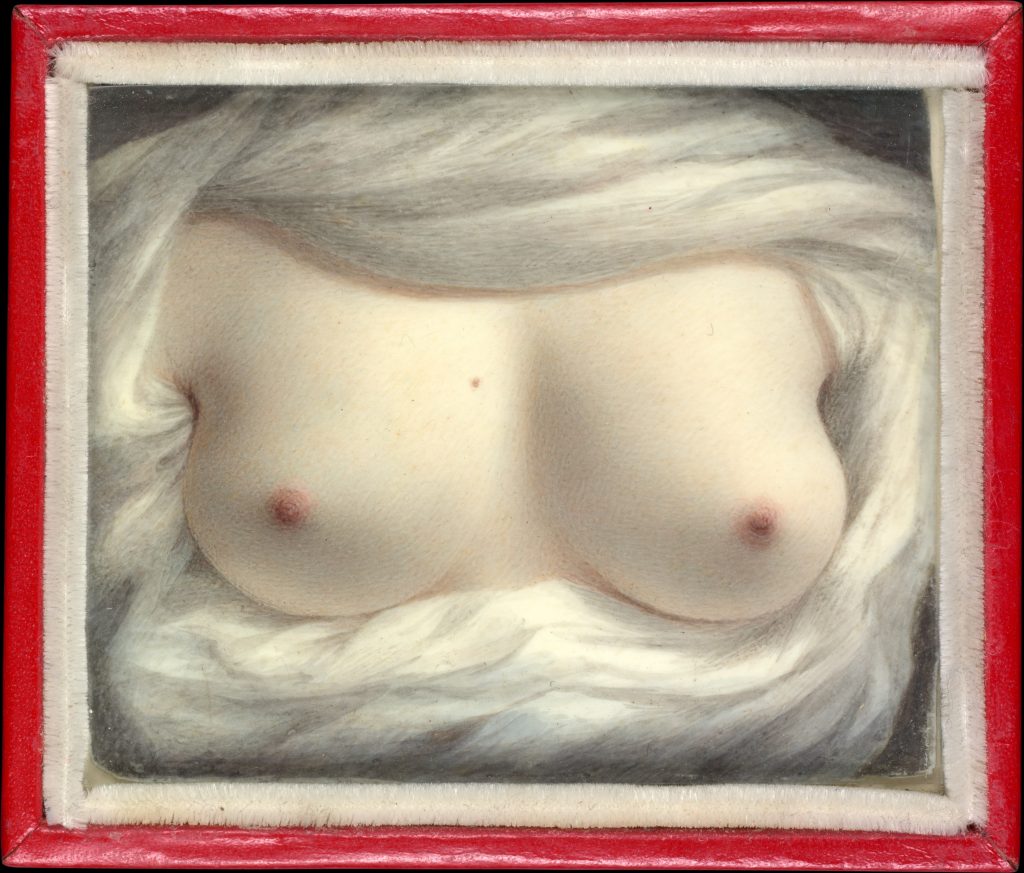

Sometimes objects can illuminate what the written record cannot. Sarah Goodridge’s “Beauty Revealed” is only a 2 5/8 x 3 1/8 inch rectangle of ivory, but it speaks volumes. With vivid realism, it depicts a pair of breasts surrounded by white gauze. That alone would be unusual at the time it was painted in 1828. It is the recipient of this miniature that is most revealing: the famous senator and statesman Daniel Webster. The miniature is the only surviving evidence of an erotic relationship with its artist, Sarah Goodridge (or Goodrich). While the correspondence between this pair is brief and ordinary in an era when plenty of elite men and women were friends, the miniature both opens up and complicates the story of Webster and Goodridge.

Sarah Goodridge was a prominent Boston miniature painter in the antebellum era who had known Daniel Webster since 1819. Goodridge, born in 1788 in Templeton, Massachusetts to a large and poor family, moved to Boston at the age of seventeen to live with her sister and brother-in-law and further her artistic career. She later trained with the famous portrait artist Gilbert Stuart. Goodridge painted many members of the Webster family, and Daniel Webster sat for her twelve times. There is an intimacy that builds up between artist and sitter, particularly a painter of miniatures who must render a face in exact and minute detail, and Webster’s repeated sittings with Goodridge surely strengthened their relationship.

Friendships between elite men and women were in fact quite common in the early nineteenth century, and particularly among intellectual and artistic circles in antebellum Boston. Other artists and sitters formed friendships, notably Goodridge’s famous teacher Gilbert Stuart and several of his female patrons. Intimacy between men and women was not necessarily sexual; there could be emotional closeness, strong affection, and mutual respect. Such relationships could have had physical elements, and surely some did, but this was not the most important or dominant aspect of the relationship. It is also possible, given the risk of the interception of letters and later destruction of letters in order to protect reputation, that some friendships were more physically intimate than the written record suggests. Goodridge and Webster’s relationship is a rare instance in which an object survives that unlocks a new level of understanding.

When Goodridge met Webster, she was a single woman in her early thirties and he was a rising political star six years her senior who had been married for a decade. Throughout the 1820s, both of their careers took off, and Goodridge earned enough to support her extended family (and to stay unmarried). Older, unmarried women with financial stability enjoyed more freedom in their relationships with men than other women, forming ties without having to gain a husband’s approval and being beyond the age when those around them worried she would be seduced. Men often helped such female friends with business matters, and Webster found Goodridge a studio and rooms. Their friendly business relationship continued over three decades, with Goodridge becoming so successful as to lend Webster thousands of dollars.

The only surviving letters between the pair are just over forty short notes written from Webster to Goodridge between 1827 and 1851, primarily discussing financial matters or visits (no letters from Goodridge to Webster survive). The earliest letter includes thanks to Goodridge for her “kind wishes” for Mrs. Webster’s health. Opposite-sex friends often referenced spouses in their correspondence to bring them into the relationship and signal propriety, and in many cases the spouse was a real part of the friendship. Beyond this, the content of the letters tells us little about Webster and Goodridge’s relationship, and they certainly have no suggestions of eroticism or sexual intimacy. Looking carefully at the salutations can reveal more, however. Letter-writing guides and social conventions proscribed particular greetings for people of varying levels of intimacy; friends of the opposite sex generally began with “Dear Sir” or “Dear Madam,” with only lovers or family using first names. The openings of Webster’s letters show the increasing closeness of Webster and Goodridge’s relationship over the years, evolving from “Madam” to “Dear Madam” to “Dear Miss G.” and finally “My dear, good friend.”

Interestingly, the gift of “Beauty Revealed” came fairly early in this evolution. Miniatures of any sort were generally only given to lovers or close family; even a miniature of a face required an intimate interaction that society deemed inappropriate for friends of the opposite sex. The recipient of a miniature would have to hold it close to the face to examine it in detail, and miniatures were often worn at the breast, both of which signaled closeness of bodies. Thus for Goodridge to give Webster a miniature at all was suggestive of romantic ties.

Goodridge traveled to Washington in 1828 to give Webster the unusual image soon after Webster’s wife died. It is possible that with Webster now single, Goodridge felt more comfortable acknowledging an existing or budding sexual attraction. Goodridge could have easily painted a conventional self-portrait miniature to give to Webster on that 1828 visit, knowing that even such a gift would signify to him (and anybody who became aware of the gift) a romantic relationship. But the work she created and named “Beauty Revealed” was groundbreaking both in terms of art and social norms. This miniature, too, could be held close, but it was openly sexual. It clearly attested to an erotic and possibly sexual relationship between Webster and Goodridge.

A miniature focused on breasts was a new innovation; the only other miniatures zeroing in on one body part depicted an eye, and these were done only in Europe in this period. Nude art of any kind was rare in America in this era, and the only nude painting that had been shown publicly in the country was John Vanderlyn’s Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos. This painting drew large crowds when it was displayed at the Boston Athenaeum in 1826. Goodridge had surely seen this painting and it appears to have influenced her work. The shape, size, and coloration of the breasts in Vanderlyn’s image, as well as the surrounding of white gauzy cloth, are quite similar to those in “Beauty Revealed.” Despite the photographic realism of the miniature, these breasts were not purely a replica of Goodridge’s own. However, these are not an artistic ideal or copy, either: Goodridge indicates these were a specific woman’s breasts (i.e. hers) with a small mark on the upper right breast. Webster may or may not have caught the allusion to Vanderlyn, but he surely understood the intimacy of the gift.

We can only speculate about what this image meant to Goodridge and Webster. The gift of only a part of her body, one that is both sexual and maternal, might have gestured to Goodridge’s continuing command over her own body. As a friend or even lover, Webster did not have the unfettered access to her body that a husband would. Goodridge could choose what to reveal to him, and how much to give. But for all the sexual intimacy of this image, it still appears that the pair’s relationship was primarily one of friendship. It seems unlikely that the pair considered marrying. Goodridge would have had to give up her artistic career, independence, and home in Boston. Less than two years after his wife’s death, Webster married a woman fifteen years his junior, but his friendship with Goodridge continued another two decades. They were rarely in the same place, so much of their relationship would have been conducted through letters and was thus by necessity not at most times a physical one. The miniature’s revelation is thus all the more surprising.

Webster clearly valued “Beauty Revealed,” keeping it and another more conventional self-portrait of Goodridge (given years later) until his death. It was not until 1981, when Webster’s descendants put the miniature up for auction, that its existence came to light—and with it, his relationship with Goodridge. These descendants described Goodridge as Webster’s fiancée, suggesting their discomfort with their ancestor’s extramarital sexuality and attempting to reframe possession of the body within the confines of marriage. It was just these sorts of anxieties that challenged men and women of the nineteenth century to be so discrete as to leave only eight square inches of evidence of their sexual attraction.

Cassandra Good is the author of Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Men and Women in the Early American Republic (Oxford, 2015), which received the Mary Jurich Nickliss Prize from the Organization of American Historians. She serves as the Associate Editor of the Papers of James Monroe at the University of Mary Washington and her writing has appeared on Slate, Smithsonian.com, and Mental Floss. Follow her on twitter @CassAGood.

is the author of Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Men and Women in the Early American Republic (Oxford, 2015), which received the Mary Jurich Nickliss Prize from the Organization of American Historians. She serves as the Associate Editor of the Papers of James Monroe at the University of Mary Washington and her writing has appeared on Slate, Smithsonian.com, and Mental Floss. Follow her on twitter @CassAGood.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com