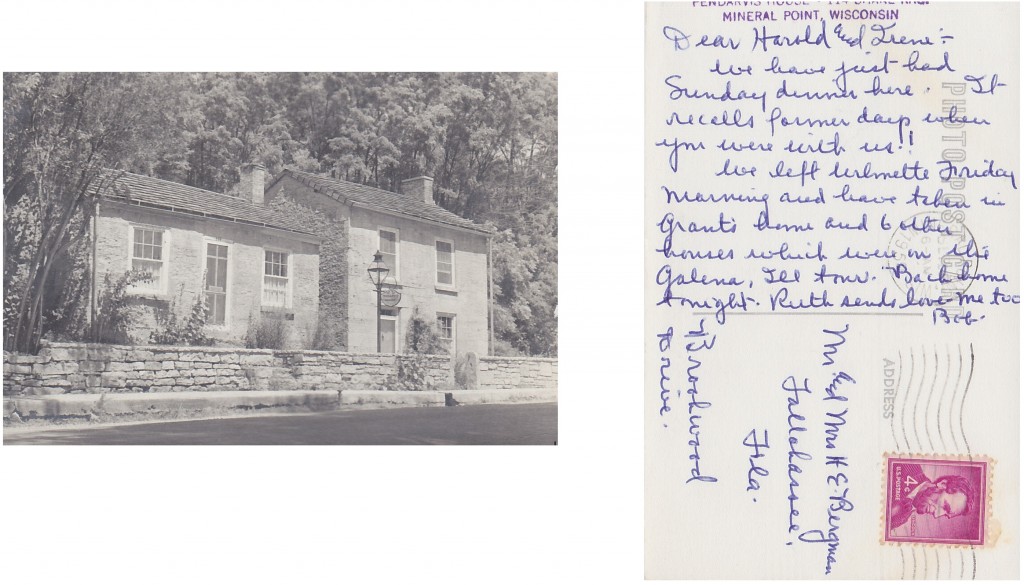

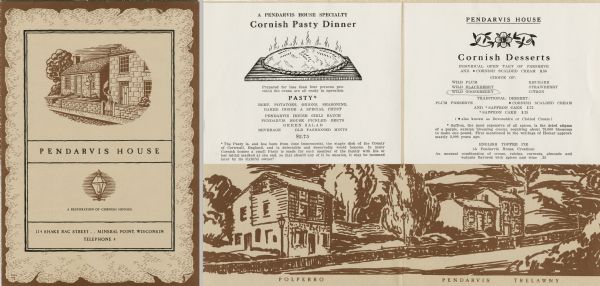

Shoulder steak, onions, potatoes, kidney suet, salt and pepper – this collection of simple ingredients, wrapped in a basic pie crust, composed a dish that during the 1950s and 1960s became the widely renowned Cornish pasty of the Pendarvis House restaurant in Mineral Point, Wisconsin. The Cornish dinners served at the small lead miner’s cottage built in the 1840s garnered rave reviews by well-known American food critics such as Clementine Paddleford and Duncan Hines. The tiny restaurant tucked into the rolling hills of rural southwestern Wisconsin also appeared in the pages of publications like Gourmet magazine and was listed as one of the top seven restaurants in the nation by the Saturday Evening Post. It was also owned and operated by two queer men, Robert Neal and Edgar Hellum.

Despite the restaurant’s out-of-the-way location, the glowing recommendations of Pendarvis House did not go unheeded, as scores of diners flocked from all over Wisconsin and beyond to eat pasty in the one-room cottage and tour the ever-growing complex of historic buildings. But why all of this attention for a meal that was, as the proprietors themselves often admitted, essentially “peasant food”? Much of the answer lies not in the food itself but in the queer men and the queer performance they provided. In their tiny stone cottage, Neal and Hellum leveraged and curated a particular vision of the Cornish history of their small town, resulting in a queer domestic performance that elevated the simple pasty to a luxurious, gourmet meal, enveloping diners in an experience at once historic, exotic, and queer.

In his study of the domestic lives of twentieth-century queer men in London, historian Matt Cook describes domesticity as “that elusive quality that made a ‘house’ a ‘home.’ It suggested clearly defined gender roles, and emotional, relationship and sexual lives enclosed within four walls.” To queer domesticity, then, according to historian Nayan Shah, is to upset “the strict gender roles, the firm divisions between public and private, and the implicit presumptions of self-sufficient economics and intimacy in the respectable domestic household.” Such was the case with Neal and Hellum. Their home, and in many ways their lives, were open to the public. The private space of their home became the public space of a restaurant, and their partnership – both in business and in life – was on display. Moreover, the entire operation was predicated on an inversion of gender roles, an inversion that saw two queer men taking on the role of housewives. This sort of gender inversion had long been understood as a marker of homosexuality and in other contexts drew theatergoers, film audiences, and tourists, who sought thrills outside the sanctioned bounds of normative society. For Pendarvis guests, flaunting convention, if only for the duration of a meal, was as important as a well-made pasty. Indeed, at Pendarvis House, the two went hand in hand.

In their restaurant, Neal and Hellum were not performing the role of just any housewife, but their particular version of the Cornish housewife. In the 1820s, over a century before the restaurant became a tourist attraction, Mineral Point was a predominately male lead-mining outpost. A decade later, the town was a permanent settlement as entire families began moving to the region. This particular migration included a large influx of Cornish immigrants who brought to the area their knowledge of hard-rock mining. While the men brought their mining skills, Cornish women, according to Neal and Hellum’s self-consciously narrated history, brought domestic stability to the region, a stability that included the pasty and the intriguing practice of the shake rag.

Neal and Hellum explained to their guests that when Cornish women had finished preparing the noon-day meal, the housewives would stand outside their cottages and wave handkerchiefs in the air to signal to the men working the mines on the opposite hill that dinner was ready. This strictly gendered domestic practice gave rise to the name Shake Rag, a practice that Neal and Hellum adopted for both their restaurant and their preservation project. They even went so far as to request the city change the name of the street that ran in front of Pendarvis House to Shake Rag Street, a request that was granted in 1949 and followed by a state historical marker two years later.

Neal and Hellum’s story of the Shake Rag, however, was false. But its continued use spotlights how the partners self-consciously crafted and marketed a domestic past that they queerly reenacted for visitors. In 1953, the partners received a letter from the National Trust for Historic Preservation explaining that the name Shake Rag did not reference women shaking rags after their husbands and sons, but was instead “a mocking nickname, implying hunger or beggarliness.” Indeed, “Shake Rag” marked this part of Mineral Point as run-down, shoddy, and impoverished. Such connotations do not sell pasties. In contrast, a portrayal of an idealized domesticity, however queerly rendered, proved profitable. As Hellum put it, dinners at Pendarvis House were a show and the restaurant “like a theater. We set the stage, you see.” Visitors received personal tours of the grounds and buildings stockpiled with luxurious antiques a Cornish family could only have dreamed of. And all were party to a well-rehearsed meal. The star of the show – the pasty – took center stage right at the start (along with relish and pickle trays). At the appointed time, Neal would enter the dining room with the family-sized pasty on a large serving platter. “This is your pasty,” he would say. “It was made especially for your party.” The supporting characters would follow: a second course of salad and crackers and a final dessert course usually featuring Cornish saffron cake, clotted cream, and fruit preserves. But there was not a Cornish housewife in sight.

In the end, it mattered little whether or not the story of Shake Rag was true and it mattered even less that the pasty was nothing more than a basic meat pie. Instead, what ultimately drew many visitors to Pendarvis was the domestic performance of Neal and Hellum. Consciously or not, these two queer men – one a quarter Cornish, the other thoroughly Norwegian – capitalized on people’s fascination with the curated and idealized past the partners reenacted. Here, in a small Wisconsin town, were two men living together, cooking, baking, decorating, serving food, selling antiques and in so doing, magically resuscitating homes doomed to be razed. The queerness of Neal, Hellum, and their business was there for all who chose to see it and all who chose to participate. One such visitor, a Madison newspaper columnist, asked of Neal, “Who are you? The Fairy Prince with the Magic Wand?” To which Neal replied, “No, I’m just Robert Neal of Mineral Point.” As it turns out, he and Hellum were both just regular guys and fairy princes, and their queer performance kept the magic of Pendarvis House alive for nearly forty years.

Christopher Hommerding is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include LGBT and Queer history, with a focus on Midwestern rural and small-town spaces. His dissertation, titled “The ‘Faeries’ of Mineral Point,” explores the lives of two queer men in twentieth-century small-town Wisconsin.

Christopher Hommerding is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include LGBT and Queer history, with a focus on Midwestern rural and small-town spaces. His dissertation, titled “The ‘Faeries’ of Mineral Point,” explores the lives of two queer men in twentieth-century small-town Wisconsin.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

I feel like perhaps you’re overusing the word “queer” in this article. Sometimes relying on a word to describe a situation ends up actually making it harder to understand rather than easier. What do you actually mean by “queerly re-enacting” something. Do you just mean they were re-enacting it AND they were queer men or do you mean that there is something innately queer in the way that they re-enact it. Queer in the space of this short article over 20 times and yet you fail to ever really explain what you mean by that.

What is queer domesticity? Is it just queer men performing housework or is there something about queerness that actually alters the roles they are performing.

Otherwise a very interesting article and insight into an area of history that is often left uncovered.

Hi,

I discovered your blog post because I was searching for an image of the Pendarvis House pasty. I had made a recent visit there and wanted to make one just like it. My question, did you need to pay for the images you posted from the Wisconsin State Historical Society, or was stating their source and serial number all you needed to do? I wrote a blog also on Pendarvis but am working on fleshing it out more. Thanks in response for your reply, have a good day!

Hi Laurie. I’m an editor at NOTCHES. Unfortunately, we no longer have the author’s contact details, and so your message has not been forwarded to him. For questions about reproduction of images, you’ll need to contact the Wisconsin State Historical Society directly.

Thanks!