Interview by Nicole Pacino

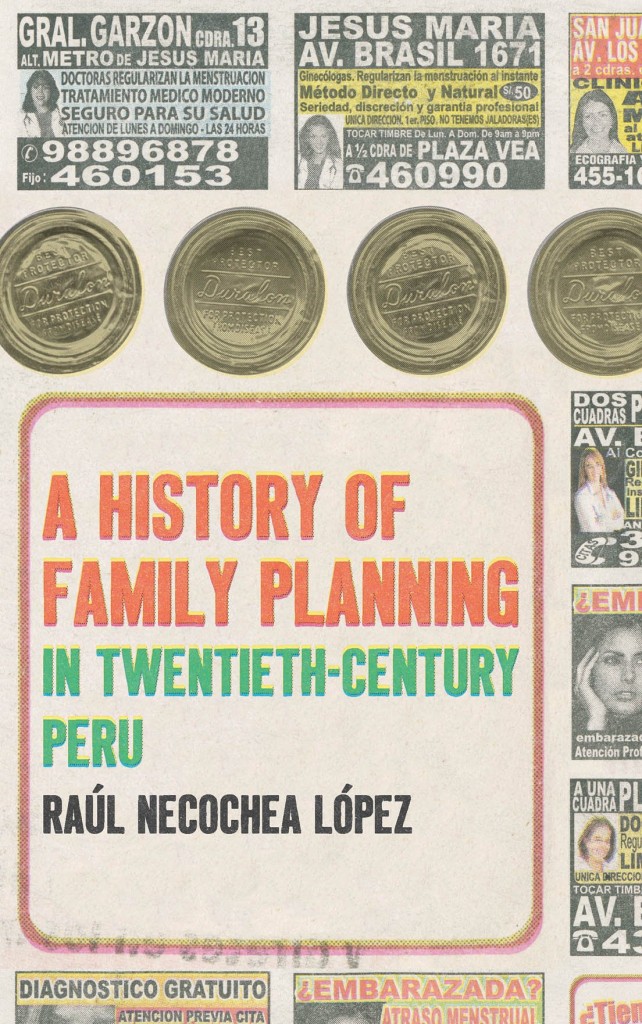

In A History of Family Planning in Twentieth Century Peru (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), Raúl Necochea López explores the changes and continuities in national conversations about fertility, family, and nation from the late nineteenth-century to the 1970s. Through chapters examining how divergent approaches to fertility control from the national government, the medical profession, moral reformers, and the Catholic Church intertwined at different points of the twentieth century, Necochea shows that family planning discussions were deeply integrated with conversations about national development and economic growth in twentieth-century Peru.

Drawing from an impressive selection of sources, including medical theses, government dispatches, newspapers, public health publications, personal interviews, and archival collections both in Peru and the United States, Necochea demonstrates that the personal ambitions, political ideologies, and religious affiliations of a multitude of local, national, and international actors shaped the trajectory of birth control usage and access during the twentieth century. In doing so, A History of Family Planning sheds light on topics such as contraceptive use and abortion that are underdeveloped in Latin American history.

Nicole Pacino: As you note in your introduction, we have so few histories that cover the topics of contraception, family planning, and abortion in Latin America. Why do you think this is the case? What sparked your interest in this research project in the first place?

Raúl Necochea López: We have good stuff on these topics, but much of it was written in the 1960s and 1970s, and not a lot was written by historians, as you say, but by policymakers or physicians. What these works have in common is a generalized concern with what was feeding rapid population growth, and how that growth allegedly got in the way of economic development. I suspect historians at the time might have been too close to the phenomenon of the mass consumption of birth control to be able to evaluate the momentousness of what they were living through.

On the other hand, I have the benefit of some 50 years of hindsight. I know family planning was tremendously significant and heavily contested throughout Latin America. That is one of the most important things that sparked my interest in this project. I also was trying to make sense of the forced sterilization scandal in Peru in the late 1990s, because it turns out that many of the arguments brandished about at that moment about the beneficence or wrongness of those state-sponsored programs were not entirely new. Unfair policymaking that affects sexual and reproductive behavior has deep roots in time. And yet, the more I dug, the more interesting other aspects of the story became. That is why the book ended up being not just about policymaking anymore.

NP: In the introduction you make the assertion that “we must pay more attention than we have so far to the U.S. experts who created the representations of 1960s Latin America as a demographic danger zone, as well as to their Latin American allies” (p. 9). What do you think we can learn from more research on these actors and their interactions?

RNL: When I speak of experts, I mean not only biomedical researchers and physicians, but also social scientists, industrialists, policymakers, and activists. These were the people who led initiatives and were most publicly visible. What I found was that they had strong ties to each other within the Americas.

This has made me more skeptical about the idea of family planning as something the US imposed unilaterally on Latin American experts. For one, not all US experts were on the same page about the relevance of family planning programs abroad. In addition, Latin American experts knew full well they were gatekeepers to resources, including political influence, patients, and the press, that could be leveraged to extract multiple benefits from their partners in the US, especially given the Cold War context that made rapid population growth an urgent issue to address.

NP: You cite a growing body of literature in Latin American history linking fertility and reproduction to discourses about civilization and modernization that posit that nation- and state-building is an explicitly gendered process. Chapters one and two, where governing elites agonized over the nation’s reproductive potential and the need to create “well-constituted families,” specifically engage this literature. What does this study contribute to discussions about state intervention in intimate matters like reproduction, breastfeeding, and child-raising?

RNL: For one, it shows how enduring the social roles of men, women, and families have been throughout the century, according to sociopolitical elites, but not only them. Despite the clear and longstanding evidence of female breadwinners and non-monogamous and non-nuclear families, we still act as if these things were unusual or inappropriate.

Another point the book raises has to do with the great concern elites displayed regarding men’s sexual and reproductive behavior early in the 20th century. The fear that men might corrupt their families, spread diseases, and not provide for their children was translated into different initiatives to “contain” their excesses and educate them. These were never tremendously widespread nor effective initiatives, but they existed, and they were all but forgotten after the mass marketing of modern contraceptives for women started.

NP: Abortion, which is the subject of chapter 3, is a very understudied topic in Latin American history even though we know it has been practiced in the region since well before Spanish colonization. One of the most interesting points about this chapter was that very few women or abortionists were ever prosecuted for what the state ostensibly viewed as a horrendous crime against the nation. What do you think this tells us about the state’s influence or control over its citizens, especially women and medical professionals?

RNL: Over the course of the century, the state’s ability to police the actions of women seeking abortions and abortion providers has been very limited. The brazen ads for interventions “to restore menstruation,” which you can still see throughout public urban spaces and even in newspapers are a symptom of that.

On the one hand, this gives the impression that women in 20th century Peru had little to fear from the establishment, despite the illegality of abortion in most cases. But it also means a wider supply market of abortion providers who benefited from the same leniency or lack of oversight, which translated into greater opportunities for abuse.

NP: Another of the book’s exciting contributions to historical scholarship is the subject of Catholic support for family planning initiatives, the focus of chapter 6. As you note, your research provides “an important revision of the portrayal of Catholic leaders as uniformly opposed to birth control” (p. 148). How do you think the Peruvian Catholic community’s advocacy of family planning methods compares with other predominantly Catholic countries, especially in Latin America?

RNL: You know, I am still holding out hope that one of these days some entrepreneurial researcher is going to find us evidence of other Catholic authorities justifying the use of family planning, pre- or post-Humanae Vitae. I have nothing but anecdotal evidence of priests and nuns elsewhere in Latin America invoking a person’s conscience as the highest source of authority regarding the use of contraceptives, but nothing yet like the organized and sophisticated approach of the Peruvian Catholic Church of the 1960s and 1970s.

It may well be they were exceptional historically, but their actions were not any big secret, and they were consistent with solid moral and theological reasoning. Moreover, ordained members of the Catholic Church in other Latin American countries knew about these actions, and most chose not to shun or denounce their Peruvian colleagues. Given the context, that’s pretty remarkable.

NP: One of the book’s strengths is your ability to weave together the different strategies and motivations of a variety of local, nation, and international actors regarding family planning activities. How did you decide on the book’s organization? Methodologically, what are the rewards of juxtaposing such a diverse array of perspectives, and what challenges did you face in creating your narrative and argument?

RNL: Organizing the book as a series of “vantage point” chapters was a relatively easy decision to make, after I took a look at the variety of materials I had gathered. Realizing that the diversity of representative points of view was a strength was something that many mentors and friends helped me see. It’s a flexible organizational framework as well. I mean, any future researchers might say, “look! You’ve missed this point of view.” And that would enrich the broth, so to speak.

Even after figuring out the structure of the book, though, I still needed a few guiding posts. I needed a theme that ran across the whole narrative. For the book, the way in which the control of fertility acquired such great public visibility in the 20th century, tying sexuality and reproduction to national economic development, was it. Boy, did it take me a long time to see that. Couldn’t see the forest for the trees, I guess.

NP: The book pulls from an impressive collection of interviews you conducted with physicians, midwives, family health educators, social workers, international health advocates, members of U.S.-based organizations, and the employees and volunteers of a variety of family planning organizations active in Peru between the 1930s and 1970s. Tell us about the process of conducting these interviews.

RNL: I really loved being able to do some interviews with people directly involved in the events I was documenting. As you say, the topic could make things tense, and I have written about one of my toughest interlocutors elsewhere. Another difficult part was finding the people I wanted to interview. That took quite a bit of detective work, luck, and connections. Even so, I have had a few doors slammed in my face, and a lot of phone calls never returned. Once, a woman accused me of pumping her for information so I could kidnap her adult son!

The interviews themselves have been, almost without fail, humbling and enlightening, and have helped me see sides of the story that documentary sources did not reveal. I don’t mean to romanticize interviewees, either. As with any other person, my rapport with some was easier than with others. In fact, I would not hesitate to call some of my interviewees friends now. On the other hand, it was hard to keep my composure when interviewing others. I especially remember an interview with a self-avowed racist, for example. That was no fun.

NP: Are there other groups or individuals that you were unable to include in the study that would have illuminated other facets of Peruvian family planning activities? If so, was this choice made on account of source material concerns or other factors?

RNL: As you have seen, I have little to say about how the first generation of users of modern birth control experienced these new technologies. Getting to that would have meant a tremendous investment in fieldwork, to identify interviewees, select them, conduct oral histories, and then analyze them. And then there’s the issue of my being a man talking mainly to women about their sexuality and reproductive behavior. I was reluctant to let go of that responsibility, say, to a female collaborator, but I was not sure how to best frame those conversations with me in the driver’s seat. In the meantime, the opportunity to publish the book came, and I decided to pursue it.

It still bugs me that we have such little understanding of that first generation of modern contraceptive users from the 1960s. The best we have, to date, are the KAP surveys conducted at the time, and those need some critical rejoinders using in-depth oral histories. If this sounds like I am throwing down the gauntlet for an entrepreneurial researcher to take up the challenge, it’s because it is.

Raúl Necochea López is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Medicine and an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. He is the author of A History of Family Planning in Twentieth Century Peru, published by the University of North Carolina Press.

Raúl Necochea López is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Medicine and an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. He is the author of A History of Family Planning in Twentieth Century Peru, published by the University of North Carolina Press.

Nicole Pacino is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. Nicole’s research focuses on the political uses of public health in the aftermath of Bolivia’s 1952 National Revolution. She has articles published in The Latin Americanist and the Journal of Women’s History, and is working on a book manuscript entitled Prescription for a Nation: Public Health in Post-Revolutionary Bolivia, 1952-1964.

Nicole Pacino is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. Nicole’s research focuses on the political uses of public health in the aftermath of Bolivia’s 1952 National Revolution. She has articles published in The Latin Americanist and the Journal of Women’s History, and is working on a book manuscript entitled Prescription for a Nation: Public Health in Post-Revolutionary Bolivia, 1952-1964.

NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.notchesblog.com.

For permission to publish any NOTCHES post in whole or in part please contact the editors at NotchesBlog@gmail.com