Amber R. Clifford-Napoleone

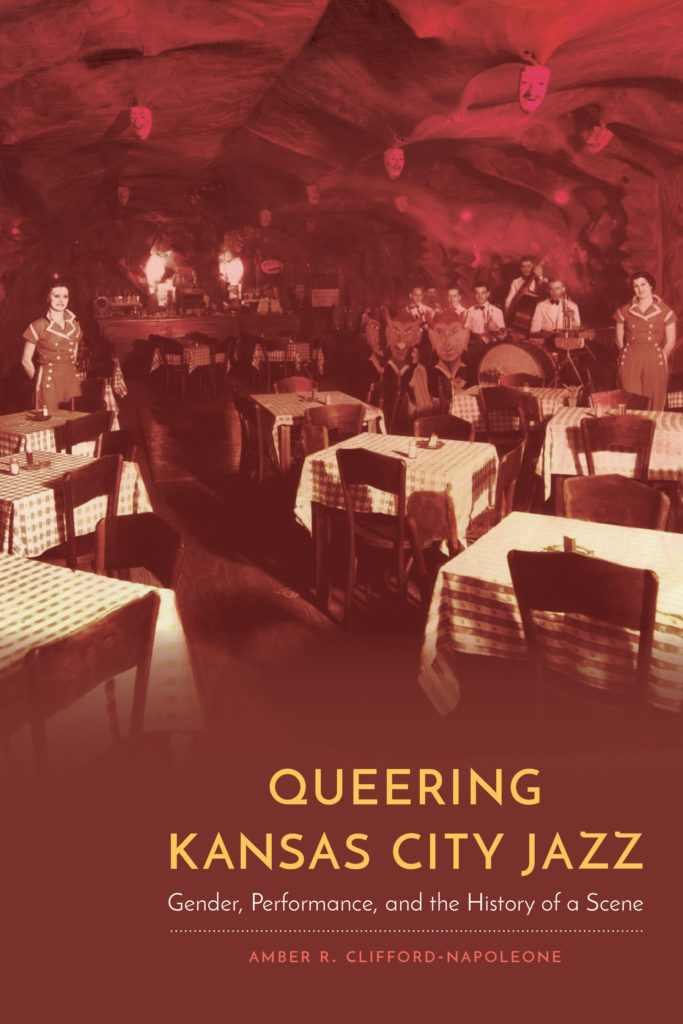

Queering Kansas City Jazz: Gender, Performance, and the History of a Scene is about Kansas City and its jazz scene, especially its peak years in the 1920s and 1930s, but not in the way readers expect. It is not about music. It is a study of forgotten performers and gender benders, the people we tend to forget: table singers, background players, drag performers and theater acts who were never famous. Queering Kansas City Jazz uncovers a hidden and forgotten aspect of the city’s jazz scene with the stories of people experimenting with gender, sexuality, and identity.

NOTCHES: What drew you to this topic, and what are the questions you still have?

Clifford-Napoleone: Initially, it was an advisor who led me to Kansas City jazz. Arthur McClure, a professor of history at the University of Central Missouri and one of my mentors, would tell me stories about sneaking into jazz clubs as a teenager in the city. Then I began to wonder how I, a lesbian and a white woman, would have fit in those times and spaces. It’s a project I worked on for a long time, including through my dissertation. I’m still interested in the same questions because I think there is so much more to say about the people who made the jazz scene possible. We hear too often about the “Paris of the Plains” and not enough about the working women, and the people of color, who made that scene possible.

NOTCHES: This book is about the history of sex and sexuality, but what other themes does it speak to?

Clifford-Napoleone: It speaks quite a bit to performance, not just performance of jazz musicians and singers, but also the performance of gender identity across sections of the city. It also speaks directly to the historiography of Kansas City jazz and suggests that other works on the topic all fall within a particular silo of thinking about the city and its place in American jazz history.

NOTCHES: How did you research the book and what sources did you use? Were there any especially exciting discoveries, or any particular challenges?

Clifford-Napoleone: My most exciting discovery was complete happenstance. I was working on my PhD at University of Kansas (KU), going through secondary source material in jazz history and working through oral histories collection as part of the Goin’ To Kansas City Collection, which is housed at Rutgers and at University of Missouri-Kansas City. My advisor Sherrie Tucker told me that a new collection was accepted at KU’s Spencer Library and that they needed a volunteer to catalog it and write a finding aid, something I had experience with. That led me to Edna Mae Jacobs, a long time performer and club owner in Kansas City, and her scrapbooks on drag performance in Kansas City jazz. I went on to research at Rutgers, in New York and Connecticut, to dozens of interviews and time spent with newspapers, maps, and old telephone books.

NOTCHES: Whose stories or what topics were left out of your book and why? What would you include had you been able to?

Clifford-Napoleone: I did not spend much time on jazz music itself. I know that many other historians and scholars have written excellent volumes on jazz music history, but for me the music was a backdrop for the people and events of Kansas City. I wanted to tell a different story. As for what I would have included if I had been able, the fact is that the people I want to talk about didn’t leave records and they are seldom remembered. How much do we actually know about the hundreds of table singers, the prostitutes, and itinerant populations on and off the train? Had I been able to I would have focused on more of those stories.

NOTCHES: Did the book shift significantly from the time you first conceptualized it?

Clifford-Napoleone: It did. I had originally planned a work more focused on public amusements, on the clubs themselves. I was interested in a working-class history of Kansas City jazz, but I was coming out at the same time. In the end, I shifted toward a look that was more focused on gender identity and sexuality, and more on performers than performance spaces.

NOTCHES: How did you become interested in the history of sexuality?

Clifford-Napoleone: I read Foucault. My education coincided with the growth in the 1990s of postmodern and queer theory, and the first time I read Foucault’s History of Sexuality volume I it completely changed the way I looked at everything. I love theory, both reading it and teaching it, and I read everything I could about theories of sexuality in the 1990s. I also read everything Esther Newton had written to that time and came to deeply appreciate how theories build over time; they are not the product of one scholar. Histories of sexuality work that way too: just because it seems new and sounds new, does not mean that it is a recent innovation.

NOTCHES: How do you see your book being most effectively used in the classroom? What would you assign it with?

Clifford-Napoleone: We live in a pop culture moment in which RuPaul’s Drag Race wins awards and trans children come out earlier and earlier. Inside the classroom, however, we really need to catch up. Students in specific disciplines get a lot of classroom discussion time around sexuality, but for most students that opportunity only comes in general education classes. While I know many historians who do teach LGBTQ+ history in their classes, just as many are afraid or confused about how to do that. I think that, too often, LGBTQ+ history in our classrooms gets boiled down to Stonewall, as if queer people only appeared in the 1960s. I’d like to see my book used as a way to help students understand that queer people have always been here, in the Midwest, working for a living, and give them an opportunity to then consider how drag became problematic. I’d assign it with a recording of Lucille Bogan’s “B.D.Woman’s Blues,” an episode of Drag Race All-Stars, and a good bit of Langston Hughes poetry.

NOTCHES: Why does this history matter today?

Clifford-Napoleone: It is so easy to allow a particular narrative to tell your story, even if that narrative is not complete, or nuanced, or even the truth. The narrative of Kansas City jazz is pretty glorious: trains and clubs and famous musicians rubbing elbows and playing until dawn. It’s a narrative that the city has embraced as its place in history. Like all cultures and histories, however, there is never a singular perspective, there is never one story. Kansas City jazz was a product of multitudes, and it was never a music, it was a place and a space where life could be experimental, whether that experiment was Charlie Parker’s music or Edna Jacobs’ cross-dressing. If we want our younger generations to understand and appreciate history, they must be able to see some aspect of their own lives in the lives of those before them.

NOTCHES: Your book is published, what next?

Clifford-Napoleone: I’m playing with a lot of projects right now. I’m working on a long-term project on the history of Anthropology with my colleague Jeff Yelton, and I’m doing the preliminary work for a project that looks at the intersection of fetish, popular culture, and industrial music. Finally, I have a couple of bands and performers that need their stories told, and that is always on my mind. Meanwhile, I teach every day and value my teaching time above everything except my family.

Amber R. Clifford-Napoleone is an anthropologist, an ethnomusicologist and a museum scientist who is currently Professor of Anthropology at the University of Central Missouri. She is also Director of the McClure Archives and University Museum, an ethnographic museum and the university’s official repository. Clifford-Napoleone works primarily in the areas of material culture and textiles as a museum scientist, but her research interests are non-normative gender and sexual identity and its intersections with popular music. Her first book, Queerness In Heavy Metal: Metal Bent (Routledge, 2015) was an ethnographic study of self-identified LGBTQ+ heavy metal fans. She is currently interested in forms of industrial, post-industrial, and experimental sound and its role in creating inclusive communities.

Amber R. Clifford-Napoleone is an anthropologist, an ethnomusicologist and a museum scientist who is currently Professor of Anthropology at the University of Central Missouri. She is also Director of the McClure Archives and University Museum, an ethnographic museum and the university’s official repository. Clifford-Napoleone works primarily in the areas of material culture and textiles as a museum scientist, but her research interests are non-normative gender and sexual identity and its intersections with popular music. Her first book, Queerness In Heavy Metal: Metal Bent (Routledge, 2015) was an ethnographic study of self-identified LGBTQ+ heavy metal fans. She is currently interested in forms of industrial, post-industrial, and experimental sound and its role in creating inclusive communities.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com