In 1986, a Filipina working as a dancer and hostess in Matsumoto, Japan, learned that she had AIDS. She had undergone an HIV antibody test while still living in the Philippines, where she engaged in sex work. The woman learned that she had tested positive, however, only after moving to Japan—through a television report from Manila. She voluntarily reported to the immigration office in Tokyo and went back to the Philippines. After her return, the news of a “foreign prostitute” with AIDS triggered the so-called “AIDS panic” in Japan. The media revealed the name and identity of the woman and searched for her customers in the club where she used to work. The mysterious foreign disease thought to affect only gay men in the United States had, it seemed, finally reached Japan—through a foreign prostitute.

n.10_1949.9-1024x620.jpg)

Another “panic” erupted a couple of months later in Kobe. The media revealed that a Japanese woman had contracted HIV, allegedly through a Greek man she used to live with. The media falsely reported that she was a prostitute who had sexual relations with more than a hundred men, including foreigners. As such, the media effectively helped to construct and consolidate the image of sexually-promiscuous women—this time a Japanese—bringing a foreign-born disease into Japan.

The following month, a major Japanese newspaper reported on the case of another Japanese woman who tested HIV positive. This time, she was not a “prostitute,” but a pregnant housewife who previously dated a man with hemophilia using a blood product imported from the United States. The Japanese people feared that AIDS was no longer a disease of prostitutes. The deadly disease, it seemed, was now starting to affect the general Japanese population.

All three cases that caused the first “AIDS panic” in Japan treated women as carriers of (foreign-born) sexual diseases and sources of danger to the well-being of (heterosexual) Japanese (men). These women, however, were not the first HIV/AIDS patients in Japan. In 1985, the Japanese Ministry of Health identified a Japanese homosexual man who previously lived in the United States as the “first AIDS patient in Japan.” Homosexuals were so invisible in Japan that such news still did not provoke immediate alarm among the general public. Even before the announcement, there were some known cases of hemophiliac patients who contracted HIV through unheated blood products. In an attempt to cover-up the use of tainted blood products—a scandal that later evolved into a series of high-profile lawsuits—hospitals and government officials avoided public statement on these incidents. Despite these previous cases, it was the news of promiscuous women influenced by a Western sexual lifestyle that provoked fear and panic among the Japanese.

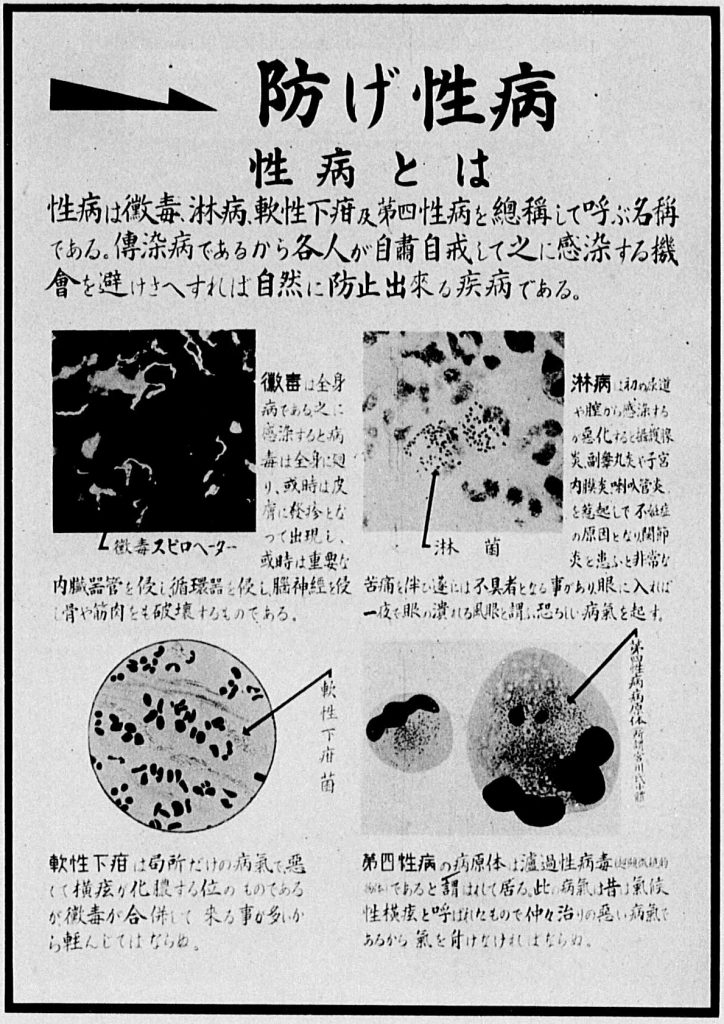

Throughout Japanese history, women had frequently been blamed for infecting heterosexual Japanese men with sexual diseases from abroad. After the country ended its isolationist policy and opened itself to foreign trade in the mid-nineteenth century, the government found the need to regulate Japanese prostitutes catering to Westerners living in Japan. State bureaucrats thus devised a modern system of licensed prostitution based on the model of Western countries, which subjected prostitutes to mandatory medical examinations for venereal disease and criminalized unlicensed prostitutes. A series of laws in the early twentieth century called for frequent health examinations for registered prostitutes and the hospitalization of those affected with VD. The prostitutes themselves paid the fees.

By the 1920s and 1930s, Japanese officials realized that they could no longer contain VD among Japanese prostitutes as it started to spread more widely among Japanese men. Alarmists considered the influx of Western sexual lifestyles as partly responsible for the spread. Unlike the sex work in licensed quarters, the sexuality of waitresses in Western-style cafés and dance halls could not be easily managed. Anti-VD legislations thus shifted the focus away from prostitutes, toward the coverage of the entire population. In 1920, a Japanese feminist group initiated a campaign to mandate VD examinations for all men before marriage. The petition did not pass, however, because it only targeted men as disease carriers. In 1938, a patriotic women’s organization took on the anti-VD marriage prohibition campaign. The new proposal no longer singled out men as carriers of diseases, but asked for strict medical examinations for infected pregnant women and prostitutes.

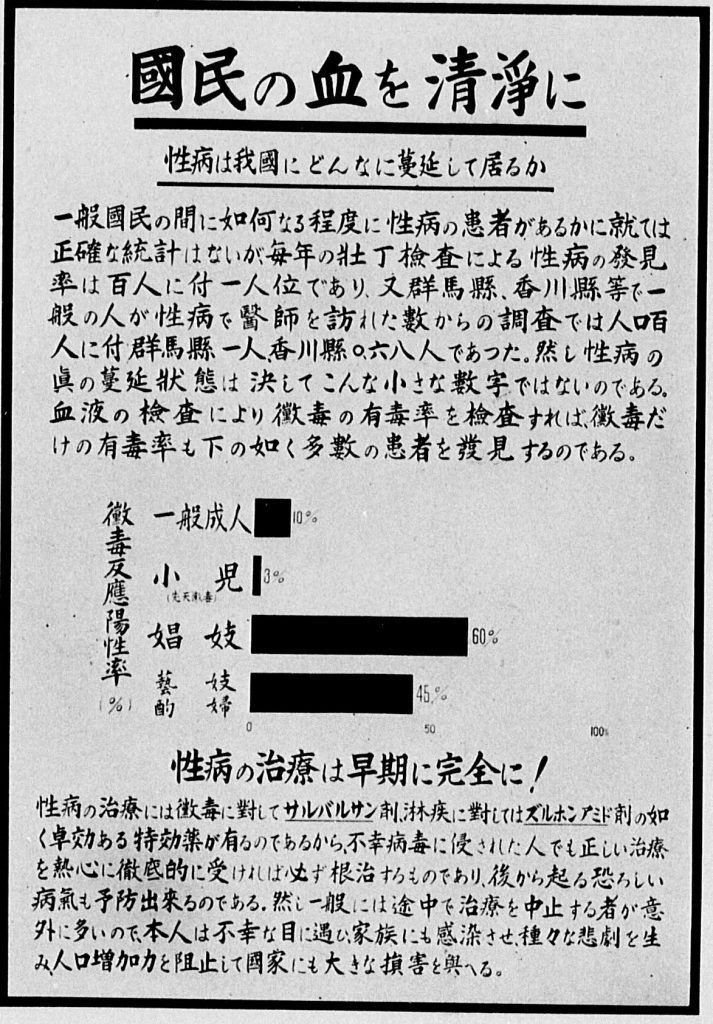

These anti-VD initiatives were eventually incorporated into national eugenic policies to support the war effort. The wellness of the national body—especially soldiers—became especially critical as Japan’s war with China and Western imperial nations intensified in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The Ministry of Health and Welfare established the Eugenics Department, whose main task was to prevent the spread of VD, mental illness, alcoholism, tuberculosis, and leprosy. The Ministry named VD a “poison to the race” (minzokudoku)—along with alcoholism and drug abuse—which could harm the future prosperity of the race. The government thus called for the “purity of the Japanese blood,” while blaming prostitutes and other female “entertainers” as the source of the “poison.”

In the eyes of Japanese bureaucrats and eugenicists, the problem seemed to worsen after Japan’s defeat in World War II. The U.S. Occupation of Japan accelerated the flood of Western culture and lifestyles. Moral conservatives worried about the corruption of sexual morals among the youth. Marriage after courtship (renai kekkon) was starting to replace traditional arranged marriages. Many Japanese feared that young men and women, influenced by romantic relationships depicted in Hollywood films, would blindly marry without looking into the necessary information typically covered in arranged marriages, especially the health history of the couple and their families. Public health offices therefore called for Japanese citizens to exchange health certificates before marriage. In particular, they urged men to get tested for VD and, if infected, to go to the hospital for treatment. Even decent-looking young women, they warned, could have a “filthy” night job.

Local health offices launched a “VD prevention week” in 1949 to raise awareness of the prevalence of sexual diseases, which, they feared, could lead to the extinction of the race. Health officials worried that VD tended to suppress the fertility of those infected. From a eugenic standpoint, they claimed, the lower fertility among “female workers, dancers, actresses, and waitresses” was less of a problem. Such consequences posed a threat to the future survival of the race only when the disease started to spread among the intellectuals and “well-born” families. Officials believed that the gradual removal of “superior genes” through VD could further weaken the defeated race suffering from economic and social hardships.

4報8.10-958x1024.jpg)

By labeling women as the primary source of infection, the government, health workers, scientists, and the media spread negative stereotypes regarding women, foreigners, and their sexualities while neglecting to implement necessary measures to prevent the spread of STDs among and beyond these groups. Female sex workers and foreigners often faced discrimination, such as being denied entry into shops, restaurants, and hotels. Some were even denied treatment in hospitals. Despite the spotlight on female sex workers, there continues to be a general lack of prevention programs and support for this population, especially foreign sex workers. The focus on the supposed danger of sexual contacts with female entertainment workers, moreover, allowed officials and hospitals to overlook larger issues—in the case of early AIDS incidents in Japan, the use of tainted, unheated blood products. The visibility of heterosexual sex with female sex workers on the one hand, and the invisibility of homosexual sex on the other, have also hindered awareness and education of safe and clean sex among the general population, especially youth. Japan is one of the few industrialized nations where the rates of STDs, especially those of HIV/AIDS, are, while generally low, still increasing. Misogyny, xenophobia, and homophobia have proven to be most deadly to the sexual well-being of the Japanese people.

Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci (American Studies, Brown University, Ph.D.) is a historian of reproductive politics, eugenics, and U.S.-Japan relations. She teaches reproductive issues from an international/transnational perspective at Stanford University. Her research has appeared in publications such as Science, Public Health and the State in Modern Asia, Southern Spaces, and the Journal of American-East Asian Relations (a winning essay of the Frank Gibney Award). She is currently completing her book, Conceiving National Bodies: The Trans-Pacific Politics of Birth Control in the United States and Japan, 1920-1960 (under contract with Stanford University Press).

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com