Gareth Smith

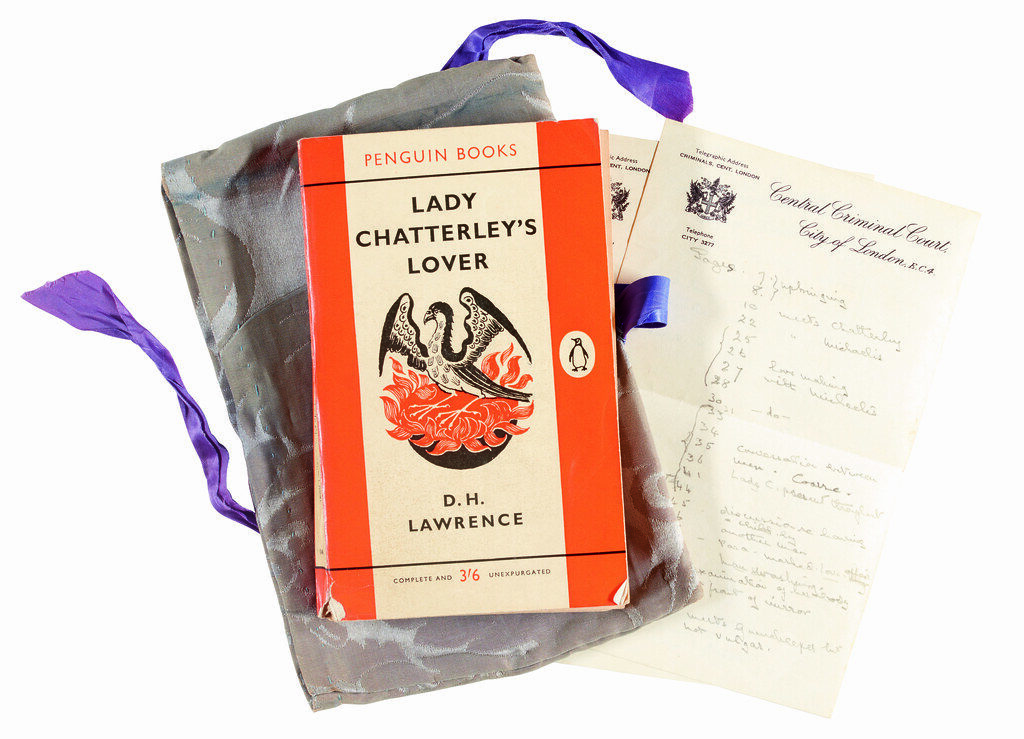

On November 2, 1960, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) was found ‘not guilty’ of obscenity charges at the Old Bailey, permitting the publication of a sexually explicit novel that had been banned for decades. Thus the story of the adulterous affair between Lady Connie Chatterley and her gamekeeper Oliver Mellors became available to millions of British readers and was accompanied by extensive media coverage. The trial is often credited with historical, social and cultural significance far beyond an individual court case, as testified by the almost obligatory presence of Philip Larkin’s poem ‘Annus Mirabilis’ (1967) in essays and articles on the subject: ‘Sexual Intercourse began / (which was rather late for me) – / Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban / And the Beatles’ first LP’.

Larkin’s positioning of the trial as a measure of Britain’s changing attitudes to sex and sexuality has been both echoed and challenged over the last sixty years, but this debate often ignores an element that is long overdue critical attention. The Chatterley trial hinged on the disavowing or defending of ‘deviant’ sexual acts within the novel, reflecting and amplifying broader post-war anxieties about normative sexuality. When viewed from this perspective, it becomes a distinctly queer case.

The accepted narrative of the trial has been that of a liberal Defence pitted against a reactionary Prosecution, but in fact both sides offered conservative interpretations of the novel’s sexual content. The Prosecution identified adultery as the source of the novel’s obscenity, with Sybille Bedford’s articles for Esquire and C.H. Rolph’s commentary in the official Penguin account stating that it was as though Lady Chatterley herself were on trial. Rather than challenge this conflation of literary obscenity with moral judgement, the Defence reversed the terms of the argument by suggesting that Lawrence was condemning adultery and revering monogamy. Their barrister Gerald Gardiner stated that,

It is quite plain, in my submission, from the whole of this book that the author is pointing out that promiscuity yields no satisfaction to anyone and that the only right relationship is one between two people in love which is intended to be a permanent one.

This determination of the Defence to present the novel as conforming to normative sexual conventions was closely connected to the historical context of the trial.

The proximity of the case to the Wolfenden Report offers a partial explanation for this preoccupation with policing sexual propriety. The report, produced by a Home Office departmental committee, focused on legal reform in the areas of prostitution and homosexuality and attracted widespread publicity upon publication in 1957. It responded and contributed to a growing focus on sexuality in British culture which Prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones alluded to when telling the jury, ‘you have only to read your papers to see, day by day, the results of unbridled sex’. The Defence attempted to ensure that their interpretations of the text disavowed any suggestion of sexual nonconformity. Hector Hetherington, editor of the Guardian, gave testimony that contrasted the ‘literary merit’ of Lady Chatterley’s Lover with ‘books on sale openly dealing with sadism, lesbianism, incest, sexual perversions’.

Despite these protestations, there were moments during the trial which suggested that the novel depicted more subversive sexual acts. Doris Lessing acknowledged that Lady Chatterley’s Lover contained a description of anal sex but claimed that ‘it was not noticed by judge or jury, by the prosecution or defence – not by anybody’. However, this was noted by numerous commentators – including those present in court. During the closing remarks, the Prosecution read from the scene identified by Lessing:

It was a night of sensual passion, in which she was a little startled and almost unwilling: yet it pierced again with piercing thrills of sensuality, different, sharper, more terrible than the thrills of tenderness, but, at the moment, more desirable. Though a little frightened, she let him have his way…

C.H. Rolph stated that Prosecutor Griffith-Jones then added, ‘[n]ot very easy, sometimes, not very easy, you know, to know what in fact he is driving at in that passage’ and that ‘[t]his unexpected and totally unheralded innuendo visibly shocked some members of the Jury’. This reaction suggests an awareness within the courtroom that the scene could be read as depicting anal sex. This interpretation circulated further and with greater emphasis after the trial itself had concluded.

The literary periodical Encounter became the primary channel through which a debate about the presence and significance of anal sex in the novel continued. Numerous writers and correspondents engaged with the topic through essays, articles and letters that continued over multiple issues and several years. It began with Andrew Shonfield’s article ‘Lawrence’s Other Censor’ which, with reference to the court case, analysed the scene in question and concluded that ‘we are left in no doubt that what Mellors did was unconventional and even perverse’. In the ensuing discussion, the potential link between depictions of anal sex and queer sexualities was often refuted. John Sparrow argued in a 1962 issue of Encounter that it was not ‘to be equated (as is sometimes ignorantly supposed, and as colloquial usage might suggest) with homosexual practice’, but even the act of disavowal created a space in which further debates could circulate. In the following issue, the bisexual writer Colin MacInnes responded to Sparrow’s article in order to link the trial to ongoing debates about sexuality. He bemoaned the rigidity of contemporary sexual discourse and ‘[o]ur whole sterile tendency […] to compartmentalize into categories (whereas few human creatures belong entirely to any one’, demonstrating that attempts to stifle queer associations with Lawrence’s text instead proliferated them.

The trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover produced multiple and contradictory legacies. The victory of the Defence suggests the waning power of repressive literary censorship and yet their arguments relied on a sexually conservative interpretation of the novel. While this interpretation was prompted by contemporary anxieties about sexual normativity, it inadvertently produced extended discussion regarding the novel’s depiction of anal sex.

The trial’s relationship to queer history is similarly complex, containing repudiations of ‘deviant’ sexualities but also prompting responses from queer writers. Martin Dines, credits the more explicit discussions of homosexuality in Martyn Goff’s novel The Youngest Director (1961) to the liberating effects of the ‘not guilty’ verdict. Whether disavowed or defended, queer sexualities shaped both the trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and its aftermath. Based on this evidence, it deserves to be considered as a significant moment in British queer history.

Gareth Smith is a postgraduate researcher of English Literature at Cardiff University. His thesis examines representations of class and homosexuality in post-war British culture 1945-67, focusing particularly on class difference, citizenship and cultural studies. He has co-chaired the postgraduate research group Assuming Gender.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com