culpeper argued that there was something like a membrane that is ‘violated in first copulation’, but that: ‘Moreover, this is not to be found in all Virgins, because some are very lustful, and when it itcheth, they put in their finger or some other thing, and break the membrane …’ When Culpeper turned to discussing whether ‘honest virgins’ bled upon losing their virginity, he argued that if virgins did not bleed, ‘they are not be censured as unchast’, for; ‘If the girl was wanton afore, and by long handling, hath dilated the part or broke it, there is no blood after copulation.’

What can we make of Culpeper’s seemingly nonchalant description of the sexual practices of virgins, before marriage or before sexual relations with their husbands-to-be? While historians have long searched the past for traces of the sexual practices, behaviours, and taboos of early modern peoples, masturbation is curiously absent from most studies. Thomas Laqueur’s detailed and thorough cultural history from antiquity to the twentieth century, Solitary Sex (2003), is one of the few works dedicated to analysing solo sex throughout time. Yet, Laqueur notes of the early modern period that authors were largely silent ‘on the subject of solitary sex’. He suggests that most references to masturbation described adult males and the sin of spilling seed, while women were rarely discussed, and if they were, it was in relation to the medical tradition of massaging women’s genitals to cure various ailments.

Is female masturbation thus unrecoverable, unrecorded, or undiscussed in the early modern period, as Laqueur suggests? Are the problems of historical evidence of women’s masturbation the reason for its absence in historical studies? Reading Culpeper’s passages raised these questions for me, but it is also became clear that Culpeper explicitly described some kind of female masturbation. I am thus interested in rethinking and re-examining early modern women’s masturbation, as a historical site of evidential gaps and uncertainties, and as an act or series of acts that have largely been overlooked in historical accounts of early modern sexuality. By rethinking the history of women’s masturbation in this time, we can begin to formulate a clearer understanding of how women may have approached and performed their individual sexual desires, as well as a better idea of how society viewed these sexual desires and women’s acting upon them. Through examining medical, midwifery texts and their authors, we can glimpse the ways in which they captured social ideas about women’s masturbation, and how this informed the ways they presented female desire and masturbation to their readership, who were largely midwives and lay women.

Turning to early modern England generally, chastity was expected of women throughout their lives, and sexual relations were deemed appropriate within the heterosexual paradigms and limits of marriage and procreation. Yet despite the pervasiveness of the expectation of chastity, women, particularly unmarried women like virgins or widows, were frequently portrayed both in medicine and culture as inclined to, partaking in, and even enjoying lustful behaviour. Within the predominant medical understanding of bodies, a woman’s unwed status meant that she could not dispose of excess female seed through the moral releases of marital sex. A build up of this seed was believed to cause bodily ailments, like ‘madness of the womb’, a kind of lustful fervour or insanity.

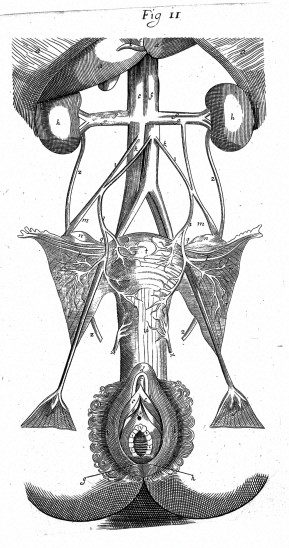

Considering this backdrop, can we therefore understand Culpeper’s descriptions above as some kind of masturbatory act? When Culpeper refers to the ‘itch of the virgin,’ he is likely referring to a feeling of lust, or sexual desire needing to be scratched. Acting on this itch, in his estimations, involved the insertion of fingers and ‘other objects’ into vaginas, as well as ‘handlings’, whatever this may be. Culpeper’s knowledge of these acts, likely obtained through his experiences as a physician and through acquisition of midwives’ knowledge, was also influenced by the canon of early modern medical thought. Women’s sexual organs were largely understood in medical and midwifery knowledge as mechanisms for both conception and women’s sexual pleasure; in this period, most medical traditions held that women needed to orgasm in order to conceive. As the midwife Jane Sharp described in The Midwives Book (1671), specifically of the clitoris;

So by the stirring of the clitoris the imagination causeth the vessels to cast out that seed that lyeth deep in the body, for in this and the ligaments that are fastned in it, lies the chief pleasure of loves delight in Copulation; and indeed, were not the pleasure transcendently ravishing us, a man or woman would hardly ever die for love.

The clitoris has historically been subject to a range of interpretations by medical authority, yet in Sharp’s account, sexual pleasure specifically arising from the clitoris was not something discouraged or unspoken, but discussed openly here in a text written by a woman, for women.

Despite this, the question of women’s desires could still attract the concern of medical authors, which possibly reflected a social concern regarding unmarried women’s solo sexual practices. One particularly insightful example of this is Scottish physician James MacMath’s The Expert Mid-Wife (1694).

MacMath begins his treatise, specifically aimed at lay-women and midwives, with a somewhat apologetic preface, explaining that he has ‘omitted a description of the parts in a woman destined to generation’, like the clitoris, ‘lest it might seem execrable to the more chast and shamefast, through baudiness and impurity of words’. He does this, he states, to prevent the reader from discovering ‘debauchery’ or the ways to sinfully ‘abuse’ women’s parts. Yet, merely twenty pages further on, MacMath describes how:

… lascivious virgins, and widows, wholly intent to lustful cogitations, and much in thinking of breasts, milks, and their sucking, wantonly rubbing, tickling, and their sucking thereof, may have got milk in them.

MacMath here refers to both physical and imaginary masturbatory practices of unwed women, which could cause the development of a kind of breast ‘milk’ in women who were not pregnant. The description of these kinds of lustful practices becomes much more explicit in MacMath’s later discussion on false conceptions—also referred to in the early modern period as moles—which were typically masses of flesh engendered in women’s wombs that caused the same signs as pregnancy. Early modern physicians like MacMath believed that these false conceptions could be created by the sexual imagination and possible masturbation of a woman alone. As MacMath described, this occurred in ‘widows and virgins (the more salacious or lustful chiefly) and merely from a fancied or imaginary venery, without knowing Man’. These women could, through ‘lascivious converse, or then by venerous dreams, as to some singular delectation’ create this false conception through causing their own seed to be ejaculated or collected in the womb.

How then, can we interpret MacMath’s descriptions, particularly in the face of his refusal to describe the ‘parts’ used for generation, and his warnings against the ‘sinful’ use of women’s bodies? While he begins his guide for midwives and women with these declarations, MacMath is explicit about the sexual acts of women alone. He perceived virgins and widows as participating in lustful or ‘wanton’ acts involving their bodies, specifically the ‘rubbing’ and ‘tickling’ of their breasts, and as participating in ‘imaginary’ acts of ‘venery’ which caused women to orgasm or ejaculate their seed. Importantly, throughout his discussion of these acts, he does not chastise women who may engage in such behaviour, with the exception of his description of them as ‘lascivious’ or ‘salacious’. This could possibly indicate an acceptance of such behaviour, or the frequency of its occurrence, and while such descriptions are presented through the lens of MacMath’s medical and masculine gaze, they have been written in a text whose intended audience—women and midwives—would likely have recognised these behaviours.

In considering MacMath’s, and other medical or midwifery texts, I want to encourage historians to begin rethinking early modern women’s masturbation as an area of the history of sexuality, and an area of women’s history, that is lacking. While it has traditionally been thought that women’s masturbation is absent from the archives, or that early modern authors were not discussing the topic, it is clear from the above examples that it was discussed, and that it was seemingly acceptable behaviour for unmarried women to engage in. That Culpeper encouraged his readers not to ‘censure’ maidens as unchaste for ‘handling’ their bodies, and that MacMath explicitly and openly described sexual practices is significant, and I think, offers a place for further analysis of early modern women’s masturbation. In doing this, we can begin to form a broader and more complete understanding of women’s sexuality in the past, and I hope, open up a productive dialogue between past and present representations and practices of women’s masturbation.

Paige Donaghy is a recent Honours graduate in History from the School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry and the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland, Australia. Her thesis examined early modern European medicine and science. She is currently interested in the history of early modern women’s sexuality, and the relationships between sixteenth- and seventeenth-century medical and cultural concepts of masturbation, imagination, and self-generation.

Paige Donaghy is a recent Honours graduate in History from the School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry and the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland, Australia. Her thesis examined early modern European medicine and science. She is currently interested in the history of early modern women’s sexuality, and the relationships between sixteenth- and seventeenth-century medical and cultural concepts of masturbation, imagination, and self-generation.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

What seems to be missing from discussions of this topic is the relationship between menstruation and masturbation. Today it is commonly recognized that menstrual cramps can be relieved somewhat by orgasm, no matter how achieved, and surely many women of the Early Modern Era (and all other eras as well!) discovered this “treatment.” To fully understand women’s masturbation practices in any era one needs to include an examination of attitudes and behaviors related to the menstrual cycle.