Rachel Barton

Since its founding in 2015, the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project—a community-based organization dedicated to bringing to light the struggles and activist efforts of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community in Southwest Virginia—has worked to preserve and illuminate Roanoke’s queer legacy. One of our major initiatives is the Downtown Roanoke LGBTQ Walking Tour, a community engagement project that seeks to highlight the hidden queer history behind Roanoke’s economic revival.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, Roanoke struggled to address the challenges posed by the steady shrinkage of its previously booming railroad industry. Economic decline transformed its downtown into a center of urban “vice” and economic privation. As in larger cities, such as New York and San Francisco, centers of vice also became centers of LGBTQ+ culture, hosting a number of gay meeting places and activists groups. However, over the past 40 years, successive urban renewal initiatives and gentrification have transformed Roanoke into a city on the make.

As gentrification reshapes Roanoke, evidence of its queer history is disappearing from the landscape. Nearly all of Roanoke’s historical gay bars have been shut down, and the various activist groups that operate in the city are largely overlooked by modern residents. On the tour, we invite participants to reflect upon the relationship between gentrification and the erasure of queer history while engaging in site-specific discussions of displacement, discrimination, anti-gay violence, and LGBTQ empowerment and liberation. What follows is an annotated version of the tour. The themes and topics it explores, reflect a connection between the expansion of gentrification initiatives and queer erasure in “The Magic City.”

The Tour:

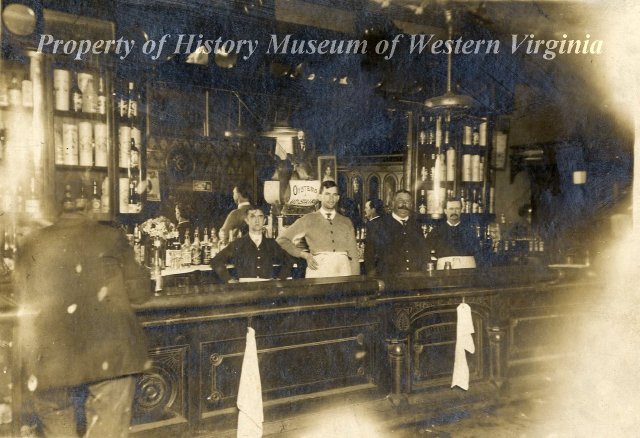

Roanoke’s Saloon District

The tour begins in the nineteenth century on the site of a former saloon district, dubbed “Railroad Avenue” for its location by the train tracks. In the 1890s, Roanoke was home to some 56 distinct saloons, all of which entertained the young, single men who worked on the railroad. Railroad Avenue was also the heart of the city’s prostitution economy. As the city’s bachelor population continued to grow into the early twentieth century, prostitution became an increasingly vexing problem for local government. Even after the railroad’s decline, sex workers remained in demand and politicians worried about the deleterious impacts of prostitution on the city’s downtown. By the turn of the twentieth century, they had pushed this and other “vice” out of the white side of town and into Roanoke’s historically black district, Gainsboro.

Gainsboro and Downtown

Gainsboro’s black residents bore the brunt of the city government’s evolving campaigns to eradicate “vice” and improve the city’s economic fortunes in the second half of the twentieth-century. During the 1950s and 1960s, thousands of black homes and businesses in the neighborhood (seen by the city as dilapidated, burdensome slums) were demolished. Meanwhile, sex workers, including many trans* sex workers, continued to do business downtown. These workers would be targets of Roanoke’s 1970s and 1980s urban regeneration efforts in the city square, which city officials hoped would open up for licit commerce as trans* sex workers disappeared. The city largely succeeded in displacing and erasing the presence of sex workers in the city square. But they could not root out sex work completely. Trans* sex workers moved to other parts of the city, dodging police harassment as they went.

The Last Straw

Themes of displacement, erasure, and persecution are further explored as the tour continues on to the sites of several former gay bars. First, the group stops at The Last Straw (1973-1993), one of the longest running gay bars in Southwest Virginia. Oral histories conducted by the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project describe The Last Straw as a “cruise bar…sterile, in a sense.” It was small, clean, efficient, and populated primarily by gay men. Now, the building is a Christian outreach center. A look inside reveals that the original wooden bar is still intact, the sterility that perhaps once seemed uncanny to cruisers now blends in seamlessly. For tour participants, this gay bar-turned-gospel center exemplifies the discrepancies between present and past, modern appearance, and latent history.

Nite & Day

On Kirk Avenue—presently a downtown Roanoke hotspot for trendy eateries and premium loft apartments—the group visits the site of Nite & Day, a gay bar that opened in 1977 and stayed in business for two years. The Virginia Gayzette, a gay activist publication that circulated in Roanoke intermittently in the 1970s, describes Nite & Day as a small, quiet bar that aimed to be taken seriously and generally supported local gay activist efforts. There was no disco music and no dancing, making it covert enough to attract questioning straight boys interested in cruising. Now, the building hosts an upscale artisan cocktail bar and restaurant called Lucky. A peek through its front windows reveals finely polished tables crowded with sharply dressed young professionals. To modern patrons, the space’s short stint as a gay bar is completely invisible, obscured by an influx of upscale business ventures.

Murphy’s Super Disco

Up the street, the group visits another former gay bar: Murphy’s Super Disco. Open for just over one year (1978-1979), Murphy’s straight owners marketed it as a gay bar to cash in on the pink dollar. According to an oral history interview, the owners “were not ready” to host gay patrons, and put restrictions on the kind of contact customers could have with each other. They were “completely plucked at the sight of two men dancing,” and had a sign advertising anti-gay Alcoholic Beverage Control laws on the front door. Murphy’s Super Disco is now a bar and restaurant that regularly hosts live music shows. Last April, the History Project visited the bar on a queer history bar crawl and several members were warned by a bouncer to “keep it family friendly.” To Project members, this suggested that the establishment was still “plucked” by displays of queer sexuality.

The Metropolitan Community Church

The tour’s next stop—an office building that hosted Roanoke’s Metropolitan Community Church in the late 90s—has served Roanoke’s LGBTQ community as both a sanctuary and as a place of persecution. The MCC was originally founded in 1968 by Troy Perry, a gay man living in L.A. These churches are, at their core, built by and for the LGBTQ community; a place for queer folks to come together and explore their spirituality in a safe environment. But Downtown Roanoke was not always the accepting place congregants hoped it would be. In 2001, a pastor and two congregants were attacked outside the church. According to community members, the police were not helpful in tracking down the suspects. In 2003, the MCC congregation moved to a former Methodist church in Southeast Roanoke, where it remains to this day. Its former site on Kirk Avenue is now the office of Democratic Virginia Senator and former Virginia Governor Mark Warner, who, in 2001, voiced support for extending hate crime protections to include sexual orientation. In 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act finally extended this protection. However, for community members who have faced anti-gay violence, there is still anxiety about how much protection the law can offer.

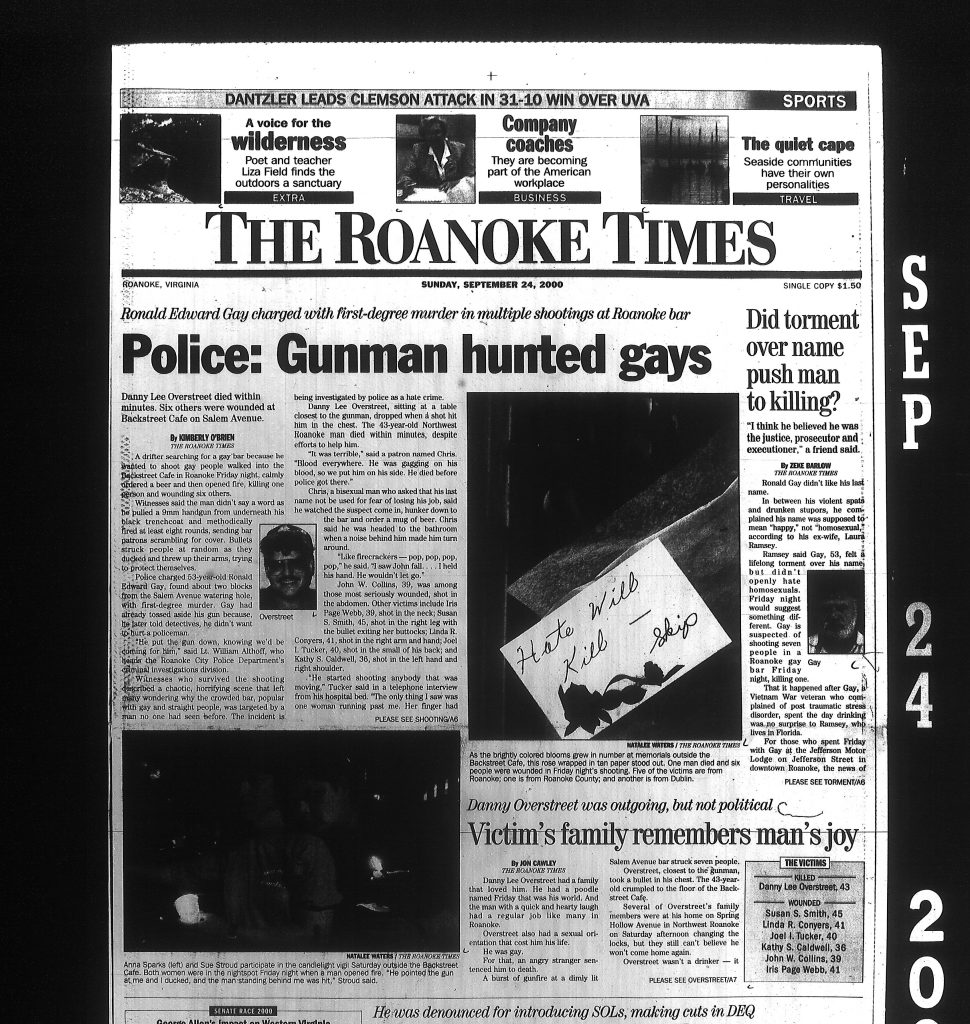

Backstreet

In Roanoke, as in other cities, the realities of anti-gay violence are unknown to many outside of the community, but one highly publicized Roanoke hate crime put anti-gay violence in the national spotlight. On the northern fringes of town, the tour group visits the former site of The Backstreet Cafe, where, in September 2000, a Floridian named Ronald Gay opened fire on a crowd of patrons inside of the bar, killing one man and wounding several others. Afterwards, hundreds of people from inside and outside of the community gathered downtown for a candlelight vigil. National media covered the story, spurring conversations about homophobia and violence. In 2017, Backstreet closed; it is now a sports bar and music venue called The Front Row. From the outside, the building looks dilapidated and nondescript. Many on the tour express not knowing of its existence or being unaware of the shooting. The tour group is generally on the younger side, and several participants are new to the Roanoke area. For them, laminations of old Roanoke Times articles describing the shooting bring up thoughts of the 2016 Pulse Nightclub attack. In the aftermath of the Pulse shooting, online journals like Slate mentioned the Backstreet shooting as an historic example of anti-gay violence in gay bars across America.

Old Southwest

Towards the end of the tour, the group winds around to Roanoke’s Historic Old Southwest district. Once home to wealthy railroad families living in Victorian mansions, Old Southwest was hit hard by Roanoke’s economic recession. From the 1930s onward, house prices plummeted and rent was cheap, attracting a diverse group of residents, including young queer people. Old Southwest became known as Roanoke’s “gay ghetto” and was a center for LGBTQ activist efforts. In 1971, The Gay Alliance of Roanoke Valley (GARV) was founded on Albermarle Avenue. In the late 1970s, the Free Alliance for Individual Rights (FAIR) met in apartments along Mountain Avenue. Now, Old Southwest is a transitional neighborhood; housing restoration projects have brought middle class families back to the area, increasing the standard of living. Though still considered a “gayborhood” by some, even as rent continues to rise and demographics shift, it is unclear whether or not Old Southwest will retain this reputation or if queer folks—particularly working class queer folks—will be displaced to other parts of the city.

The Trade Winds

Roanoke’s “gay ghetto” is also home to the site of Southwest Virginia’s oldest gay bar, The Trade Winds. The Trade Winds might have been a gay bar as early the beginning of the 1960s, and it was the only gay bar in town until The Last Straw opened in 1973. As such, for over a decade The Trade Winds was a center of gay life and activism in Southwest Virginia. After a patron was beaten up outside the bar in 1971, activist group GARV staged a protest on The Trade Winds, encouraging community members to abstain from going to the bar until management properly dealt with the assault. The protest was unsuccessful, but the bar continued as a queer meeting space until it closed in 1983. According to community members, The Trade Winds held Southwest Virginia’s first drag shows, and the Miss Gay Roanoke contest began here in 1974. Now, the building that once hosted The Trade Winds has been demolished. The tour group stands in front of an empty, grass-covered lot; a blurry aerial photograph is all that’s left of what used to be the only space Roanoke’s LGBTQ community had.

Elmwood Park

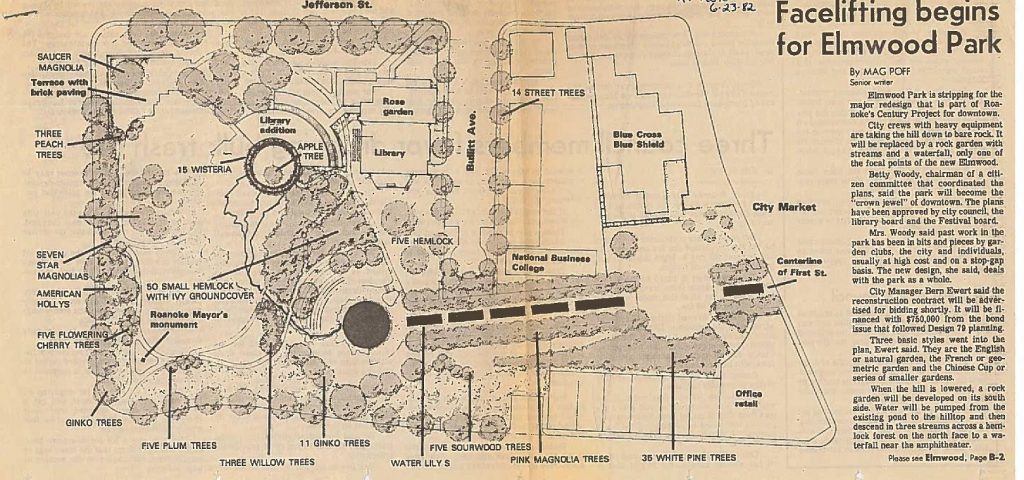

The final stop on the tour takes the group back downtown to the entrance to another notable gay cruising spot, Elmwood Park—now a popular venue for festivals and concerts. Elmwood Park was remodeled during Roanoke’s “Design ‘79” initiative. The park was extended towards the Market Building, and Bullitt Ave, which runs adjacent to the park, was cut off to vehicular traffic. This change effectively ended cruisers’ access to the park and opened it up for other business ventures. Since 2004, Elmwood Park has hosted Roanoke’s Pride in the Park celebration. However, the park’s history as a gay cruising hub is left out of the festivities, replaced, perhaps, by more palatable examples of queer life.

Conclusion

After the tour, participants can’t help but note how much of Roanoke’s queer history is now undermined by new developments. Buildings that once hosted gay bars have now been wiped clean of their queer connotations. Streets frequented by queer sex workers have now been “cleaned up”. These changes have paved the way for innovative new businesses and opportunities, but they have also erased the presence of queer lives: where queers worked, loved, resisted violence, and strove for liberation. As Roanoke moves forward, this tour and other LGBTQ community initiatives will hopefully serve to keep its queer past grounded, lest these people and the legacies they built will be erased from Roanoke’s historical landscape completely.

Rachel Barton is a writer, activist, and amateur queer historian living and working in Roanoke, Virginia. She graduated from Roanoke College with a BA in literature in 2016. Since then, she’s been writing poetry, working as a project member for the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project, engaging in local activism, and preparing for graduate school.

Rachel Barton is a writer, activist, and amateur queer historian living and working in Roanoke, Virginia. She graduated from Roanoke College with a BA in literature in 2016. Since then, she’s been writing poetry, working as a project member for the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project, engaging in local activism, and preparing for graduate school.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com