In 1991, the Progressive Liberal Party government amended the Bahamas’ Sexual Offences Act, decriminalising “buggery” and other same-sex sexual acts in private. Over twenty years later the Bahamas still remains ahead of the majority of its Caribbean neighbours. Male-male sexual activity continues to be illegal in eleven Caribbean nations. Female-female sexual activity is illegal in seven. The Caribbean region also has some of the world’s most severe punitive laws relating to homosexuality. And it is no coincidence that, after sub-Saharan Africa, it has the second highest rate of HIV-prevalence. 32.9% of Jamaican men who have sex with men are HIV positive – the world’s highest prevalence rate among this particularly vulnerable population. Anti-gay laws have institutionalised a toxic homophobic environment that prevents LGBTQ persons from seeking the prevention and care they are entitled to.

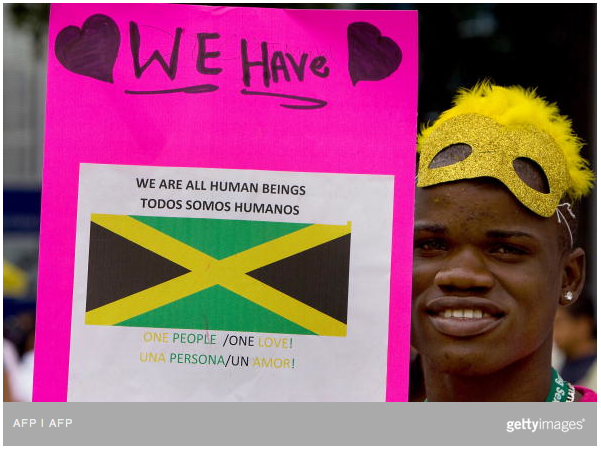

Anti-discrimination movements and efforts to dismantle punitive legislation are gaining a fragile momentum throughout the region, and appeals to history form a substantial part of the rhetoric on both sides of the debate. Both pro- and anti-gay activists draw on a language of colonialism, nationalism and racial tension to articulate viciously conflicting points of view.

The anti-gay legislation in the English-speaking Caribbean is derived from the British 1861 Offences against the Person Act. The Jamaican law, for example, retains a Victorian flavour:

Whosoever shall be convicted of the abominable crime of buggery with mankind or with any animal, shall be liable to be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for a term not exceeding ten years.

One of the more unique legacies of the British Empire is that while only 25% of non-Commonwealth countries criminalise same-sex activity, almost 80% of ex-British colonies maintain anti-buggery and anti-sodomy laws. There was something distinctively pernicious about British colonial rule and its attitudes towards sexuality.

In a 2012 speech Sir Shridath Ramphal, the former Secretary-General of the Commonwealth, insisted that criminal sanctions against homosexual acts are colonial legacies that were never a part of the indigenous cultures on which they were imposed. In reference to postcolonial societies more generally, historians such as Marc Epprecht have argued that colonisation fundamentally altered ways of thinking about sexuality and masculinity. Jamaican Activist, Dadland Maye, said, “The sodomy laws are legislative hate-gifts given to Jamaica by its colonial master, England.” Activists construct mythologised depictions of indigenous cultures that reflect a negation of everything Western rule imposed, including homophobia. Advocates for gay rights have turned the history of colonialism into a usable past and drawn out narratives that support claims of identity and authenticity.

In contrast, many anti-gay activists make use of this same past to argue that homosexuality itself, rather than homophobia, is one of the many products of morally degenerate colonial culture. Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe, champions the purging of homosexuality as necessary to eliminate the last traces of colonial influence. He narrates a history in which the British Empire imposed anti-gay legislation in order to counter an imported decadence that did not exist in uncolonised native cultures.

Similar discourse exists in the Caribbean where pro-gay activities are seen as neo-colonialist projects: covert attempts to impose a Western system of morality on countries no longer under external rule. In 2013 several religious figures in Jamaica led a revival meeting to oppose efforts to overturn the Caribbean country’s anti-sodomy law. Church of Christ pastor Leslie Buckland claimed gay rights activists are trying to “take over the world.” Caribbean conservative groups have thus manipulated the debate over gay rights and punitive legislation into an injunction against perceived neo-colonialism.

Both anti-discrimination and pro-gay activists appeal to features of a pre-colonial past and a supposedly postcolonial present to advocate for change. Operating within the same discursive realm, anti-gay campaigners make recourse to an imagined, insidious legacy in order to defend the status quo. The vestiges and continuities of colonialism and slavery act as central organising forces in the Caribbean – so much so that Caribbean leaders are planning to seek reparations from the former slave-owning states of Europe. If nothing else, this rhetorical dance around gay rights reveals the ways in which the tools of history – a real or imagined past – can be wielded in a highly-contentious present.

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a PhD Candidate at King’s College London, researching the history of breast cancer in nineteenth-century Britain and the US. She is broadly interested in issues of gender, sexuality and race, as well as NHS reform and global health. She works for a small women’s health charity that advocates for sexual & reproductive rights in sub-Saharan Africa. She tweets from @agnesjuliet.

Agnes Arnold-Forster is a PhD Candidate at King’s College London, researching the history of breast cancer in nineteenth-century Britain and the US. She is broadly interested in issues of gender, sexuality and race, as well as NHS reform and global health. She works for a small women’s health charity that advocates for sexual & reproductive rights in sub-Saharan Africa. She tweets from @agnesjuliet.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Reblogged this on Oren Stark.

Reblogged this on Oren Stark.

Pingback: Exploring Queer Caribbean Leaders in Pride – Feminitt Caribbean Blog