Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci

Contraceptive Diplomacy follows the development of ideas and technologies of birth control in the context of imperial struggles between the United States and Japan. It reveals how a transnational birth control movement developed as the matter of reproduction became intricately tied to race improvement, national prosperity, and world hegemony. While it was feminists and social reformers—led by Margaret Sanger and her Japanese counterpart, Ishimoto Shizue—who initiated the birth control campaigns, they also attracted the interest of various social actors with different political and personal agenda, including eugenicists, socialists, philanthropists, public health officials, social scientists, and biologists. In short, national and international politics played a crucial part in the development of birth control in the mid-twentieth century. While women—both feminist leaders and public figures—were essential parts of the birth control movement, male policymakers and scientists often neglected women’s own voices and agency; as a result, national birth control campaigns often downplayed—or even deliberately excluded—the issues of women’s reproductive rights and female sexuality.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic?

ATD: I have always been interested in people who formed bridges between different cultures, nations, and races—that’s how I became interested in Margaret Sanger’s work abroad, especially in Asia. When I was trying to figure out what led Sanger to Japan in the early 1920s, I eventually discovered that she met some Japanese socialists in New York City, who later invited her to give a lecture tour in Japan. Who were these Japanese socialists and why were they interested in Sanger’s cause? Many liberals and socialists in Japan at the time were seeking for solutions to social problems facing the country as a result of rapid industrialization, including overpopulation, poverty, food shortages, and riots. They were inspired by the Russian Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and as a stepping stone to Moscow, some young Japanese socialists, including Ishimoto Shizue’s husband, headed to New York, where there was a lively, multi-national socialist community. Sanger was part of this community. These socialists saw birth control as a key to give power to laborers, who were suffering from exploitation of both productive and reproductive labor. It was truly exciting, as a historian and researcher, to discover how various events and people across the world came together, forming a historical narrative in unexpected ways. I was also fascinated by the mobility of these activists from a century ago—although limited to those with relatively substantial means—who crossed national borders to find creative ways to extend their cause when domestic politics thwarted their efforts.

NOTCHES: Other than the history of sex and sexuality, what themes does your book speak to?

ATD: Reproductive issues, which essentially involve people’s sexual behaviors and activities, are not just a personal matter, but also a national and even global concern, as they determine the size and quality of the population. The birth control movement therefore represented various intellectual trends, political ideologies, and social movements of the time, including the women’s movement, eugenics (i.e. ideas of race improvement), public health initiatives, socialism, nationalism, and anti-communism. Many of these movements and ideologies operated on a global level and transcended national borders.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book and were there any especially exciting discoveries?

ATD: I did half of my research in US archives and libraries and half in Japan. Sometimes the most interesting discoveries came from most obscure and unexpected places. I was especially excited when I came across a small book at a used bookstore right near my parent’s house in Tokyo; it was a personal memoir written by a Japanese public health official, who I feature in my book, with his original signature and inscription. The memoir included the author’s travel account of his 1950 trip to the United States, funded by the US government, to study public health/birth control programs in Southern states. This piece not only provided a personal perspective to the story of birth control in postwar, US-Occupied Japan, but it also revealed how US racial politics translated into Japanese reproductive policies, specifically through birth control programs in rural areas. (You can find my essay on this topic here.)

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

ATD: One of the fascinating figures in the story of the early birth control movement in Japan was a labor activist and biologist called Yamamoto Senji. He served as a translator for Sanger’s lectures in Japan during her first visit there in 1922. He left some interesting observations about Sanger (read my book for details!), and later led the proletarian-based birth control movement in Japan. The more I delved into his personal background, the more fascinated I became about this figure; but I couldn’t include all the details in my book—only his role in the birth control movement, which is only part of his multifaceted lifework. He studied in Canada as a youth, at some point became inspired by socialist thoughts, and later became a biology professor at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Yamamoto strove to spread knowledge about the human body, especially human sexuality, to the masses. For that reason, he was deeply inspired by Sanger’s work and shared her mission (at least during her earlier years) of spreading the knowledge of sexuality beyond exclusive medical circles. He offered some sexology classes to university students as well as to laborers. He later became a representative of the Labor-Farmer Party in Japan, aspiring to bring power to laborers, but was stabbed to death by a right-wing extremist at the age of 41. Maybe I can write an article about his work on sexology in the future.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

ATD: I have always centered my focus on Margaret Sanger and Ishimoto Shizue. However, at the beginning of my research, I only saw these figures as a starting point of my study on the history of birth control and eugenics in the context of US-Japan relations. While I still feature many other actors who were involved in the transnational birth control movement, I did not expect that these two women would remain so influential for all the decades that my work covers—from the 1920s to the 1950s. In particular, Sanger’s pill project in the 1950s—the crucial role that she and her Japanese and American collaborators played in its development—was a story that I started to expand during the later stages of my research.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

ATD: I’ve been fascinated by the history of sexuality, especially as it relates to the issue of reproduction, because it is fundamental to human history itself. There are both biological and social components to the matters of sexuality and reproduction, which require us to see these issues from multidisciplinary and transnational standpoints. From its history, we can learn about the intellectual trajectories and power struggles over how people have defined gender, race, nation, and ultimately what it means to be human.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

ATD: I think my book will work well with other works that look at issues of female reproduction and sexuality in a transnational/global framework, e.g. Laura Briggs’s Reproducing Empire, Matthew Connelly’s Fatal Misconception, etc. I’d also like it to be used alongside other scholarship on the history of sexuality in Asia—a relatively unexplored field, I believe, at least in the English-language scholarship.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

ATD: With increasing interaction and flow of people, information, and materials across national borders in the era of globalization, I believe that a transnational perspective is vital to understanding various social issues and phenomena. Transnational influences have been used, not solely for progressive goals or in liberal directions, but often for nationalist purposes as well.

Both in Japan and the US, many politicians and pundits are alarmed by the declining fertility of its “core” (or, “white” in the US) population. The fear of low birth rates, I believe, has led to stricter restrictions on abortion and birth control in the US, Japan and many countries in the world. Women—whether it’s their sexuality, or their “selfish” aspiration for a career in the work place—have been blamed for bringing down the nation or the race. However, as past and current cases in many countries have suggested, top-down policies restricting women’s rights and choices do not increase birth rates, especially in the long run.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

ATD: My next goal is to translate my book into Japanese. There continues to be a sharp divide between American studies and East Asian studies, and much of this has to do with the language issue. I would especially want the Japanese general public to know about this history of reproduction during the turbulent decades in Japanese history, as many of the topics remain highly relevant today. For example, in order to deal with the issue of low fertility in Japan, a trend that many politicians are struggling to reverse, it’s important to look back into history to understand how reproductive issues have appeared in national/transnational discourses and how women have taken part in and responded to these discourses. Additionally, over the past year, there’s been a rise in national attention to the cases of forced sterilization performed under a law that passed during the US Occupation of Japan (Eugenic Protection Law). I cover the background and discussions surrounding this law—how reproductive control, including (semi-forced) sterilization, was seen as a key to Japan’s racial and national recovery after World War II. This knowledge, I believe, would be helpful in understanding the politics of reproduction today, which have been shaped by events, laws, and movements from over half-a-century ago.

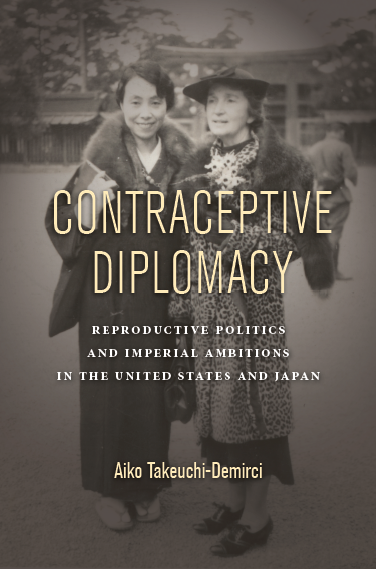

Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci (American Studies, Brown University, Ph.D.) is Assistant Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of Koç University Center for Asian Studies. She is author of award-winning book, Contraceptive Diplomacy: Reproductive Politics and Imperial Ambitions in the United States and Japan (Stanford University Press, 2018).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com