Recently, while researching the history of wives who desired women in the post-WWII United States, I came across two of the most dramatically defaced library books I have ever encountered: Gilbert D. Bartell’s Group Sex: A Scientist’s Eyewitness Report on the American Way of Swinging (1971), and Elizabeth Reba Weise’s edited collection Closer to Home: Bisexuality & Feminism (1992). It is perhaps coincidental that both of these texts deal primarily or significantly with female bisexuality, but the ways in which these books were damaged—so as to make the simple act of reading about bisexual women’s lives more difficult—serve as an apt metaphor for the obstacles that exist in charting the history of female bisexuality in the modern United States. Central among these obstacles is the extent to which bisexual-identified women have been dismissed as either “truly” heterosexual or “truly” lesbian.

In the copy of Group Sex I took out from the University of Texas at Austin Libraries, eight pages had been carefully sliced out of the middle of the book. Coming across these missing pages as a reader was disconcerting. Significantly for my research purposes, and clearly for those of the offending reader, this extracted section of the Group Sex describes in detail the ways in which swinging husbands encouraged their wives to engage in sex with other women, often while they participated indirectly as voyeurs. Perhaps the reader who cut out these pages did so because he or she found them morally repugnant, though in that case, it seems odd that the rest of the text was untouched. Or perhaps the reader needed these pages for his or her research, much as I did, but was simply too lazy to take notes. The possibilities are multiple, but my immediate suspicion was that the offending reader found these pages particularly titillating, and wanted to extract them as fodder for future fantasizing but was too embarrassed to take them to the photocopier. An insert in Group Sex, placed there by a librarian in August of 1995, evocatively describes the book as being “mutilated.”

In the copy of Group Sex I took out from the University of Texas at Austin Libraries, eight pages had been carefully sliced out of the middle of the book. Coming across these missing pages as a reader was disconcerting. Significantly for my research purposes, and clearly for those of the offending reader, this extracted section of the Group Sex describes in detail the ways in which swinging husbands encouraged their wives to engage in sex with other women, often while they participated indirectly as voyeurs. Perhaps the reader who cut out these pages did so because he or she found them morally repugnant, though in that case, it seems odd that the rest of the text was untouched. Or perhaps the reader needed these pages for his or her research, much as I did, but was simply too lazy to take notes. The possibilities are multiple, but my immediate suspicion was that the offending reader found these pages particularly titillating, and wanted to extract them as fodder for future fantasizing but was too embarrassed to take them to the photocopier. An insert in Group Sex, placed there by a librarian in August of 1995, evocatively describes the book as being “mutilated.”

Group Sex was part of a burgeoning, interdisciplinary field of research in the 1970s on “alternative lifestyles” which included “swinging” or “wife-swapping” as it was more derogatorily called. Bartell and other scholars who were drawn to this topic in the 1970s—including George and Nena O’Neill, James W. Ramey, and Brian Gilmartin, among others—were particularly interested in why and how this sexually “deviant” phenomenon had emerged among otherwise “normal,” white, middle-class, middle-aged suburban married couples, and the ubiquity of sex between women at swinging events and parties was something that nearly all researchers on swinging noted with surprise. While sex between men at swinging parties was generally verboten, scholars estimated that the number of swinging women who engaged in same-sex acts ranged from 60 to 100 percent. Rather than taking such women’s widespread participation in lesbian sex as evidence of women’s own desires, however, most researchers believed that swinging wives engaged in sex with other women in an attempt to please their husbands or to provide visual stimulation to help swinging men “recycle” more quickly after orgasm.

There is, without doubt, some truth to such arguments: men did frequently act as spectators while their wives engaged in lesbian sex at swinging parties. But the idea that wives engaged in lesbian sex solely in order to please their husbands contradicted such women’s own testimony (the wives in Bartell’s study repeatedly told him, much to his consternation, that they engaged in sex with women because they “enjoyed it”) and reflected researchers’ biases. Namely, their inability to understand why otherwise “normal” married women would engage in same-sex acts, if not for the benefit of the men in their lives. Thus, while most scholars described swinging women as actively “bisexual,” the emphasis they placed on women’s over-riding desires to sexually pleasure and stimulate their husbands, suggested that they remained fundamentally heterosexual.

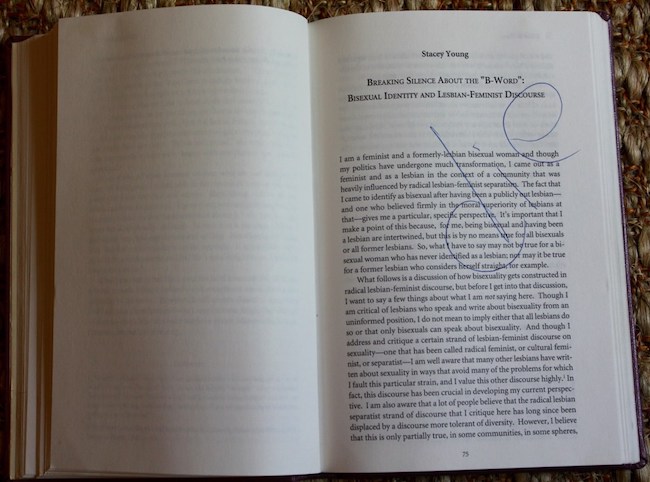

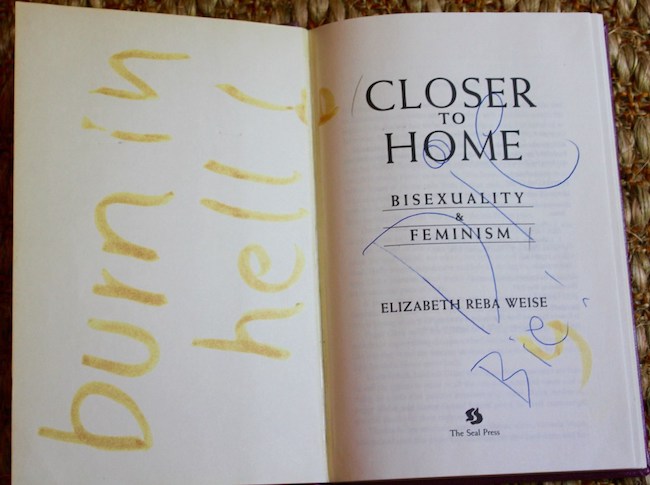

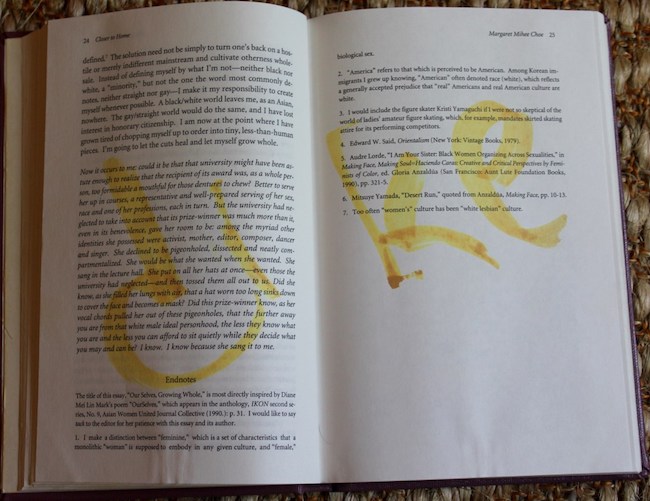

If the otherwise conventional bisexual wives and mothers of Bartell’s study have been widely understood as “truly” straight, more politically active bisexual feminists, like those whose writing appears in Weise’s collection, Closer to Home, have often been seen as “truly” lesbian. This tendency is quite apparent in the UT Austin Libraries’ copy of Closer to Home, in which someone has scrawled catchy phrases including “burn in hell!” and the creatively-spelled “Die Bie!” in pen and yellow highlighter across multiple pages. No library documentation exists to date the graffiti, which suggests to me that it took place only recently. The word “dyke” (also spelled “dike”) appears eight times across the text of the book, but it is the word “die” alone that appears most often. Flipping through the book’s pages, the graffiti creates an incantation of sorts, which reads something like this: die, die, die, die, die, dike, die, dyke, dyke, die. Whether this message was intended for the bi/dykes within the book, the bi/dykes reading the book, or both is unclear, but as a reader the menacing message felt personal, and I was unable to focus on the text of Closer to Home despite it.

That this vandal saw no difference between bisexual and lesbian identity is notable, but hardly unique. While the reader who defaced this copy of Closer to Home was clearly morally opposed to homosexuality, gay and lesbian activists have similarly undermined the stability of bisexual identity. In her introduction to the book, for example, Weise writes that gay and lesbian activists often accuse bisexuals of being “unwilling to face the stigma of homosexuality” or at a stage in the process of coming to a “true” gay or lesbian identity. Lesbian feminists in particular, Weise notes, have been critical of bisexual women who seem to them insufficiently committed to other women and to overturning homosexual oppression. Indeed, since the 1990s, many scholars and activists working within and outside of academia, including Robyn Ochs, Loraine Hutchens and Lani Ka’ahumanu, Paula Rust, Marjorie Garber, and Clare Hemmings, have sought to push back against this understanding of bisexuality.

But while activists, theorists, and sociologists have brought greater academic attention to bisexuality and to bisexual women’s lives specifically, writing about the history of female bisexuality remains sparse. This is surely an effect of a range of causes, from the greater interest and funding available for gathering and preserving “gay and lesbian” histories, and the continuing subordination of bisexual politics within the LGBTQ movement, to the extent to which lesbian-identified women tend to minimize their own cross-sexual desires and experiences in telling their life stories, as historian Amanda Littauer has recently pointed out. Such challenges are evident in my own writing about wives who desired women from 1945 to the present. Most of the women whose stories I have gathered from archival and oral history collections ultimately left their marriages in the 1970s and 1980s and identified as lesbian rather than bisexual, but their lives are also part of the history of female bisexuality, even though they themselves often quite forcefully rejected the term.

Despite these challenges, the copies of Group Sex and Closer to Home I recently encountered suggest that even in these queer times, female bisexuality continues to generate both particularly intense anger and fetishization. The evolution of female bisexuality as an identity category and a social practice, as well the dramatic responses it elicits, demands greater historical attention.

Lauren Gutterman is an Assistant Professor in the American Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin. She co-hosts the podcast Sexing History. Lauren holds a PhD in History from New York University and recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship in the Society of Fellows at the University of Michigan. She is currently revising a book manuscript, Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire within Marriage, which examines the personal experiences and public representation of wives who desired women in the United States since 1945.

Lauren Gutterman is an Assistant Professor in the American Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin. She co-hosts the podcast Sexing History. Lauren holds a PhD in History from New York University and recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship in the Society of Fellows at the University of Michigan. She is currently revising a book manuscript, Her Neighbor’s Wife: A History of Lesbian Desire within Marriage, which examines the personal experiences and public representation of wives who desired women in the United States since 1945.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Thanks for this post – I think! I I find this truly alarming, even while I remember the off-the-scale levels of biphobia that used to exist (also in the UK, where I am from). In particular, it is chilling that presumably two different people with very different interests saw fit to deface both those books.

It seems to me – as someone who came out as bi in the 70s, knew a lot of lesbian separatists in the 80s, and in the late 80s started researching women and bisexuality – that some in-depth history of bisexuality is just begging to be written.