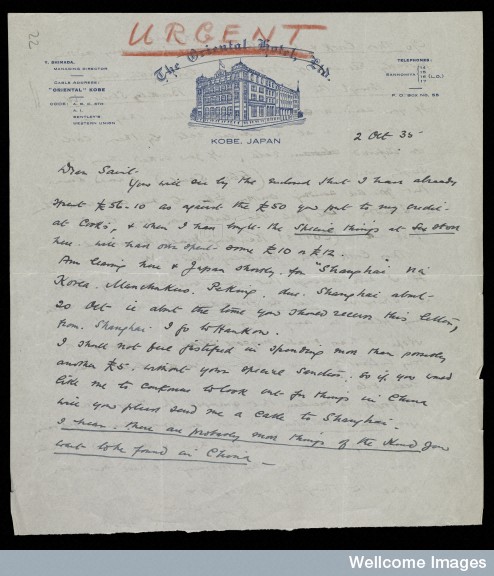

A letter dated 2nd October 1936, headed with the logo of The Oriental Hotel, Kobe, Japan and the large underlined word ‘URGENT’, reads “I have bought the special things at sex store…” [original underlining]. The letter is from Montague Henry Knapp, a retired naval captain and collector, to Peter Johnston-Saint, the conservator of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum. Although the archives at the Wellcome Library, in which the letter is kept, provide a rich source of material for the study of historical attitudes towards sex and the human body, it is little known that the pharmaceutical giant and millionaire, Sir Henry Wellcome, himself had a special interest in this subject.

Intimate Worlds: Exploring Sexuality Through the Wellcome Collection at Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter (5 April-29 June 2014) is the first dedicated display of sexually-related artefacts from across world history which were carefully and deliberately acquired in the early twentieth century as part of Wellcome’s vast and enormously varied medical history collection. Knapp’s letter is displayed alongside other materials from the archives that demonstrate the lengths Wellcome went to acquire objects representing the history of sexuality. The successful results of Captain Knapp’s hunt through the Orient for erotic treasures on Wellcome’s behalf are represented by, for instance, a tiny ivory clam shell made in the nineteenth century, which opens up to reveal a naked Japanese woman enjoying an erotic image.

Also displayed are the conservator Saint’s own reports of collecting sprees around the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Wellcome sent Saint to the famous ‘Gabinetto Segreto’ at the Naples National Archaeological Museum to study the phallic and sexual antiquities from the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. In the exhibition are copies of the best material from this ‘secret’ collection, such as a wind chime shaped as a gladiator who is having to fight his own penis as it has transformed into a panther. The original probably used to protect a home or family business in Pompeii.

Where restricted access collections like that at Naples have encouraged historians to focus on the modern censorship and repression of sexually-themed artefacts, Wellcome’s story shows a deliberate engagement with such ‘troublesome’ objects. For Wellcome, the subject of sex was part of a serious, ‘scientific’ study of human culture and its responses to health and wellbeing. In this he followed contemporary sexologists, with whom he had some limited contact. His fascination with medical responses to sex is represented in the exhibition by an eighteenth-century ivory dildo and an early twentieth-century metal device for the penis to prevent night-time erections.

Wellcome was particularly influenced by the anthropological theory of ‘phallic worship’, which, since the eighteenth century, had seen European gentleman collectors scramble to acquire phallic imagery from as many cultures as possible, in order to prove the universal connection between sex and religion. In the exhibition is a small pamphlet on ‘the collection of information and material among Primitive Peoples’, which Wellcome sent to people travelling in the colonies and new worlds. In this he requests ‘phallic emblems or fetishes, or other objects fashioned in the shape of genital organs’. In addition to phallic deities and votive vulvas, Wellcome’s interest in the sacred and sexual combined is found in the exhibition in ancient Peruvian (Moche, Chimú-Inca) ritual pots depicting fellatio and anal sex (of the sort which later fascinated Alfred Kinsey) and akua’ba (fertility dolls) from contemporary Ghana. Wellcome acquired these together with similarly explicit objects, which he believed were used for supernatural protection, from the supposedly ‘civilised’ cultures of Greece and Rome. The idea of trans-cultural ‘phallic worship’ had long been used in the negotiation of the concepts of the ‘primitive’ and the ‘civilised’, and the role of religion, sexuality and sexual imagery within ‘pagan’ cultures, as an alternate to the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Intimate Worlds deliberately invokes Wellcome’s fascination with the variety and complexities of how sex has been understood across cultures (while acknowledging the limits of his colonial, heteronormative and phallocentric interests – there is a noticeable lack of same-sex sexualities, for example). It has been organised in conjunction with the University of Exeter’s award-winning Sex and History project, which uses objects from the past as a springboard for discussing sex and sexual health. In addition to projects with local schools and groups, a teaching resource pack has been developed with education experts on using objects from the exhibition in Relationships and Sex Education. Striking images from past cultures have been found to be a highly effective way of tackling tricky topics such as pleasure, consent, gender and the role of sexual imagery in forming expectations and attitudes for young people today. As for Wellcome, these objects continue to act as powerful and immediate ways of looking to the past in order to open up discussions about sex and sexuality today.

Intimate Worlds: Exploring Sexuality Through the Wellcome Collection is on until 29th June 2014 at Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter. Sex Saturday, a day of talks, tours and discussion on the history of sexuality is on 7th June.

Jennifer Grove is a researcher at University of Exeter’s Sex and History project and co-curator of Intimate Worlds exhibition. She has recently completed a PhD in Classics and Ancient History at Exeter on the collection and reception of sexually themed antiquities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. She tweets from @jenniferegrove

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com