In this special guest post, Jeffrey Weeks reflects on his 1988 interview with Marc Stein, which appeared in its entirety for the first time on NOTCHES as “Sexual Politics in the Era of Reagan and Thatcher.” Framing this 1988 interview were two important political contexts: Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government had passed Section 28 and Ronald Reagan’s Republican administration was willfully turning a blind eye to the ravages of AIDS. Today, 27 years later, Jeffrey Weeks considers this interview and offers further thoughts on sexual politics and sexual history.

This interview was conducted at a critical moment in the evolution of what was not then called the LGBT world. The period was dominated by the still seemingly out of control HIV/AIDS epidemic, which was devastating the gay male communities of North America in particular, but also a wider circle of equally marginalized groups such as African Americans. (I was actually in Boston, where this interview took place, to give a lecture on the historical and cultural contexts of the epidemic). It really seemed to many embattled LGBT people that we were facing a fundamental existential threat – to our identities and to our lives.

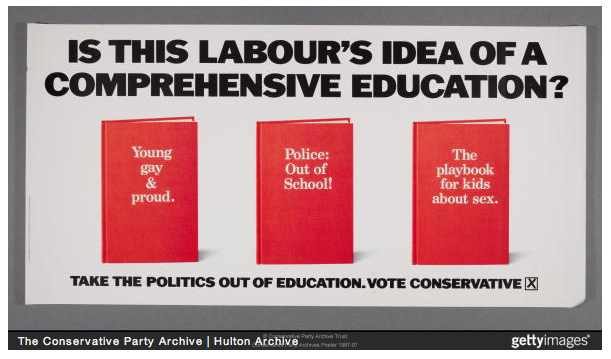

In Britain this acute sense of crisis was compounded by the Thatcher government’s pushing through in late 1987 and early 1988 of Section 28 of the Local Government Act, which outlawed the promotion of homosexuality as a ‘pretended family relationship’. This was more than an abstract threat. I had been at a conference in Amsterdam, entitled ‘Homosexuality, Which Homosexuality?’ at the height of the parliamentary battles over Section 28, in December 1987, and had been a bit startled to hear that I had been denounced by name in the House of Lords by a crusty Tory peer, and quoted on BBC Radio 4, for promoting homosexuality on public funds. My trip had been financed by the British Council. The paper I delivered at the conference was called ‘Against Nature’, a title I also used for a subsequent book, which was intended as an ironic play on ideas of both the naturalness and unnaturalness of homosexuality. In the climate generated by the interlocking impact of AIDS and Section 28 it seemed to be the leitmotif of a harsh political and cultural assault on LGBT people.

Less than thirty years later, we live in a quite different world, at least if we happen to be citizens of the more privileged parts of the globe. The numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS, and the number of deaths from the it, are hugely greater, on a global scale, than they were in 1988, but in the affluent countries especially, thanks to new drug combinations, AIDS has become a chronic but manageable disease rather than an acute epidemic. Section 28, along with other anti-homosexual restrictions, has long disappeared from the statute book in Britain, and though it was not quite the ‘dead letter from the start’ that I described in the interview, and had a chilling inhibiting effect on the open discussion of homosexuality in schools and local authorities, no-one was prosecuted through it. And as for ‘pretended family relationships’: civil partnerships, same-sex marriage, a lesbigay baby boom, equal adoption, access to surrogacy rights, gender recognition changes, and a more open, and digitalised, cultural climate have transformed the meanings of family and the possibilities of intimate life for LGBT people, in Britain and other parts of the world.

This is not to discount the continuation of homophobia, biphobia, transphobia or racism even in the ostensibly liberalized countries of the Global North, let alone the fundamentalist and ultra-nationalist backlash against same-sex and gender diversity elsewhere. As ever in the history of sexuality, change is complex, contested, partial, uneven, and contradictory in its impact. There is no divine or secular motor of change, no pre-ordained direction, no unproblematic or unchallenged goal. And yet fundamental changes have occurred, positive and negative, that require analysis and understanding, and an acute sense of the politics of sexuality – tasks that provide the continuing raison d’etre of sexual history even as it has increasingly become mainstreamed and depoliticized (where it hasn’t been queered to abstraction).

When Marc Stein contacted me to say he had come across this 1988 interview I must confess that though I could remember the interview I had no memory at all of what I had said. I was pleasantly surprised that I had said nothing that I regretted, and many things I still agree with. The interview focuses essentially on three things: my activist roots, and the relationship between activism and historical writing; my understanding of the political conjuncture we were living through in the late 1980s; and the relevance of the ‘social constructionist’ approach to history that I had willy-nilly become identified with. The three aspects were of course inextricably linked. I spoke of the explosive impact of gay liberation on myself and many of my generation, which had not only changed my personal life, and political commitments, but also my intellectual interests and ultimately my career. When I first got involved in gay politics I was doggedly and haphazardly trying to complete a thesis in the history of political theory. As soon as I could, I happily and rapidly shifted to the more congenial, if then highly marginal and risky, territory of the history of sexual, and especially gay identities, sexual regulation, and sexual theory, the themes of my first three solo authored books. Because I found it virtually impossible to get a job in a university history department with books with titles like Coming Out, I reinvented myself as a sociologist (or at least a historically minded sociologist, or a sociologically inclined historian – in any case I ended up as a Professor of Sociology). I was moved along this path by my friendship and collaborations with Mary McIntosh and Ken Plummer, whom I first met through gay liberation meetings. These two, long before I encountered the work of Michel Foucault, inspired my efforts to develop to what became known as a constructionist approach to sexual history, which to my mind at least was no more than a properly historical approach to the understanding of sexuality.

When I did the interview in 1988 I was in a sort of career limbo. University teaching jobs were few and far between. Short-term research jobs like the ones I had had were drying up. And in any case, I was fed up with the insecurity and uncertainties of contract work. I took a job outside universities as an educational administrator. My pontifications in Boston were from this unlikely base. I was rescued eventually by the unexpected consequences of the crisis my friends and I were living though and trying to understand. The AIDS epidemic suddenly made sex research, even historical sex research, respectable; legitimation through disaster as Dennis Altman once put it. By now I had a long list of publications, propelled in part by the constant need to prove myself at the end of each short-term contract, and looked good for a university’s publically measured research ratings. And that stint in academic administration had given me experience of running things and of the development of academic policy. I got my first professorship, and the rest if not History was certainly my history.

This potted (auto-)biography illustrates perhaps the messy, contingent, hazard-strewn path of someone attempting to combine activism and academia in a highly uncongenial cultural moment. For me, however, it points to a different conclusion. In re-reading what I said in 1988 about politics and history I can’t help thinking about the importance to me of having an open, exploratory, but consistent political and intellectual project. The issues I raised about how to develop a radical, post-Marxist politics are as relevant in our neo-liberal but post-Crash times as they seemed to me at the height of what the High Tory commentator Peregrine Worsthorne described as Thatcher’s ‘bourgeois triumphalism’ in the late 1980s. And my comments on what is involved in a flexible, ‘constructionist’ approach to sexual history strike me as positively modest in the wake of the over-heated controversies that have flourished since. Above all, I am struck by my commitment to understanding the forms of agency, though never in circumstances feely chosen, which have made possible the changes that were transforming the sexual world then, and continue to do so today. This, perhaps, is where my own personal and intellectual formation in the sexual politics of the 1970s, my sense of the vital need to understand the political and cultural moment in all its complexity, and my belief in sexuality as profoundly and inextricably historical finally come together.

Jeffrey Weeks is a Research Professor in the Weeks Centre for Social and Policy Studies at London South Bank University. Following teaching and research posts at the London School of Economics, Universities of Essex, Kent, Southampton and the West of England, he was appointed as Professor of Sociology at LSBU in 1994. Having written extensively about gay and lesbian history over the last four decades, his most recent books are The Languages of Sexuality (2011) and a fully revised 3rd edition of Sex, Politics and Society (2012). He is currently working on a book entitled What Is Sexual History? to be published by Polity Press in 2015/16.

Jeffrey Weeks is a Research Professor in the Weeks Centre for Social and Policy Studies at London South Bank University. Following teaching and research posts at the London School of Economics, Universities of Essex, Kent, Southampton and the West of England, he was appointed as Professor of Sociology at LSBU in 1994. Having written extensively about gay and lesbian history over the last four decades, his most recent books are The Languages of Sexuality (2011) and a fully revised 3rd edition of Sex, Politics and Society (2012). He is currently working on a book entitled What Is Sexual History? to be published by Polity Press in 2015/16.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com

Jeffrey Weeks’ concluding remark about the historical characteristics of sexuality is timely. Those contemporary campaigns, which use slogans such as ‘born that way’, prioritise the biological over the historical and undermine the importance of collective agency. Such slogans also encourage a neglect of awareness of ongoing historical circumstances. Progressive change does not come to a final resting place; we need historical debate to keep us informed about the changes in the wider world around us.