Moderated by Regina Kunzel

Edited by Devin McGeehan Muchmore

What can histories of sexuality and gender tell us about the carceral state?

The United States’ incarceration rate has quadrupled since the 1970s, giving the U.S. the largest prison population in the world. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics, over 2.2 million people were confined in U.S. jails, prisons, and detention centers at the end of 2014, and an additional 4.7 million were subject to probation or parole. Most are African American and/or Latinx.

As several recent journal issues make clear, U.S. historians have begun the difficult task of unearthing the roots of the mass incarceration crisis. Their work is not confined to the history of prisons but rather analyzes the contours of a broader “carceral state,” the diffuse constellation of correctional facilities, detention centers, law enforcement agencies, policies, non-governmental institutions (both for-profit and non-profit), and ideologies underpinning state investment in policing, confinement, and punishment.

To contribute to this effort, we invited Regina Kunzel to moderate a three-part roundtable on histories of sexuality and the carceral state. In this first post, four innovative historians (Jen Manion, Sarah Haley, Scott De Orio and Elias Vitulli) reflect on the payoffs of bridging these fields, touching on everything from prison sex scandals to the state’s management of gender non-conformity.

Regina Kunzel: First, let me say how excited I am to be in conversation with the four of you about histories of sexuality and the carceral state. I’m interested, first, in your thoughts about a basic question regarding the field. A new history has emerged in the past few years, in conversation with critical prison studies, which tracks the emergence and consequences of an investment in incarceration. What is to be gained by bringing questions of sexuality and gender to that project?

Jen Manion: This is such an important question because gender and sexuality play a crucial role—along with race and class—in shaping the carceral state, and yet have been largely overlooked by generations of historical work on the origins of the penitentiary. The question of prison sex, for example, informed two major “sex panics” that dramatically influenced the penitentiary’s creation and expansion.

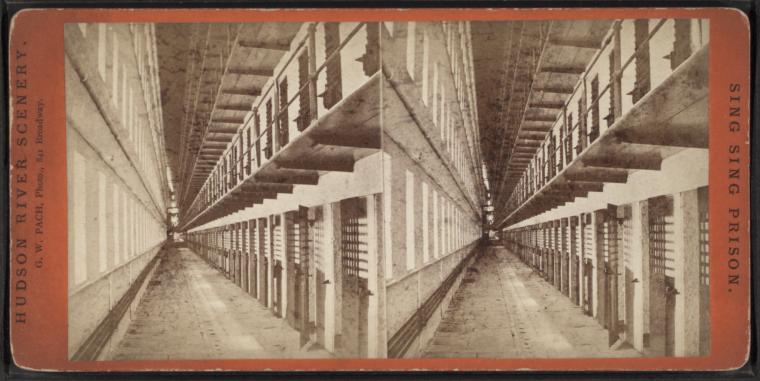

One began in 1785 when a grand jury visited the Philadelphia county jail and noted that men and women were held in large rooms together and were able to have sex with each other. This inspired outrage among white male Protestant reformers and marked the beginning of a movement to segregate and classify prisoners, first by sex and criminal classification and later by race and age. The second occurred in 1826 when reformers learned that numerous men were having sex with each other in prisons throughout the country. This served as justification for the more widespread adoption of solitary confinement, which is still widely used despite substantial evidence that it is a form of torture. So, the carceral state has gone to great lengths to regulate sex!

No matter what arm of the carceral state you look at—from the establishment and enforcement of laws to the organization of prisons, asylums, and almshouses—gender and sexual norms influenced who was targeted and how they were treated. Black women outnumbered white women in the nation’s first penitentiary long before black men came to outnumber white men. Even just asking the question of ‘gender’ reveals some surprising results about the similarities and differences between men and women who were incarcerated. In the earliest decades of the penitentiary in the U.S., the large majority of both women and men imprisoned were convicted of petty larceny. Despite this relative gender balance, women were more likely to be charged as accomplices (storing, possessing, or selling stolen goods) and less likely than men to commit grand larceny.

It is also worth noting that for the early part of U.S history, from the American revolution in 1776 until the Civil War began in 1861, there was little interest in prosecuting men for engaging in sodomy, shutting down brothels, or arresting women for sex work. The significance and apparent threat of cross-dressing only became more pronounced after the mid-nineteenth century. While people were arrested and generally quickly released under general anti-vagrancy laws in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, by the 1850s cities and states across the country began adopting specific anti-cross dressing legislation. By identifying moments when particular restrictions on gendered or sexual behaviors were introduced, historians of sexuality can help us understand what broader social, economic, or political conditions contribute to an expansive penal state.

The association between criminality and queerness is longstanding. Penal systems have played a powerful role in regulating and shaping queer identities and communities. For so much of the past, in so many diverse times and places, laws against sodomy and individual cases have been our primary record of same-sex sexual encounters. Analysis of the regulation of these encounters formed the heart of the field of the history of sexuality in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for decades. And yet we must connect these findings to the growing body of scholarship on carceral histories. So much exciting work remains to be done at the intersection of LGBTQ studies and the carceral state—I look forward to this conversation!

Sarah Haley: I’m really excited to be part of this conversation! Jen Manion put it so well when they said that gender and sexual norms have historically influenced every arm of the carceral state, including who was targeted and how they were treated.

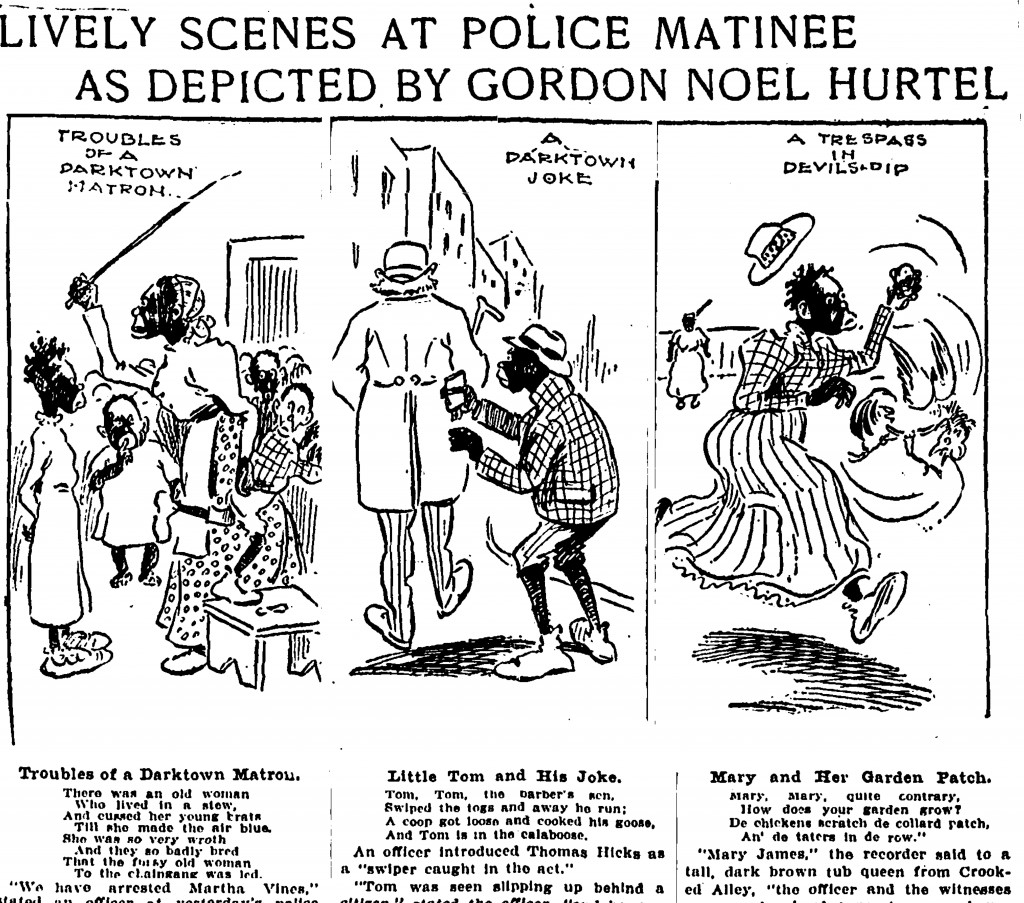

In the field of southern carceral history, which has been one of the richest, most voluminous subfields of American penal history for decades, gender and sexuality have been underexplored. There are important exceptions, including work by Mary Ellen Curtin, Ethan Blue, Talitha Leflouria, but at least one prominent historian of convict leasing stated during a public talk that, in his words, “there were not enough women to matter” to southern punishment history. Since imprisonment is a stark exercise of power and, to quote Joan W. Scott, “gender is a primary way of signifying power,” it is striking that questions of gender are sometimes still reduced to those relating to women and the question of women’s importance is reduced to numerical representation. If numbers of prisoners were the only metric of significance, the history of the emergence of the penitentiary would matter little compared to post-1970s histories of incarceration.

Gender and sexuality are categories of analysis that reshape questions, helping to demonstrate that “mass” is only one important aspect of histories of incarceration and policing. In fact, it is the exclusion of specific categories of people that is sometimes significant. In Georgia between 1906 until at least 1938 white women were the only people almost entirely excluded from chain gangs by both law and custom; imprisonment was an infrastructure that codified womanhood as a racially specific category and white women’s exclusion was a precondition for establishing the chain gang. Understanding the work of imprisonment, its power to shape social and political relations, to build economies, and to impose violence, requires more than the quantification of bodies.

For example, quantification cannot adequately explain the character and significance of carceral sexual violence, which was routinely inflicted upon imprisoned men and women in the South following the Civil War, and which continued into the early-twentieth century. Records from the first decade of the twentieth century reveal that imprisoned men were beaten routinely and unmercifully in the South for sodomy; rape was institutionalized in convict labor camps as guards sexually assaulted black women with impunity, often resulting in pregnancies and childbirths. Carceral sexual violence was not a simple technology of labor management, but rather a more complex mechanism of racial labor control, functioning to signify authority, to humiliate, and to devastate as part of the process of demonstrating white superiority and black servitude. Sexual humiliation was deemed essential for the project of Jim Crow modernity. In southern convict camps public, spectacular, performances of sexualized assault were routine; in addition to the sodomy whippings (which were public), naked imprisoned black women were whipped in sexually suggestive poses for all prisoners and guards to view, signifying gendered racial difference and “the rules of social relationships,” as Scott has put it, in this case the primacy of white political authority. The southern prison camp was, in some ways, a pornographic stage where coerced sexual performances were carceral business practices that contributed to broader structures of gendered racial capitalism.

Historians including Regina Kunzel, Kali Gross, and Cheryl D. Hicks have demonstrated that the nexus of carceral state and sexuality history can generate a reassessment of modern sexual culture, sexual subjectivities, and desire. In the South, imprisoned black women created blues compositions that satirized (rather than demonized) sex work, for example setting the thinly veiled question “anybody here want to buy some cabbage?” to music. Investigating the relationship between sexuality, gender, and carcerality is incredibly generative for interpreting U.S. history: prison archives illuminate hidden dimensions of modern social and cultural life, and centering gender and sexuality expands our understanding of the role of punishment in producing political knowledge and social and economic structures of power.

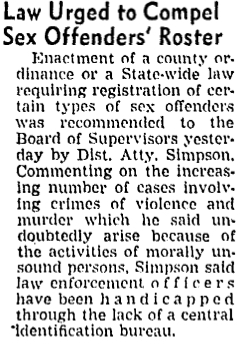

Scott De Orio: I’m delighted to be a part of this conversation! As Jen pointed out, the policing of sexuality played a key role shaping the formation of the modern penitentiary in its early days. Likewise, the criminalization of “sex offenders”—people whom the state stigmatizes as deviant because of their sexual behavior—was crucial to the expansion of the U.S. carceral state in the twentieth century.

Efforts to control deviant sex have been central to the expansion of the U.S. carceral state in ways that historians are only beginning to recognize. In the 1930s, law enforcement and other agencies at every level of government launched what J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, called a “War on the Sex Criminal.” Between 1937 and 1967, 26 states and the District of Columbia passed laws allowing for persons determined to be “sexual psychopaths” to be confined indefinitely in state hospitals. As Estelle Freedman has argued, the sexual psychopath laws reflected a new concern on the part of the state with controlling male sexuality coded as dangerous and uncontrolled. California established the first sex offender registry in the nation in 1947. In the 1950s, crusaders against sex offenders targeted homosexuality in particular. There was a purge of hundreds of employees suspected of being homosexuals from the federal government in 1950, and there were intense police crackdowns on gay men in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1954, and Boise, Idaho, in 1955.

In the 1970s, gay activists challenged the specific criminalization of homosexuality, achieving the reform of sodomy laws in 29 states by 1979. At the same time, though, an unlikely coalition of conservatives, liberals, and feminists launched a new war on sex with new focal points, particularly rape, child sexual abuse, and then HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. This new war on sex transformed sex offenders into an even more central object of state punishment and control. At last count, there were 843,260 people on the sex offender registry in this country. Between 10 and 20 percent of prisoners in state facilities are serving time for a sex offense; in some states, the rate is as high as 30 percent. It is imperative for historians of the carceral state to make sex central to our analysis, because the “long” war on sex offenders constituted a key engine of carceral build-up in the twentieth century.

But there is another problem that is just as disturbing. The rise of sex offender laws since the 1930s has had tragically repressive effects on non-normative sexual behaviors and relationships. At midcentury, sex offender laws punished gay people for a range of consensual behaviors—even sex between consenting adults in private. Although consensual behaviors that take place in private between adults are now legal, many other sexualities remain vulnerable to criminalization. Indeed, the new war on sex has produced a criminal underclass of people, both gay and straight, who have been convicted of consensual but stigmatized sex: sex involving minors, the production or consumption of pornography involving minors, teen sexting, sex involving HIV/AIDS, sex work, public sex, and sex in prison. Underneath their official purpose of protecting people from harm, sex offender laws also inhibit the flourishing of benign sexual variation. In so doing, they keep us from living in a world in which it is possible to practice diverse styles of sex, relationships, and intimacy.

Elias Vitulli: I, too, am thrilled to be part of this conversation. As Jen, Sarah, and Scott have indicated, addressing questions of gender and sexuality leads to a much deeper and more nuanced understanding of every aspect of the U.S. carceral state. Centering questions of sexuality and gender is particularly important when we consider the carceral state’s investment in containing and punishing deviance, a significant theme throughout each prior response. The carceral state has long played a central role in defining gender and sexual deviance and determining its proper treatment. While that treatment has changed over the past two-plus centuries, policing and legal scrutiny and the confinement of people embodying various forms of gender and sexual deviance in jails, prisons, and other carceral institutions has constructed gender and sexual deviance as fundamentally dangerous, outside the normative citizenry, and properly a primary target of the carceral security apparatus both inside and outside penal institutions.

For example, the carceral state has long been deeply invested in normative binary sex, or an understanding of sex as embodied by mutually exclusive categories of “male” and “female” that are tied to a particular body, especially genital, morphology (i.e. male as penis and female person as vagina) and gendered social norms. By the mid-nineteenth century, as Jen mentioned, gender nonconformity in public space became an important target of police. By the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, gender nonconformity became a significant concern for prison and jail administrators, who understood gender nonconformity as a constitutive sign of homosexuality and a primary source of sexual violence and institutional disorder, particularly in men’s institutions. In other words, it became a threat to institutional security and the normative function of jails and prisons. Thus, the management of gender nonconformity was in response to a panic over homosexuality and is interconnected with the sex panics that Jen and Scott mentioned (perhaps we should say that the carceral state has often been in a panic over sex).

Penal institutions also reproduced normative binary sex and racialized it as white through the development of sex segregation—a key aspect of the modernization of penal institutions—and expansion of the penal system to include women’s institutions in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries in the Northeast and Midwest. Sex segregation was not only a response to concerns about deviant heterosexual sex but also the racialized and sexual implications of incarcerating white women. While black women were disproportionately incarcerated throughout most of the U.S. during this time, as both Jen and Sarah explained, efforts to sex-segregate focused on white women, and the first separate women’s institutions were created to respond to the supposed unique needs of white women by rehabilitating them through teaching White domesticity and sexual propriety. Meanwhile, black women often remained in mixed-sex institutions and were required to labor alongside men in the South, as Sarah discussed, exposing them to greater violence in all regions. In other words, the development of sex segregation as a central organizing feature of carceral institutions alongside the construction of gender nonconformity as a security threat reveals the carceral state’s ideological investment in White gender and sexual normativity as constitutive of freedom, rehabilitation, and security. At the same time, gender and sexual nonnormative expressions—particularly when they are embodied by black and brown bodies—are marked as dangerous and proper targets of carceral violence.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of recent scholarship has been its focus on explicating the carceral state as a centrally important site of social formation and control in the U.S. Much of that work, for good reason, has focused on the centrality of anti-blackness and white supremacy as foundational logics that underwrite and are reproduced within the carceral state. Understanding that racialized gender and sexual normativity are central logics of the carceral state is vitally important to furthering our understanding of carceral power, historically and currently.

Regina Kunzel is the Doris Stevens Chair and Professor of History and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Princeton University. Her most recent book is Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality (Chicago, 2008). She is currently working on a book exploring the encounter of sexual- and gender-variant people with psychiatry in the mid-twentieth-century U.S.

Jen Manion is Associate Professor of History and Director of the LGBTQ Resource Center at Connecticut College. Manion is author of Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015) and co-editor of Taking Back the Academy: History of Activism, History as Activism (Routledge, 2004). Jen has also published essays in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Journal of the Early Republic, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, and Radical History Review. Manion was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society in 2012-2013 to research a new project, “Born in the Wrong Time: Transgender Archives & The History of Possibility, 1770-1870.” Manion tweets @activisthistory and posts articles about contemporary mass incarceration at Liberty’s Prisoners on tumblr.

Jen Manion is Associate Professor of History and Director of the LGBTQ Resource Center at Connecticut College. Manion is author of Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015) and co-editor of Taking Back the Academy: History of Activism, History as Activism (Routledge, 2004). Jen has also published essays in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Journal of the Early Republic, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, and Radical History Review. Manion was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society in 2012-2013 to research a new project, “Born in the Wrong Time: Transgender Archives & The History of Possibility, 1770-1870.” Manion tweets @activisthistory and posts articles about contemporary mass incarceration at Liberty’s Prisoners on tumblr.

Sarah Haley is Assistant Professor of Gender Studies and African American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on black feminist analyses of the U.S. carceral state from the late-nineteenth century to the present, black women and labor, and black radical traditions and organizing. She received her PhD in African American Studies and American Studies. Her first book, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity, which examines the lives of imprisoned women in the U.S. South from the 1870s to the 1930s and the role of carcerality in shaping cultural logics of race and gender under Jim Crow, will be published in April 2016. She has also worked as a paralegal for the New York Office of the Federal Public Defender and as a labor organizer with UNITE-HERE. She tweets from @sahaley.

Sarah Haley is Assistant Professor of Gender Studies and African American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on black feminist analyses of the U.S. carceral state from the late-nineteenth century to the present, black women and labor, and black radical traditions and organizing. She received her PhD in African American Studies and American Studies. Her first book, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity, which examines the lives of imprisoned women in the U.S. South from the 1870s to the 1930s and the role of carcerality in shaping cultural logics of race and gender under Jim Crow, will be published in April 2016. She has also worked as a paralegal for the New York Office of the Federal Public Defender and as a labor organizer with UNITE-HERE. She tweets from @sahaley.

Scott De Orio is a doctoral candidate in History and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His research focuses on the history of sexuality in the twentieth-century United States with a particular interest in the law and state power. His dissertation, entitled “The Invention of Bad Gay Sex,” examines how new sex offender laws constructed a criminal underclass of gay people in the late-twentieth-century United States.

Scott De Orio is a doctoral candidate in History and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His research focuses on the history of sexuality in the twentieth-century United States with a particular interest in the law and state power. His dissertation, entitled “The Invention of Bad Gay Sex,” examines how new sex offender laws constructed a criminal underclass of gay people in the late-twentieth-century United States.

Elias Vitulli is a Visiting Lecturer of Gender Studies at Mount Holyoke College. His research explores the connections between queer/transgender studies and critical prison studies. His current project, “Carceral Normativites: Sex, Security, and the Penal Management of Gender Nonconformity,” explores the history of the incarceration of gender nonconforming and transgender people in the US from the early twentieth century to the present, focusing on the evolution and logics of penal policies and practices. He received his Ph.D. in American Studies, with a minor in Feminist and Critical Sexuality Studies, from the University of Minnesota in 2014. His work has appeared in GLQ, Social Justice, and Sexuality Research and Social Policy.

Elias Vitulli is a Visiting Lecturer of Gender Studies at Mount Holyoke College. His research explores the connections between queer/transgender studies and critical prison studies. His current project, “Carceral Normativites: Sex, Security, and the Penal Management of Gender Nonconformity,” explores the history of the incarceration of gender nonconforming and transgender people in the US from the early twentieth century to the present, focusing on the evolution and logics of penal policies and practices. He received his Ph.D. in American Studies, with a minor in Feminist and Critical Sexuality Studies, from the University of Minnesota in 2014. His work has appeared in GLQ, Social Justice, and Sexuality Research and Social Policy.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com